Clear-felling of mature native forest and burning the residue is a seriously carbon-intensive activity, according to a strong body of scientific evidence. Changing this practice to conserve such forests can bring economic reward. [29 April 2008 | Peter Boyer]

A pall has descended over Tasmanian forestry. It’s there in the smoke that drifted over town and country last week. But it’s another kind of pall too – a gloom of uncertainty about where we go from here.

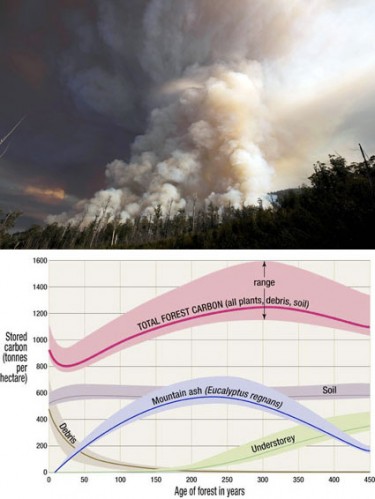

TOP This smoke plume, from a 100-hectare coupe in the Weld Valley about 10 days ago, carried about 20,000 tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, based on Forestry Tasmania research on carbon lost in regeneration burning at a site close by in 2001. BOTTOM This ANU graph by forest scientist Christopher Dean and others shows how carbon accumulates in a mature Eucalyptus regnans forest, reaching its peak, between 1100 and 1600 tonnes of carbon per hectare, after around 300 years. Less than half is taken for pulpwood or sawlog, and of that, less than five per cent of the carbon ends up in durable wood products. After a burn-off, only tree roots and some soil carbon remains. The rest is up in the air.

The uncertainty will only increase as long as politicians, bureaucrats, business leaders and conservation groups continue to pursue political points at the expense of preparing our forests, and us, for a whole new future.

Much of the problem is very visible every autumn, in the inferno of a regeneration burn-off, or “regen burn” – done to scour the land so that eucalypt seeds can get direct access to mineral soil, which they need to germinate.

But there’s an important third element, far removed from the battles and burn-offs in our forests. It’s a game called international diplomacy, played by national leaders – and in that game, the big loser has been truth.

When the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in 1997, Australia won a generous emissions target by bargaining hard to include a reduced rate of land clearing as a factor in the final agreement. It achieved this by making sure forestry was excluded from the deal.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, clear-felling mature native forests to grow new trees doesn’t count as land-clearing, so carbon emitted from that activity is left out of the ledger. The result is that forestry gets a dream run in official emissions statistics.

•••

For 10 years our forestry industry has argued that its activities are greenhouse-friendly and that all the new trees planted make it possible to continue a slash-and-burn regime in our mature native forests.

But estimates using scientific findings and Forestry Tasmania’s own data put native forest logging in the front rank of Tasmanian carbon polluters.

In a Hobart public forum last week, forestry industry representatives presented as “fact” official graphs prepared under Kyoto accounting rules that wrongly show forestry as greenhouse-friendly – a net absorber of carbon dioxide.

It’s possible they sincerely believed this. But even if the truth is known to some in the industry, it would be very difficult to raise it publicly because of its ramifications. The solution will mean permanent changes to the industry as we now know it.

•••

In putting this information together, I’ve tried to keep my distance from the Tasmanian forestry debate. While I once worked for Forestry Tasmania, that employment ended long ago. I have never taken part in any forestry protest, nor joined any conservation organisation.

My only concern here is climate change. If an activity is benign, if it doesn’t contribute to greenhouse pollution, I ignore it. But the evidence says that forestry as it’s practised in Tasmania today is anything but benign.

The forest conflict makes it a tortuous business to get access to good, solid scientific data. Hostility breeds polemic – never a reliable information source – and that compromises both conservation activists and forest authorities. Credibility is further compromised by the commercial imperative driving our forest industry.

But some serious research on how carbon is acquired and stored by forests is being done in plant science departments of universities, notably the Australian National University, along with greenhouse accounting and bushfire CRCs.

