Town and country are joining forces in a big revival of local food. [1 April 2014 | Peter Boyer]

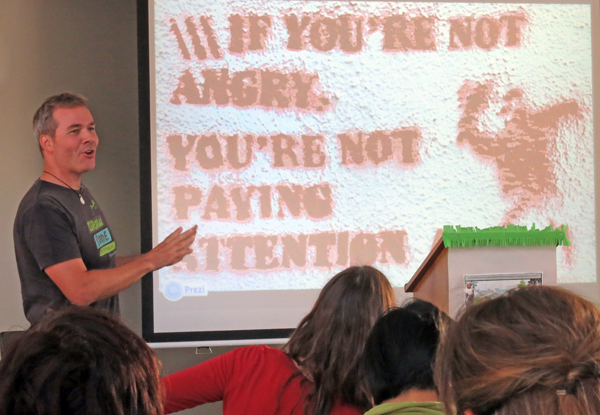

Dr Nick Rose of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance makes a point at the Food 4 Thought national conference.

On World Environment Day in June last year, when Australians were diverted by Julia Gillard’s battle to save her prime ministership, her agriculture minister launched a $1.5 million program called Community Food Grants.

Senator Joe Ludwig made much of the tiny program, an offshoot of the National Food Program launched a fortnight earlier to help build national food capability.

The grants weren’t easy to come by, requiring applicants to find equivalent amounts from others in cash or equipment, yet the offer attracted 364 applications to set up cooperative food gardens and city farms, farmers’ markets and the like. For many small communities that was no mean feat.

Their effort would have heightened the disappointment they felt in February on being told in a letter from the federal agriculture department that a “tight fiscal environment” had put paid to the scheme.

Then to add insult to injury, national vegetable grower organisation AusVeg said it was pleased the scheme was axed, claiming it posed “a potential risk to the national horticulture industry”. Many community gardens, said AusVeg, were run down and didn’t meet commercial standards.

But a commercial grower attending “Food-4-Thought” the sixth national community food-growing conference in Hobart last week, would have left assured that there was nothing to fear from a resurgent local food sector, and wondering what all the fuss was about.

In fact, says Costa Georgiadis, presenter for the ABC’s Gardening Australia and a keynote speaker at the conference, food gardens don’t compete with commercial growers, which supply big retailers and the export market. They support local communities by helping to market seasonal, local food.

As for the conference delegates, representing an estimated 60,000 community food workers and volunteers around the country, they shrugged off the disappointment of losing the grant money, treated the AusVeg attack as a misunderstanding, and got on with their business.

And what a business it is. Peta Christenson (Cultivating Community), Chris Ennis (Centre for Education and Research in Environmental Strategies), Kirsten Larsen (Eco Innovation Lab, Melbourne University) and Nick Rose (Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance) opened a door on the huge possibilities opening up in the sector in Melbourne and Sydney.

As they told it, farms and community gardens located in Australia’s major cities are teaching people to produce food in new ways, helping them develop marketing skills, and providing food for restaurateurs now developing menus for locally-grown food and meat.

In this UN-declared International Year of Family Farming, farms and gardens in Melbourne are now providing for half a dozen kinds of outlets: the Open Food Network, farmers’ markets, online sales, small retailers, restaurants and “fair food” wholesalers.

They are helping small retailers to sell their wares under a local food banner, emphasising the value of supporting producers and other local businesses to strengthen the local economy, and helping to eliminate food waste by setting up “food to farm” composting services.

And they are bringing all these threads together in the Melbourne-based Open Food Network (OFN), describing itself as “a free, open-source, scalable e-commerce marketplace and logistics platform” for communities and producers to connect, trade and co-ordinate movement of food.

OFN is a network of online farmers’ markets, open for everyone to take part. By allowing products to be traced from farm to table, it puts control over food back into the hands of farmers, consumers and local enterprises. Potentially, this is a revolution in direct farmer-to-eater communication.

Inspired by similar US and UK online ventures, OFN is planning to expand well beyond Melbourne, setting up the Open Food Foundation as licence holder of open source software providing local groups everywhere with a free, easy-to-use online food management tool. What about the role of government?

If the abandonment of Community Food Grants and the 2013 National Food Plan is any guide, government in Australia is not much interested in supporting local food. But other governments, such as Ontario, Canada, have a very different attitude.

Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, took two huge steps to a more sustainable future in 2013. It became the first jurisdiction in North America to ban coal-fired energy production, and it passed a Local Food Act to foster successful, resilient local food systems and economies.

Ontario, which has strongly supported locally-grown and marketed food since the 1970s, has invested more than $116 million over the past 10 years in promoting and celebrating the province’s produce.

Here’s where local food starts to go mainstream: Ontario’s local food laws include a 25 per cent tax credit for farmers who donate their produce to eligible community food programs, such as food banks.

Canada shares a great deal with Australia, including a federal government unwilling to take firm action to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. If a Canadian province can achieve a Local Food Act, why can’t a certain “clean, green” Australian state?

• In the next 15 years $100 billion is to be spent on developing new coal mines in Queensland and NSW. This will involve the savings of ordinary Australians, raising the question, are fossil fuels bankrupting our nation financially as well as ecologically?

This will be the subject of a live video feed tonight (6-7pm) at the Centenary Theatre, University of Tasmania (Grosvenor Street, Sandy Bay), from the University of Melbourne, where Ben Caldecott, founder of Oxford University’s Stranded Assets Program, will be guest speaker.