We have learned a great deal since February 1967, but that doesn’t include how to curb our damaging carbon emissions.

Dr Jim Marwood took this photograph of the remains of Fern Tree Hotel on the afternoon of 7 February 1967.

This has been as near to perfect a Tasmanian summer as I can imagine. Rain when you need it but not too much, and just enough sun and wind. Not hot enough for some, but hot enough for me.

That wasn’t the case in early 1967. After a good spring, the rain stopped altogether and the heat came down from mainland Australia. I wasn’t bothered because I was young. But then, exactly 50 years ago today, the wind came, and we lost our youth.

The fires that devastated southern Tasmania that day are seared into the memories of all who experienced them. For some the memories were traumatic, and for some they remain so.

Over summer I’ve been privileged to be part of a group putting together an exhibit about the Fern Tree community’s 1967 fire experience, in the course of which people who were on the mountain that day recounted their stories of terror and courage and blind luck, good and bad.

Dominating the Fern Tree story is the experience of fire refugees who, early in the afternoon of Black Tuesday, gathered at the community’s only open space, in front of the Fern Tree Hotel, a large two-storey timber structure that had stood for 65 years.

As fire closed in on all sides and smoke turned day into night, some 200 people prepared to die. They all survived because a wind change allowed rescue trucks to carry them away from the burning hotel in a terrifying, unforgettable journey through burning bush to Hobart.

Working in the Mercury’s Macquarie Street building that afternoon, I had no such experience. It was only in stages, over that evening and the days following, that I realised the scale of devastation, including the death of my father’s sister as her Derwent Valley farmhouse burned around her.

We have since found out much more. Roger Wettenhall’s 1975 book, Bushfire Disaster, revealed losses worth $40 million (nearly $1 billion today), including over 1300 homes. Most shocking, there were many deaths; recent studies have brought the number killed to 64.

An important trigger for this disaster was over 100 fires burning that morning in southern Tasmania, including in the hills behind Hobart – far beyond the capacity of the available 200-odd men and 20 vehicles to extinguish even in still conditions.

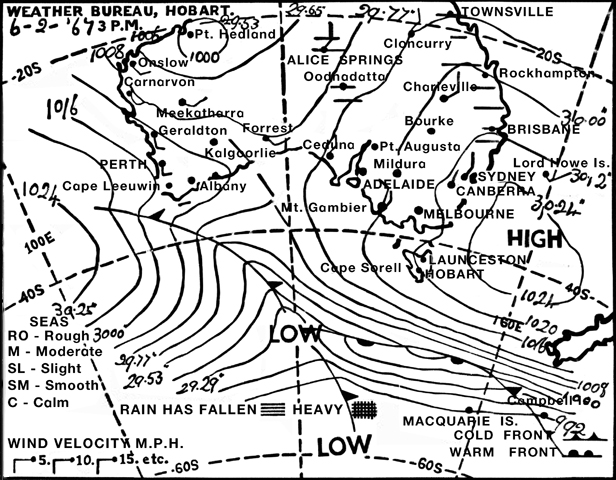

Add to that the state of nature. Dry bush was made all the more flammable by a hot northerly airstream caused by a stationary high-pressure system over the Tasman Sea. That was predicted the previous day by the Bureau of Meteorology, which warned of “high to extreme” fire danger.

The map issued by the Hobart Weather Bureau the day before the 1967 fires showed barely a hint of the devastating weather to come.

But the official forecast overlooked the potential impact of a low-pressure system forming on a front to the south-west. That brought much stronger winds than forecast and much hotter conditions – a Hobart maximum of 103 degrees Fahrenheit (39C), well above the forecast 88F (31C).

To this day, Tasmania’s highly-variable weather remains hard to predict. Just last Monday, BOM’s forecast included high winds and high fire danger caused by an approaching cold front. Winds and temperature that day turned out to be moderate, accompanied by a little rain.

But whereas the forecast for Black Tuesday 1967 missed some danger signs, last Monday’s did not. BOM is well aware that if a fire weather forecast is in error, better that it be on the side of caution.

In 1967 computers and satellites were just beginning to be used as forecasting tools, and forecasts for Tasmania had to make do with just 20-odd observations across the entire Southern Ocean. Today they draw on thousands of automated observations over land and sea.

The result is that forecasting accuracy has increased many times – very high for one or two days ahead with a reasonable chance of getting it right a week ahead. That alone gives today’s fire and emergency services a distinct edge over their 1967 predecessors.

Fire-fighting capacity state-wide has increased tenfold, from 500 men using about 45 appliances and 23 separate, very flaky command and control systems to over 5000 fire-fighters (male and female) using over 450 appliances and a single, far more reliable control platform.

This is comforting, but Victoria’s 2009 disaster and Dunalley’s experience four years ago show the futility of imagining we can control nature. Climate change is bringing longer summers, hotter days and wilder winds. Devastating bushfire will figure in our future as well as our past.

Fire services understand that, because they see it happening year on year. They are now more prepared than they’ve ever been to fight it, but without a concerted local, national and global effort to curb greenhouse emissions, the battle will be a losing one.

• Fern Tree Under Fire, a display about Black Tuesday on Mt Wellington (Fern Tree Community Centre, 8 Stephenson Place) has its final day today, opening from 10 am to 6 pm. Entry is free.