Our first priority in finding a sustainable pathway is to attend to our neglected public space. [2 October 2012 | Peter Boyer]

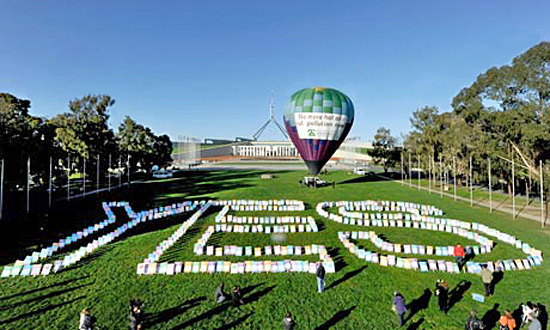

Citizens come to the lawns of Parliament House, Canberra, to support the carbon tax, October 2011. PHOTO ALAN PORRITT/AFP

Confidence is everything. It can make an apparently hopeless cause seem possible and transform what seems a threatening obstacle into an opportunity, a spur to action.

Sometimes the goals of stopping our greenhouse emissions, adapting to a changing climate and bringing energy needs down to sustainable levels look like a towering range of unscaled mountains, with storms, earthquakes and avalanches thrown in.

So much to do, so little time. So many trends to reverse, minds to change, miracles to achieve. It’s hard to feel confident in the face of such odds.

Real confidence — the kind that isn’t defeated by the first setback — isn’t easy to come by. It involves hard thinking and hard work.

If we want to meet and beat the challenges of tough times, we need to know what we’re capable of and have a solid grasp of the task at hand, and that means getting our priorities right.

“Are we having the right conversations about sustainability?” was the question posed in a session of the Tasmanian Leaders Program in Hobart 10 days ago, in which I and three other panellists fronted 24 strongly-engaged members of Class of 2012.

An architect discussed how better knowledge and materials were raising the bar on buildings’ energy efficiency, and an evolutionary biologist spoke of humans’ inherited tendency to ignore problems with a long time frame, posing real difficulties for securing effective action.

A geographer urged aspiring leaders to take personal responsibility for doing what was necessary to improve sustainability, but also to take heart from the great capacity of people to find imaginative and effective solutions when pressed.

My take on the question was that in our battle to build sustainable communities we have to look to ourselves. Despite our astonishing capacity to come up with technical answers to every conceivable need, the real test is how humans respond, or don’t respond, to this great challenge.

A crucial factor in play here is how government and big business relate to each other, and it’s throwing up huge questions as we struggle to find clear pathways to sustainability.

This has history, as old as human society itself. Once, government and business were inseparable partners in power, but the scene changed with the rise of modern democracy, which opened up a gap between elected, accountable governments and unelected private corporations.

With democracy came public debate, as differing ideologies and interests competed for the right to govern or influence government. After World War II, it seemed for a while that we were heading into an era in which the general public and its shared resources, the commons, were ascendant.

But Australia and the rest of the developed world have since seen a massive power shift. The ideology of the free market drove a lifting of restraints on corporations’ ability to operate across national borders, enabling them (to their great benefit) to play governments off against each other.

The resulting exponential growth in the global economy made millions for many, fuelling further deregulation of global business, until the bubble burst in 2008. But the financial crash was a small price to pay compared to a much greater loss that will be harder to redeem.

That loss has been the sad neglect of our public space, the modern equivalent of the Roman Forum, in which genuine public interest should expect to win the day. It has cast doubt on our capacity to work together — government, business and the rest of us — to develop sustainable practices and infrastructures.

This isn’t to say that Australians are no longer engaged with public issues. Technologies such as the web, email, Facebook and Twitter have greatly increased our capacity to make and retain contact with others.

As we’ve all seen, you can use these technologies to “talk” to many others, to inform people and get them together to protest or celebrate. All strength to them insofar as they assist a functioning democracy.

But their existence is no proof that all’s rosy in the democracy garden. At best they’re a partial antidote to the sheer economic and financial muscle of big business.

In 2009 I spent time in Canberra on behalf of the Australian Conservation Foundation lobbying MPs for stronger emission control measures. One of these told my group that of “hundreds” of approaches he’d had on this issue, ours was the first arguing in favour of such measures. Fossil fuel and related business interests accounted for the rest.

It was a sobering reminder of what we were up against. We should never assume that democracy can’t be bought off by private interests, or that rational argument in the interest of the general public and the global commons will necessarily win the day.

Equally, we should never give up. We have no other option; this is too important a cause. A stronger engagement in the public debate about how we shape our future will be crucial in developing our confidence, which as we know is essential to achieving good outcomes.

The success or otherwise of ordinary Australians in occupying, defending and bolstering the public realm will determine how we fare in the critical battle for a sustainable economy. It’s that simple.