Our climate future is being unfolded before our eyes. We can ignore the implications, or make early planning decisions to deal with them. [12 October 2010 | Peter Boyer]

Our climate future is being unfolded before our eyes. We can ignore the implications, or make early planning decisions to deal with them. [12 October 2010 | Peter Boyer]

What’s ahead? Since the year dot, humans have been asking that question. Our history seems to record more stuff-ups than successfully implemented plans, but there’s also plenty of evidence that we can gain from having a vision and sticking to it.

This week a couple of major studies of future climate provide an opportunity to Tasmanians to look far into their future and begin planning for long-term changes that now seem inevitable.

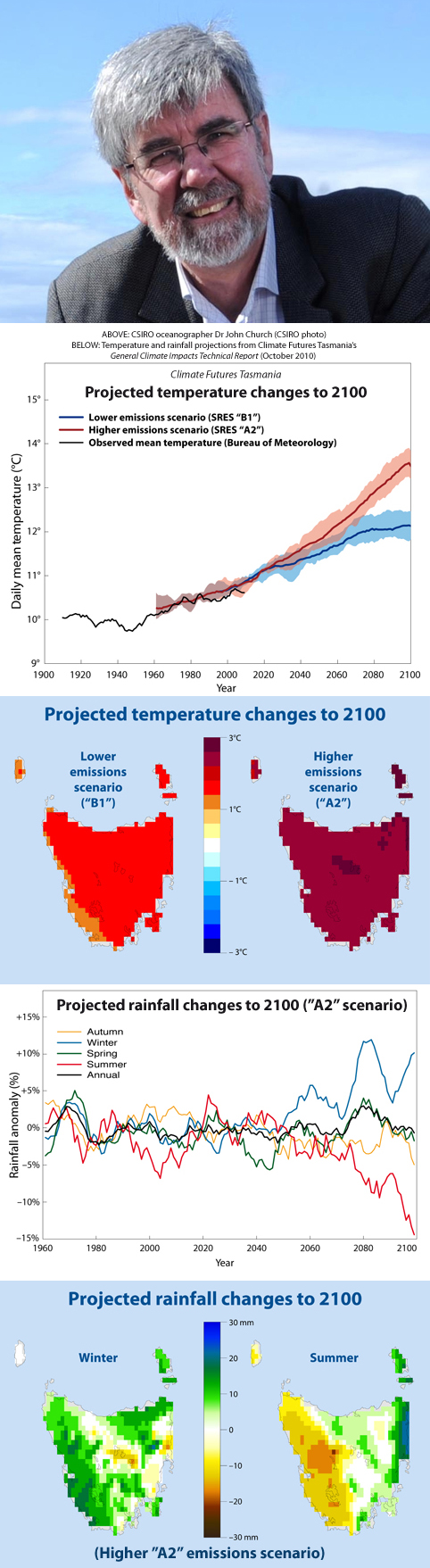

Coastal planners will find much to think about in a comprehensive new book on sea level research, Understanding Sea-level Rise and Variability. Tasmanian oceanographer Dr John Church, one of the four leaders among multiple international contributors to the book, will introduce it to a global climate conference starting in Hobart tomorrow.

The book summarises past changes to sea levels and what we know today about causes and effects of sea-level rise, and assesses the impact on coasts of a rising incidence of extreme weather events.

It calls for more robust, integrated data on ocean and ice sheet monitoring and modelling, so that coastal peoples throughout the world are more aware of how rising sea levels and weather events will affect their own regions.

This week’s other big event is the release today of a landmark report on Tasmania’s future climate by the Minister for Climate Change, Nick McKim. General Climate Impacts is the culmination of three years’ work by climate modellers under the auspices of Climate Futures Tasmania, a government-sponsored research program based at the University of Tasmania.

Climate everywhere is a complex business, but on this mountainous Southern Ocean island it’s especially so. As a technical guide to our present and future climate, General Climate Impacts is about as good as you’ll get.

It reminds us that Tasmanian temperatures have risen since the 1950s, but at a slower rate than in mainland Australia. Since 1975 rainfall has generally decreased, especially in autumn, with dominant subtropical ridges of high pressure north of Tasmania intensifying and taking a more southerly course.

In developing long-term projections, Climate Futures researchers simulated Tasmania’s future climate under two internationally-recognised scenarios of rising greenhouse gas emissions, using six global climate models incorporating the main components of Earth’s climate system.

The group drew on more expertise and a much greater volume of data than any previous Tasmanian study. Its world-leading modelling software applied the data on a 10 km grid across the state’s land areas, taking account of local topography, to produce climate projections of unprecedented detail. The projections correlated strongly with observed measurements over the past 40 years.

There’s far too much detail in General Climate Impacts to cover it all here. Broadly, the report indicates that by 2100 we will have warmer conditions (especially warmer nights) and significant changes in rainfall patterns from region to region.

• Tasmania’s mean temperature will rise by close to 3C under the high emissions scenario and about 1.6C under the low emissions scenario — in both cases less than the global average due to the moderating influence of the Southern Ocean.

• Increasing temperatures will lead to decreased average cloud cover, increases in both evaporation and relative humidity and stronger winds in spring.

• Sea surface temperature off eastern Tasmania will continue to rise, caused by a southward extension of the East Australia Current, also helping to bring more rain to the northern east coast.

• Tasmania’s total annual rainfall is not projected to change much over the century, but there are significant changes in the regional pattern of rainfall across the state, with less rain over central and north-western Tasmania and more in coastal regions.

• There are likely to be marked changes in seasonal rainfall, with the west coast much wetter in winter and much drier in summer after 2050, and the central plateau drier in all seasons. A narrow strip along the northern east coast is projected to get much more summer and autumn rain.

Projected rainfall trends fit with expected changes to pressure patterns, sea surface temperatures and other large-scale climate drivers. Mean atmospheric pressure is projected to be higher around Tasmania, associated with the southward shift of subtropical high-pressure ridges driving the changes to west coast rainfall.

The report doesn’t spell out in detail what we have to do to prepare, but what it has to say about our island climate should galvanise anyone with an interest in our future well-being. It will be of more than passing interest to farmers and others living off the land, and essential reading for all town and regional planners.

Climate is a leading indicator of our well-being, so the report’s information isn’t just for technical and agricultural people. It’s also for policymakers — the politicians whose job it is to determine the big picture and frame our laws, and the public servants who help them.

It would be no bad thing for the rest of us, who elect the politicians, to get engaged too. After its public launch, the report may be downloaded from the Tasmanian Climate Change Office.