Climate Futures for Tasmania was a far-sighted investment in a unique product that will be an invaluable tool for land managers in the 21st century. [11 October 2011 | Peter Boyer]

Here’s some good news. The Tasmanian government, for all its financial woes, has made a long-term investment that the wise money says will pay for itself hundreds of times over.

Here’s some good news. The Tasmanian government, for all its financial woes, has made a long-term investment that the wise money says will pay for itself hundreds of times over.

In 2007 the Lennon government entered a visionary agreement involving eight government departments (four Tasmanian, four Commonwealth), the University of Tasmania, the CSIRO, Hydro Tasmania, the Tasmanian Institute for Agricultural Research, the Tasmanian Partnership for Advanced Computing and the Antarctic Climate and Ecosystems CRC (ACE-CRC).

The agreement, which came on the back of an innovative 2001-04 Hydro Tasmania project to model future climate out to 2040, aimed to build a comprehensive picture of how our climate will change over the next century, and to do it at a level of detail that leads the world.

The research group Climate Futures for Tasmania (CFT) seems to have done just this. To Climate Commissioner Professor Will Steffen, its achievement is unique: “There’s nothing else like it,” he told Climate Change Minister Cassy O’Connor when he visited Hobart in August.

CFT’s success rests in part on the global reputation of climate modeller Professor Nathan Bindoff and the exceptional scientific and computing talent he was able to bring together at the ACE-CRC.

The group achieved a resolution in its models unmatched anywhere on the planet, “dynamically downscaled” from global model grid squares 200 km across down to 10 km squares, allowing it to factor in the impact on climate and weather of local topographical features.

Its success also depends on the quality of the group’s peer-reviewed reports that came out in stages over the past year or so, on general climate impacts, modelling methodology, agricultural impacts, water and catchments, and the last one, released last week, on extreme weather events.

A third big reason for its success has been CFT’s consultation with farm managers, agricultural organisations, local government and other regional interests across Tasmania to ensure its output would be of practical value to those with most to lose from an unstable, unpredictable climate.

The final CFT report provides policy-makers, infrastructure managers and Tasmanians generally with a description of extreme weather ahead that’s unprecedented in its detail and resolution.

There’s good news for heat-seekers. If you like your summers warm and long with tropical nights (minimum temperatures above 20C), you’ll be pleased to know that Tasmania is going to get many more warm summer days and nights as the century progresses.

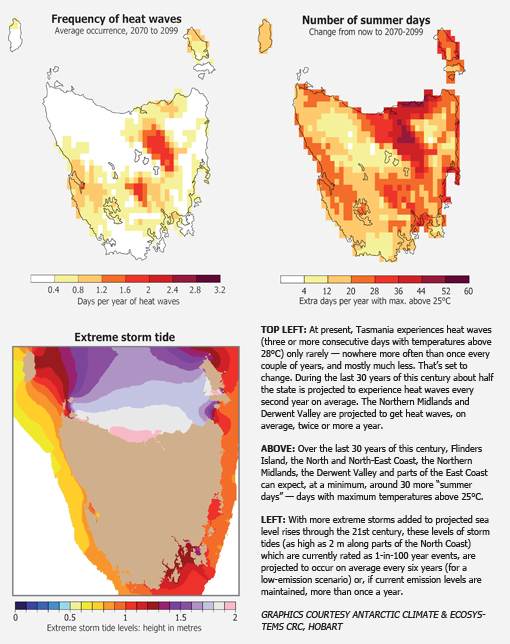

By 2100, the report says, most of Tasmania will get around three times as many days with a maximum above 25C. In winter we’ll get fewer cold spells and fewer frosty mornings.

Sweltering nights don’t happen in Tasmania, or so we’ve always thought. But by 2100 we can expect to get quite a few every summer. Along the north coast and on Flinders Island, CFT calculates that every year, on average, we’ll get as many as 20 nights above 25C.

Here’s a sample of what else we can expect as the century wears on:

• Warm days and warm spells will be especially prevalent in the central north and midlands, the Derwent Valley and the west coast around Macquarie Harbour.

• Extreme rainfall events will become more intense, consistent with a warmer climate, mixed together with more dry days. Extreme wet days will increase in the southwest and northeast, while the central highlands will get fewer extreme wet days in all seasons. Drying will be most pronounced in the northwest.

• Recurrence intervals between extreme rainfall events are likely to decrease substantially. In some places, an event so extreme that we can currently anticipate it only once in 200 years will happen every 20 years.

• River flows will fluctuate more, with severe flooding events likely to increase significantly in most major river basins through the 21st century.

• With more extreme storms added to a projected sea level rise of up to 14 cm over the next 20 years, the incidence of storm tides and surges that we currently rate as 1-in-100 years will by 2030 be doubled, to 1-in-50 years, and will be increasingly frequent as the century progresses. The most vulnerable coasts are in the southeast and those facing Bass Strait.

New modelling and analysis techniques produced an understanding of the regional wind hazard across Tasmania at a level of detail not previously possible. The information has been utilised for a web-based tool to guide emergency services in determining where and how to adapt to future wind hazard and risk.

Local government can make direct use of the research by utilising “Climate-Asyst”, a tool developed using CFT data by Tasmanian consultants Pitt & Sherry.

There’s one other benefit of the CFT research. For the first time, Tasmanians can read descriptions of the physical outcomes of a warming climate where they understand it best — in their local area.

Nowhere else in the world is such a detailed picture yet possible. I suspect that the team members who are now looking for work won’t have long to wait.

They may as a result have to relocate interstate or overseas. After all they’ve done and might continue to do for this island, that seems a shame. But we can’t hide such talent, and heaven knows the world needs them.

• You can find all the Climate Futures for Tasmania reports on the Department of Premier & Cabinet website.