Our response to climate change is not keeping pace with actual changes, but the Paris meeting leaves room for a smidgin of hope. [Peter Boyer]

Greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere and the temperature at its surface were both at record levels in 2015. Here’s our response.

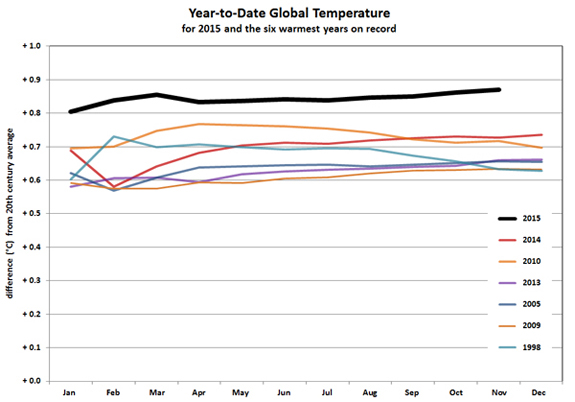

NOAA’s graph showing year-to-date data for 2015 (black line) against current warmest years on record.

JANUARY: The world’s rich and powerful assembled at Davos were told of accelerating danger from carbon emissions, declining food resources, deforestation and fertiliser pollution. Some hand-wringing aside, no response was recorded.

FEBRUARY: After confirmation that 2014 was the warmest year on record, a US geologist told a Hobart audience that warming in the past 20 years has been 15 times faster, and carbon dioxide levels have risen over 300 times faster, than when we came out of the last ice age.

The Hodgman government’s energy strategy acknowledged the potential value to the Tasmanian electricity system of rooftop solar, electric cars and battery power.

MARCH: Treasurer Joe Hockey’s intergenerational report made no mention of the climate, while Tony Abbott told parliament that his government’s effort to curb emissions was “absolutely amongst the best in the world”. Tasmania put a five-year ban on natural gas fracking.

APRIL: While cutting science and education funding, the Abbott government announced that it would spend $4m to bring to Australia the climate revisionist think-tank of Danish political scientist Bjorn Lomborg. When universities objected it dropped the idea.

Environment minister Greg Hunt announced the “stunning” success of the first publicly-funded “reverse auction” to buy abatement. Growing trees and managing landfill got funding, but the big polluters – mining, metallurgy and energy industries – were notably absent.

JUNE: In his environment encyclical, Pope Francis recast the climate debate by declaring life on earth to be endangered by human excesses, including the burning of fossil fuels, and called for swift and decisive action to limit the damage.

Who says Australia can’t be a climate leader? Having already become the first country to abolish carbon pricing, it also was first to scale back a climate target, cutting by 20 per cent cut the amount of large-scale clean energy it aims to have in 2020.

The Abbott government also announced it would no longer allow the Clean Energy Finance Corporation to fund wind and photo-voltaic solar projects, while floating the idea of a commission to investigate complaints about wind turbine noise.

JULY: Pitt & Sherry’s CEDEX report showed emissions from burning coal for electricity had risen to where they were in mid-2012 when carbon pricing began.

AUGUST: The Abbott government announced Australia’s 2030 emissions targets (26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels), rebuffing criticism that they were weaker than those of New Zealand, the US, Canada and Europe.

A strong case for government support of electric car take-up was put to energy minister Matthew Groom when he launched a Tasmanian branch of the Australian Electric Vehicle Association. He said he preferred to see change determined by the market.

SEPTEMBER: Soon after the Tasmanian Liberal conference voted against cutting emissions to focus on adaptation, the Abbott cabinet signed off on a new “safeguard mechanism” to keep big carbon emitters in check. It was immediately attacked for allowing polluters too much leeway.

The mid-month defeat of Tony Abbott by Malcolm Turnbull raised hopes for stronger climate policies. But Turnbull declared our emissions targets were adequate and described the clearly inadequate Emissions Reduction Fund as “a very, very good piece of work”.

OCTOBER: Questions about the Turnbull government’s climate policy continued as it appointed a commissioner to study any deleterious effects from wind-farm sound.

Turnbull declared support for a long-term coal industry just before Hunt approved the Carmichael coal project in Queensland. Both were flying in the face of scientific advice that a safe climate means leaving most known fossil fuel reserves untouched.

NOVEMBER: The Turnbull government lifted restrictions on the operation of clean energy agencies, and on the last day of the month Turnbull joined other world leaders at the UN climate conference in Paris.

DECEMBER: Over 40,000 people gathered in Paris for the UN climate meeting, possibly the largest assembly of people for any conference, ever. While scientists were generally disappointed at the outcome, politicians, diplomats, business people and others rated it an outstanding success.

Just after the release of a promising Tasmanian climate strategy, and with hydro dams less than a quarter full, the Basslink connection to the national electricity grid went down, creating a crisis for Tasmanian power generation and sparking calls for a second Bass Strait cable.

The year had its share of technological success. An aircraft powered by the sun, Solar Impulse 2, flew halfway round the world, and US-based entrepreneur Elon Musk started up a battery “gigafactory” to supply affordable power storage to homes.

Finally, data released a fortnight ago by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed 2015 temperatures tracking much higher than in record-breaking 2014 – solid evidence that the climate crisis is not some way off in the distant future, but happening now.

It’s not hard to conclude that 2015 has been another wasted year, and that political leaders who support fossil fuel use while claiming abatement success are having their cake while eating it too. But things are more complicated than that.

Fossil fuels and our lifestyles are like conjoined twins. Separating them demands focused, sustained, economical effort with clear physical effect on a global scale. Politics and diplomacy are entirely unsuited to such a purpose, but they’re all we’ve got.

At the Paris meeting the world’s governments accepted that existing measures are failing and signed up to do better, year on year, into the indefinite future. If we can hold them just to that, we still have a glimmer of hope.