With global temperatures soaring, the pressure for a successful outcome in Paris will be huge [24 November 2015 | Peter Boyer]

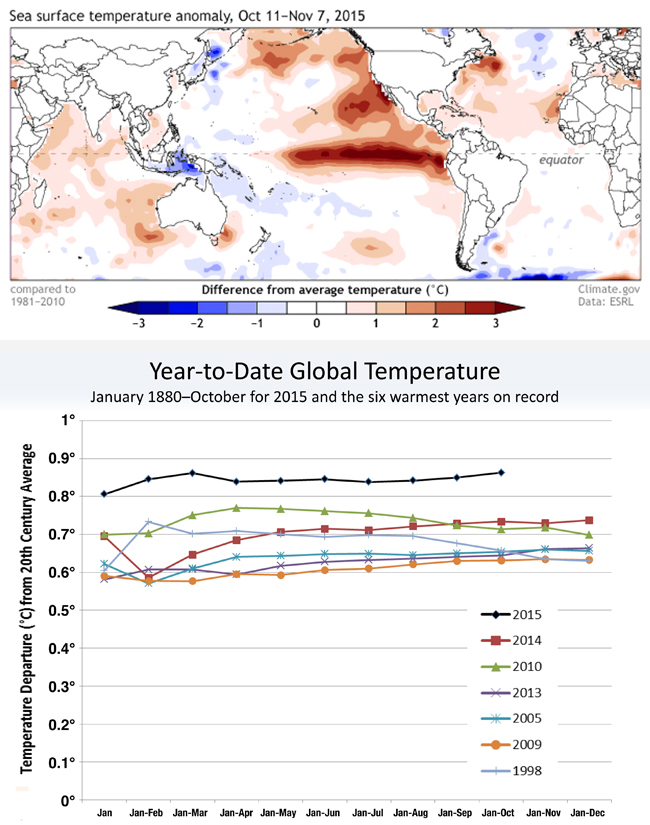

Sea surface temperatures in October (top) and temperature comparisons (bottom). IMAGES courtesy NOAA

It’s happening. Heat energy stored by the global ocean is now being released to the air around us, and the big burst of global warming anticipated for years by climate scientists is upon us.

For 15 years the world’s ocean has been taking up greenhouse energy from the atmosphere and storing it in its depths. Now some of that heat is escaping, courtesy of a big El Nino event in the equatorial Pacific.

Since 1998 there’s been a succession of moderate and short-lived El Ninos, but this year’s looks as if it may rival the 1997-98 event, the most powerful on record.

There was no El Nino in 2014, but even so the mean global surface temperature in that year was the warmest ever recorded. Scientists then said it looked as if it could be the start of something bigger again. They also reminded us that nothing is certain in global climate.

But by mid-2015, warm waters of the eastern tropical Pacific had finally begun to push westward – the mark of a developing El Nino.

Last week Japanese and US government agencies released data for the year to the end of October, with the message that 2015 is more than 95 per cent certain to be the warmest year ever recorded.

October was a killer month. Its global mean, NASA says, was 1.04C above the October average since records began in the 19th century – the biggest-ever departure from monthly averages and the first time NASA has recorded a monthly anomaly exceeding 1C.

There are a couple of startling images in information released last week by America’s National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

One is a current sea surface temperature map. Most colours vary from patches of pale blue, showing cooling waters, to bigger areas of pink-shaded places (warming waters). But the eye is drawn to the eastern and northern Pacific, where large splashes of deep red depict extreme warming.

The other is a graph comparing month by month temperatures through the warmest years on record, with the six warmest years all clustered within a range of 0.2C. But the progression for January to October this year is way out on its own, clear of the next highest by an exceptional margin.

It’s impossible to view these images without a sense of foreboding, especially in Australia at this time of year when the twin scourges of drought and fire are always in the back of our minds.

Australia has just had its warmest October on record, and searing heat across the continent last week suggests November may be not far behind. Heat and drought have brought a high risk of wildfire to all southern states and left us with depressingly low hydro storages.

The current El Nino is expected to start decaying over summer, but underlying warming is expected to continue thanks to a positive, or warming, phase in long-term Pacific surface temperature cycles.

We know that if we don’t radically reduce greenhouse gas emissions the task gets tougher as each year passes. Yet the Global Carbon Project calculates that recent emissions have been higher than ever, around 10 billion tonnes of carbon a year and rising.

It gets worse. A veteran UK carbon scientist calculates that keeping a temperature rise below 2C would leave us with half the fossil fuel that we thought we’d have available to burn up to 2100.

In a paper published last week in Nature Geoscience, Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall climate centre notes that the scenarios on which current targets are based are implausible or impossible, and assume we’ve already passed peak emissions when we haven’t.

What should we be saying to the world leaders soon to gather in the beleaguered city of Paris to chart a way out of these dire straits?

If they want history to remember them well, they will need courage and a long view. Decisions of any value will inevitably bring prolonged economic disruption. Though some people will find the challenge exhilarating, there will also be anger and distress.

This is a task for a lifetime and beyond, a long, hard slog for governments, business and the rest of us. But leaders should be aware that an informed public, knowing the awful consequences of failure, will support decisive action.

For people who won’t be in Paris but feel they have a stake in the outcome (and who doesn’t?), rallies next weekend will fill public spaces in cities around the world, including all Australian capitals and many regional centres. Tasmania’s share of this massive global mobilisation will be a rally on Parliament Lawns, Hobart, from 1 pm on Sunday, and an event at Burnie Park from 2 pm on the same day. Click here for information.