Anxiety about future energy security is a big factor in the inability of nations to reach agreement on carbon emissions. Peak oil will soon become a big headache for Tasmania. [7 December 2010 | Peter Boyer]

The balmy seaside air of the Mexican resort city of Cancún seems no more conducive to global agreement on climate action than last year’s wintry Copenhagen, and we don’t need to look far for the reason. It’s summed up in one word: energy.

The debate is getting louder as the stakes rise. At every level, from the personal to the international, we’re having to endure more fractious meetings, more noisy posturing, ever-angrier bloggers and commentators.

This is not good news for political leaders, of whatever shade. For years they’ve sought to cast a moderating light on the climate challenge, presenting it as an issue that goodwill and determination will resolve over time. But they have reckoned without the rising threat of energy scarcity.

Our thirst for energy has driven the times we live in, a colossal binge fuelled by black stuff from underground. Our coal and oil deposits took millions of years to form. We’ve managed to extract nearly half of them in a couple of centuries, and most of that within the last few decades.

The mining of coal, oil and natural gas, this one-off event in Earth’s history, has provided us with astonishingly concentrated energy. Fifty litres of petrol yields the same energy as a day’s labour for 1000 men. Without a thought for such things we pour more than that into our tanks each time we fill up.

To put it another way: an average fit man uses half a kilowatt-hour of energy to complete one day of physical work, but the same amount of energy can be provided by around two tablespoons of petrol. At today’s prices that would cost around seven cents. Is that what a day’s labour is worth?

Fossil energy has fuelled unprecedented economic growth that’s given us today’s technology-driven lifestyles. Virtually everything in our modern lives, from electricity, transport of goods and people and all our personal and household gizmos to clothing and medicines, is dependent on it.

More, it’s provided the fertilisers that have enabled 6.8 billion people to survive and thrive on a planet that otherwise could sustain only a fraction of that. Food is life, and without the black stuff we’d be in big trouble. For every calorie of food on our table, on average five calories of fossil fuel have been used to get it there. In a sense, we eat oil.

The billions of tonnes of coal, oil and gas that we’ve burned have produced enough carbon dioxide to change the state of the planet, and the effect of this burning will be felt for thousands of years even if we stop now. The impact will be greater the longer we go on, so perhaps we should be relieved that reserves of oil, coal and gas are finite.

All those in the know — the scientists, the miners, the bureaucrats and politicians — now concede that the good times are coming to an end. Numerous national and international reports over the past couple of years have confirmed this. The only question is when.

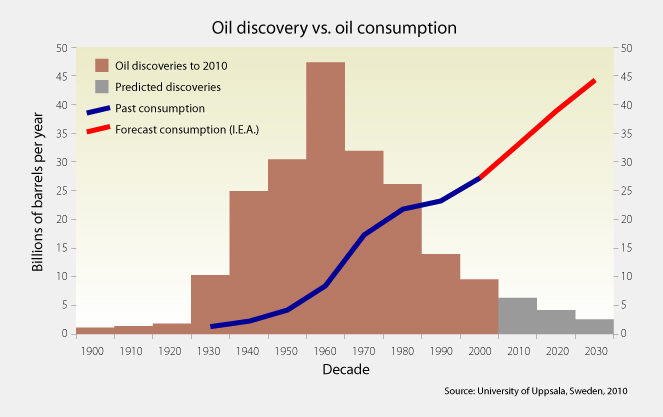

Most analyses give us no more than 10 years before we pass “peak oil” — the point at which extraction costs averaged across the globe begin an inexorable rise because the wells are emptying, remaining oil has to be forced out, and new wells are difficult to access. Some say we’ve already passed it.

The energy-sensitive among us argue that there will always be new sources to plug the oil gap. They point to the Canadian tar sands, ignoring the enormous energy involved in heating the tar to extract it, or to the world’s enormous coal reserves, in Australia no less than elsewhere.

But here, too, it seems we’re heading for a peak. A study by a non-aligned energy research team at Sweden’s Uppsala University concludes that at today’s increasing levels of exploitation we have a mere 20 years before coal supplies begin to drop, caused by decreasing quality and increasing difficulty (and therefore cost) of extraction.

For Tasmania, the main problem isn’t coal but oil. Some of our vulnerabilities we share with the rest of Australia, such as all those goods and services that keep our developed lives afloat, but the big issue for us is our transport fleet.

Apart from a tiny local biofuel contribution, imported oil or gas is the sole fuel supply for all our trucks, trains, buses, vans and, yes, our private cars. Without the regular tanker visit, we’re pretty well stuck where we are.

About 70 Tasmanians got together in Hobart recently to put their minds to what peak oil might means for this island, down here at world’s end. A full day of discussion yielded a welter of information and ideas for confronting a fuel-challenged future.

Alternative technologies were discussed, including electric cars and biofuels, but participants came to see that technology is at best only a small part of the answer. For instance, we can’t grow enough biomass to meet today’s level of fuel usage, even with marine biomass factored in.

The forum found that long-term changes in patterns of personal and social behaviour will be needed, involving some unavoidable difficulty, dislocation and lifestyle shifts, but the impact of these can be mitigated by effective government and community planning.

For that we need foresight — leaders prepared to think ahead and people prepared to support them. What are the odds?

• As part of a $250,000 study called “Prosperity Beyond Peak Oil”, the Tasmanian Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources will be seeking public submissions early next year.

• The Hobart Peak Oil Forum led to the formation of Peak Oil Tasmania; for more information contact Sustainable Living Tasmania, tel. 62345566.