Denying a human factor in climate change is a win for instinct over reason. People in authority who choose the path of unreason, taking refuge in denial and ignoring the expert knowledge available to them, are putting our future in jeopardy. [5 January 2010 | Peter Boyer]

What’s natural, and what isn’t? If we take carbon from natural storages and burn it, for instance, is that something artificial or are we just doing what comes naturally? These questions go to the heart of the debate over man-made climate change.

Late last year I was part of a group putting together a climate change slide show for the Tasmanian public service. “Against nature” was suggested as the title for part of the show about how human activity had changed the face of the planet.

A CSIRO scientist who was advising us questioned the title, saying “there are some who would argue that human behaviour is a natural process, even if it is destructive”. We thought about this and decided to stick with “against nature”.

But what she said has stayed with me. As Copenhagen slipped into a morass of pessimism and despair, I found myself wondering about the juggernaut that is modern humanity and whether, on this global scale, we can ever expect to overcome our powerful short-term desires.

The scientific perception that our carbon emissions are destabilising the climate is a product of reason, of observing changes to our physical world and working out what caused them. Over many decades we’ve done the sums and worked out that we’re adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere too quickly for natural processes to keep up, and that this is threatening our future.

But using stores of carbon in fossil deposits and forests to help drive the vast machinery of our modern life is in a sense as natural as breathing. It’s in the genetic makeup of all life forms to exploit whatever comes along for short-term gain, taking what’s needed and spitting out what isn’t. In nature, longer-term risk is a secondary consideration.

Our human cleverness has taken us a long way. When we found what we could do with the black stuff in the ground, we did it and kept on doing it — all perfectly natural. It’s been a fantastic bonanza and an exhilirating ride. How can we be expected to stop, even for a moment?

For the first time, a species is now confronting the vast consequences of its actions into the distant future. Simply knowing this is a triumph of reason. To meet the much greater challenge of doing something about it will be an achievement unmatched in our history.

We have applied reason before, in a more limited way. We reasoned that revenge, the instinctive (or natural) response to a crime, was no way to manage things on a larger, longer scale, so we invented criminal justice. We wanted to be healthier so we developed health support systems, and we wanted to be better informed and trained so we created schools and universities and training institutes.

All are the product of reason. So is the science that determined that humans are changing the climate, but it’s up against our natural inclination to exploit whatever we can as quickly as we can.

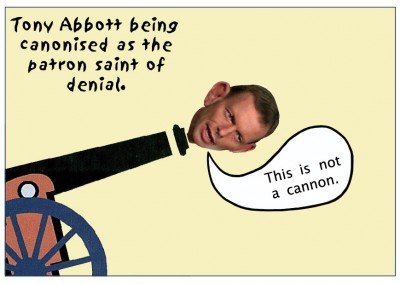

Reason versus instinct: as the science firms up, so it seems does the resolve of those who don’t want to believe it. The climate denial campaign claims to have reason on its side, but for the most part it’s been no more than an instinctive defence of the status quo. Perfectly natural. Perfectly mindless.

We thought that collectively we should behave rationally, so we created government and business systems and charged our leaders with thinking before acting. With access to the best expert knowledge, it’s reasonable to expect them to be alert to the long-term dangers of carbon pollution.

So when people in authority take the road of unreason by denying there’s a human factor in climate change, we’re within our rights to ask why. Are they, maybe, just fearful of losing a way of life they’ve come to depend on, like many other ordinary folk? Or do they have less worthy motives?

Climate policy demands that we set aside short-term enticements for the sake of longer-term security, acting promptly and decisively, at some expense, and curtailing or abandoning some cherished habits. But as this election year gets under way, we’re seeing unscrupulous politicians going for the enticements regardless and attacking the cost of a long-term plan.

As for business people, money talks. It’s no surprise to see airline and electricity company executives take their cue from the power shift in conservative politics and claim, as they did last week (egged on by the likes of Senator Nick Minchin), that a carbon price will lead to a downturn in Australian tourism and travel, or higher power bills. The boardroom tends to favour this year’s profit over next year’s vision, whatever the longer-term dangers.

Getting decisive climate action on to political and business agendas was a hard slog. Labor took up the cudgels in 2007, belatedly and without a lot of enthusiasm, because the Howard government was so clearly failing public expectations.

Climate deniers in positions of authority are gambling that these public expectations can be manipulated, giving oxygen to the business-as-usual brigade everywhere to push for an easing of emissions policies and targets.

It’s never easy to put a tough message out to people who are understandably tired of argument and adversity. The easy option is to say it’s all make-believe and put it to one side. The politics and business of greed and delusion may win short-term benefit, but at an incalculable long-term cost.

Natural or not, I’d like to think that we were capable of better things.