Franklin Roosevelt’s advice to his people to get together and start doing things is being applied by local governments in preparing for future oil scarcity [12 July 2011 | Peter Boyer]

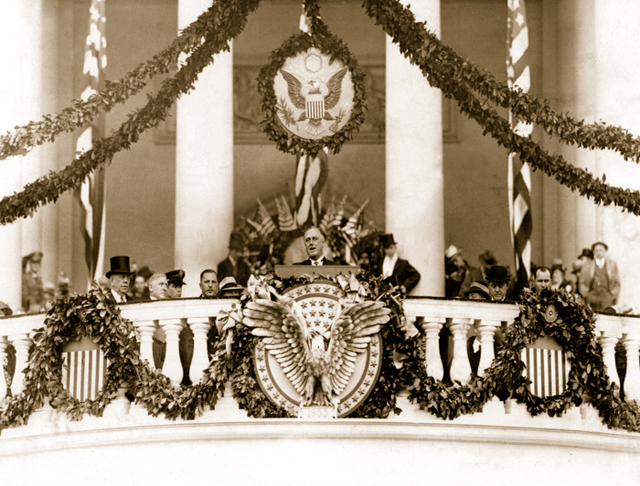

“...the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”—Franklin Roosevelt addresses the American people at his inauguration. PHOTO NEW YORK TIMES

It’s hard to imagine a bleaker outlook than what Americans were facing on 4 March 1933, their new President’s Inauguration Day.

The temperature in Washington on that damp, gloomy day reached a little above 5C. The grip of the Great Depression was tightening, with US unemployment at 20 per cent and climbing sharply. Four months earlier, the nation had elected a cripple as its 32nd President.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, disabled by polio a decade earlier, had to rely on braces as he stood erect before a microphone in front of a large, hushed crowd, and declared that it was time to “speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly.”

With his words beamed out to millions of Americans via the new miracle of radio, Roosevelt sought to confront the pervading sense of gloom by defining the enemy: “Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror.”

This was a different enemy. Not something from outside, clamouring at the city gates, but a deep anxiety lurking within each person in that country, and by extension in the rest of the world, since the Depression’s poverty and hardship were felt virtually everywhere.

Economic depressions were nothing new, but this one was unprecedented in its global reach, leaving no advanced country untouched and offering no wealthy neighbour to come to the rescue. When Roosevelt took over as President, it seemed that it would never end.

The solution lay with the people at large, who needed to come together and work “as a trained and loyal army”. Roosevelt pledged that if the crisis demanded it, he would ask Congress for the power “to wage a war against the emergency, as if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

The Great Depression continued for another decade, well into World War II, but the hard times became more bearable as the 1930s rolled on. Whatever the cause of the economic recovery, it’s widely agreed that Roosevelt’s grasp of the Depression’s psychological dimensions was a key.

Like all strong democratic leaders, Roosevelt understood the crucial role of people’s inner feelings in dealing with crisis. He knew that the antidote to personal anxiety was combining with others and doing things together.

It was with that understanding that a group of Tasmanians organised a public forum early this month to share information about progress here and interstate in preparing for the impact of global peak oil.

Peak oil and climate change are two sides of the same coin; both are an unfortunate consequence of us burning around five billion tonnes of oil around the world each year (nearly a million tonnes in Tasmania alone). For both reasons we somehow have to find a way to live with less of it.

A few months ago the chief executive of the International Energy Agency, Dr Fatih Birol, finally confirmed what world governments had long suspected but refused to discuss openly: that the world passed the peak of oil production some five years ago, in 2006.

Like Roosevelt’s New Deal, the aim of Peak Oil Tasmania, the organising group for the Hobart forum, was to encourage Tasmanians to learn from others’ example the positive benefit of acting together to mitigate the impact of oil scarcity.

This was the second Peak Oil Tasmania forum, but unlike its predecessor its list of presenters included people working in or with local government specifically to work out how a shortage of oil might affect communities, and what could be done to prepare for it.

Rod May, mayor of Victoria’s Hepburn Shire, which operates Australia’s first community-owned wind farm, spoke about the practicalities of developing Australia’s first “energy descent action plan”, in which the shire is preparing itself for an oil-constrained future.

His council’s “can-do” approach to sustainability programs was supported by Huon Alderman Liz Smith, whose take-away message from the national Sustainable Councils Conference last month was that councils need to think long-term and work with their communities to manage transition.

Hobart Alderman Philip Cocker, who led a successful push to have Hobart City Council examine the impact of peak oil on the city, urged a greater focus on future fuel scarcity by Tasmanian councils and a coordinated approach to operations affected by it.

While local government didn’t rate at the previous Hobart peak oil forum, Hobart’s Lord Mayor, Alderman Rob Valentine, and Alderman Damon Thomas, a declared mayoral candidate to succeed Valentine, were present for all or part of this year’s discussions.

This is progress, but the absence of any state or federal politician from the forum was a reminder that peak oil doesn’t yet rate as a political issue. It’s to be hoped its profile gets a lift when the State Government releases the findings of its current oil price vulnerability study.

Franklin Roosevelt had something to say about living with less. Happiness, he told his Inauguration Day crowd, “lies not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort”. Amen to that.

• Click here for more information about the “Peak Oil and You” forum.