It got suddenly chilly in the second week of May, but the cold masks an underlying warming that has continued for over half a century. [8 June 2010 | Peter Boyer]

Global warming would have been the farthest thing from your mind if you’d spent a certain weekend last month at Liawenee on Tasmania’s Central Plateau.

The night of Saturday 22 May was Tasmania’s second-coldest May night on record — a frigid minus 10.2C. It just failed to beat the coldest — minus 10.5C at the same place on May 30, 2006.

Liawenee wasn’t alone in being cold last month, the Bureau of Meteorology reports. Overnight minimum temperatures were below average in most areas — by almost two degrees in the upper Derwent Valley and southern Midlands. The May average minimum temperature for Dover was the lowest in the 20 years of records there, and Bushy Park and Swansea had their lowest since 1979.

These extra cold nights have happened at a time when global warming continues to dominate discussion in scientific circles. If you’re puzzled about this, Tasmania’s longer-term weather records may help sort out the dilemma.

It’s all a matter of finding patterns in confusing data, or “noise”. At any time in any year, regional weather patterns can cause conditions to jump to extremes, apparently discounting background influences like greenhouse warming. Making sense of such anomalies is the job of people like Ian Barnes-Keoghan, the Bureau’s climatologist for Tasmania and Antarctica.

In his latest monthly report, Mr Barnes-Keoghan noted that May was on track to be much warmer than normal — with some centres recording maximum temperatures over 20C — until 11 days in, when the sudden arrival of cold conditions changed everything.

By the end of May, what had started out as another warm month turned out to be close to average. Minimum temperatures were slightly below average in the south-east and average or slightly above elsewhere, while maximums were at or slightly above average everywhere.

All this might lead us to think that Tasmanian temperatures are pretty much as they’ve always been, but that would be a hasty conclusion. Digging deeper into the data shows a clear trend: Tasmania is warming, just like the rest of Australia and most other parts of the world.

Mr Barnes-Keoghan’s report for autumn 2010 reveals unusually mild temperatures for all but the last part of May, with many Tasmanian sites having their warmest autumn for many years. A few centres had their highest autumn mean temperature on record — including Hobart, where comparable observations extend back to 1896.

Daytime autumn temperatures were especially high. In south-eastern Tasmania, east of a line running from about Scamanda to the far South-West and including Hobart, the maximum temperature average was the highest on record, while everywhere else, including the Bass Strait islands, they were well above average.

To top it all off, the year from June 2009 to May 2010 was Tasmania’s second-warmest 12-month period on record (surpassed only by the period May 2009–April 2010).

Australia as a whole experienced a warmer-than-usual autumn, with both maximum and minimum temperatures above average. Like Tasmania, Western Australia was exceptionally warm. Autumn in South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales was warmer than normal, while it was slightly cooler than normal in Queensland and the Northern Territory.

The Bureau of Meteorology has established a “high quality climate site network”, for which it has identified strategically-located observation sites around the country, including six in Tasmania, able to provide reliable long-term data sets which it uses to track climate trends around the country.

Some of these data sets have been influenced by the impact of a growing population around the site in question — the human warming influence known as the urban heat island effect. In such cases the data sets are adjusted by incorporating information from nearby sites unaffected by human activity.

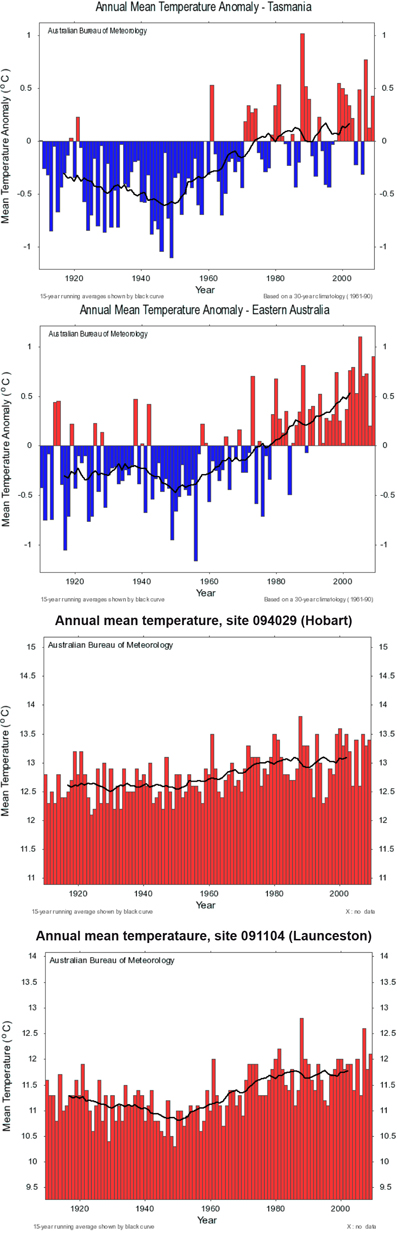

Temperature data for the six Tasmanian sites — Hobart, Launceston, Cape Bruny, Strahan, Wynyard Airport and King Island Airport — can be observed on the Bureau’s website as a graph extending back as far as 1910 (a few years later for King Island and Cape Bruny).

While the temperature trend is less pronounced for Hobart and Strahan, the data for every one of the six sites shows a definite warming trend since about the middle of last century.

In the case of Hobart, the mean temperature trend line tracks from around 12.6C around 1950 to over 13C currently, while the Launceston mean trends from about 11C around 1950 to about 11.7C now.

A broader-scale data set shows that while Tasmania’s overall temperature changes have been more moderate than for eastern Australia as a whole, they also follow a clear warming path.

Since the mid-20th century Tasmania’s average annual mean temperature has trended up by over 0.5C. For all eastern States (including Tasmania), the upward trajectory is much more pronounced, by nearly a full degree.

Recent years have shown that the battle over global warming has a heating effect independent of the climate. The Bureau of Meteorology’s work to identify patterns beneath the noise of daily data is a welcome cooling breeze.