Looking back over 50 years to the exhilarating and sobering experience of seeing our planet from afar

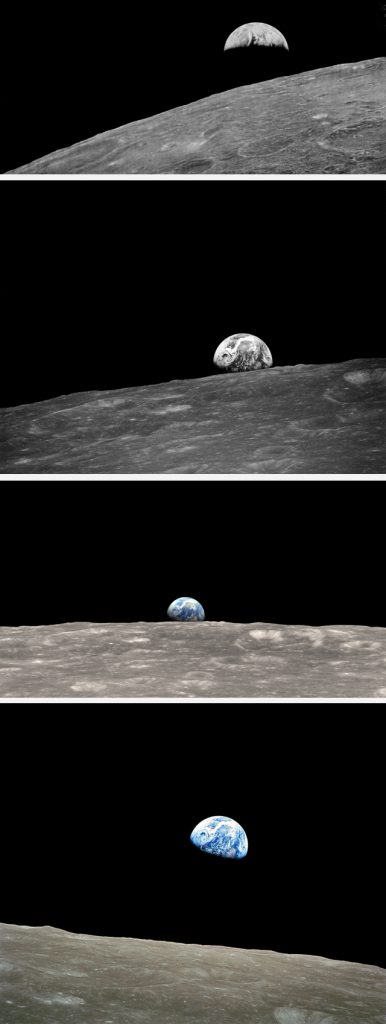

Four Earthrises (from top): Lunar Orbiter, 23 August 1966; Anders’s first photograph, Apollo 8, 24 December 1968; NASA’s colour enhancement of above; Anders’s iconic colour image, 24 December 1968. PHOTOS NASA

Earthrise. The whole idea is other-worldly. Down here on terra firma, rising is done by the sun and the moon and the stars. But Earth?

It takes an effort to get the head around an Earthrise. You have to imagine being on another celestial body, able to see the whole of our planet as it appears over the horizon. No-one thought about it much until NASA started to capture images in space.

In August 1966 NASA’s first unmanned Lunar Orbiter spacecraft transmitted to the world an image of a crescent Earth coming into view above the surface of the moon – our first Earthrise.

A year later another Lunar Orbiter looked back on its way to the moon to capture the first photograph of the whole planet, showing Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean under swirling cloud.

Both those transmitted images were streaky, grainy and colourless. We knew they were real and that was truly wondrous, but something much better was just over the horizon, so to speak.

Fifty years ago, on 21 December 1968, the US launched Apollo 8, the first manned moon flight. It didn’t land (the Apollo 11 mission would do that seven months later) but it did make nine orbits of the moon through that Christmas.

On Christmas Eve Bill Anders, one of Apollo 8’s three astronauts, was recording the moon’s surface using black-and-white film (no digital then) in a medium-format camera. During a rolling manoeuvre he saw something that made him catch his breath and exclaim, “Oh my God.”

Coming up over the barren lunar horizon was the sparkling blue and white orb of Earth. Anders swung the camera and snapped an image of Earth appearing above the horizon, then called for colour film as his home planet seemed to soar into the heavens.

Jim Lovell, best-known now as commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13, shared his crewmate’s excitement as he found colour film. “I think we missed it” said Anders as the spaceship continued to roll. “Hey I’ve got it right here,” called Lovell, looking out another window.

The voices reveal that the two men knew this was something very special. A pause on the voice recording as Anders loads colour film into the camera is followed by a satisfied “Okay”, then from an anxious Lovell, “Now vary the exposure a little bit.”

Anders: “I did. I took two of ’em.” Lovell: “You sure you got it now.” Anders: “Yeah… well it’ll come up again I think.” As it happened Earth didn’t “come up again” on that mission, but it didn’t matter – Anders had “got it”.

In 1999 Time and Life magazines rated the colour image by Anders as one of the 20th century’s great photographs. It has been called “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken”.

The “pale blue dot” that is Earth can be seen in the upper band on this image captured by Voyager in 1990. PHOTO NASA

There’s a postscript to this story. In 1990 the unmanned spacecraft Voyager 1 was six billion kilometres from Earth when, at the request of the eminent physicist Carl Sagan, NASA directed its camera back toward its home planet.

The resulting pictures, which took three months to transmit back to Earth, included another iconic space image of our planet. No outlines of continents or swirling clouds this time. Earth was a tiny blue speck – in Sagan’s words, “a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam”.

“That’s here,” wrote Sagan. “That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.”

In their different ways, both pictures provide compelling guidance to a post-Apollo, post-Voyager age. In them we see our home as we might see other heavenly bodies in a Hubble space image, isolated and finite; in the words of Anders, an “oasis in the vastness of space”.

Bill Anders wrote of his life-changing Apollo experience, “We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

In our quest to grasp what it is to inhabit Spaceship Earth, Anders and a handful of astronauts – the only people ever to have seen our planet’s orb in all its splendour – have the advantage over us.

But I have a small sense of what he means. I have been privileged to live for two short periods in magnificent, desolate Antarctica. And yes, I am aware that Antarctic travel, like space travel, comes at a large cost in energy and resources. It’s arguable that humans should not go there at all.

Memorable as those Antarctic experiences were, I took away from them something much better: a renewed sense of our great good fortune to live in this wonderful part of our precious mote of dust.

Now we need to find the incentive to stop trashing it. Those 50-year-old Earthrise images are a pretty good place to start.