I’ve learned that in assessing carbon in forests we need to look at two things: capture and storage. There’s no doubt that young, quickly growing trees are better at capturing atmospheric carbon than older trees. So, we replace the old trees with young ones – right?

No. Not a good idea, it seems, because of carbon storage. Perfectly adapted by evolution to their environments, mature forests have been accumulating carbon for centuries in canopy species; understorey plants (including trees, shrubs, ferns and mosses); debris, peats and soils.

A mature wet eucalypt forest in Tasmania has been estimated to contain between 1100 and 1600 tonnes of carbon per hectare – a level which regrowth forest takes centuries to reach. Plantations, whose life is measured in decades, store less than 10 per cent of this amount.

The evidence says that clear-fell logging in any mature native forest results in a loss of carbon that it will take hundreds of years to recover.

•••

Only the most intense wildfires are comparable with eucalypt regeneration burn-offs. Normal wildfires and controlled fuel-reduction burns eliminate lower-level plants and sometimes destroy the big canopy trees.

But “regen-burns” are designed to be intensely hot. The result, as a forestry colleague of mine put it when I worked in the industry, is like a nuclear explosion. Nearly all combustible material is sucked into the air in a massive blast, leaving behind (as intended) bare earth.

The billowing smoke from “regen-burns” in Tasmania’s mature forest sends vast quantities of carbon into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

A 2001 Forestry Tasmania study estimated that the amount of carbon in the smoke of a wet eucalypt regeneration burn averaged 196 tonnes per hectare. This would mean the smoke from a 100-hectare coupe contains 19,600 tonnes of carbon.

We need more data on the combustion process and what happens in other forest types, but with ANU research showing such forests contain well over 1000 tonnes per hectare, the Forestry Tasmania estimate seems conservative.

But using this official data and making allowances for lower output from drier forests, CO2 emitted from regeneration burning alone is at least on a rough par with the state’s total transport emissions.

Time is against Forestry Tasmania’s long-term plans, which show forest operations will be net emitters of carbon each year until 2026, when growing forests will take up more than is given off.

Even if that’s true, it will be nearly 20 years too late for our 2050 emissions target. Savings in 20 years’ time are worthless if in the meantime we have maintained high-polluting regimes. Every delay makes future action that much tougher.

Leaving logging out of carbon emission estimates is self-defeating. Australia must account for all polluting in its internal accounting systems – now, not after the Kyoto period ends in 2012.

•••

Premier Lennon has asked Professor Ross Garnaut, who is investigating economic aspects of climate change, to look at the impact of logging. On the evidence I saw, Garnaut would conclude that today’s mature native forest logging regimes are dangerous and recommend they be stopped.

But rural communities have reason for optimism – and politics will play a part in this.

Tasmania will have a legislated 2050 emissions target that’s 60 per cent below 1990 levels. At present, our electricity consumption, increasingly reliant on Victorian coal-fired power via Basslink, is taking us in the opposite direction.

But with clear-felling and regeneration burning stopped, Tasmanian carbon emissions would be sufficiently below historical levels (adjusted to take account of forestry’s real impact) to meet most of what will otherwise be a near-impossible 2050 emissions reduction target.

Soon, all carbon emissions will cost money. The economic value of such emission reduction would far exceed the return from harvesting wood fibre, enough to sustain rural communities while they manage and conserve these great carbon stores in perpetuity.

Conversely, continuing such clear-fell regimes with their attendant emissions would impose heavy financial costs – almost certainly enough to make them uneconomical.

•••

In facing the climate challenge we can’t afford to quarantine forestry, or any other activity, from scrutiny, or put vested interests ahead of the truth.

We most certainly can’t allow any stepping-up of native forest clear-felling over coming years in anticipation of a future ban.

But it’s vital that rural communities continue to thrive, deriving nourishment and wealth from the land, and that is everyone’s responsibility: loggers, conservationists and the rest of us. These same communities, as food-producers, may turn out to be our lifeline.

We must heed the warnings about the extreme danger of carbon pollution, put politics and squabbling aside, and change how we manage our forests. Together.