We’ve come a long way since the life and death of Freddie Mercury.

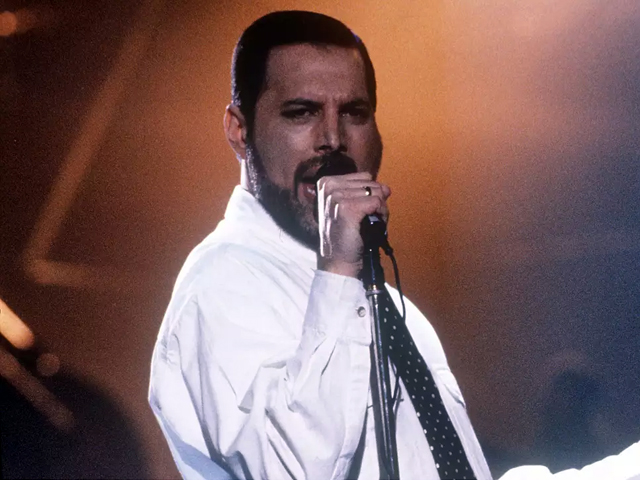

The incomparable Freddy Mercury. PHOTO Rex

The terrific new Freddie Mercury biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody, brings to mind how much things have changed since those rip-roaring years when Queen was at the top of its game.

Replete with the songs and stagecraft that made Queen and especially their lead singer so beloved around the world, the movie pays homage to one of the great musical and performing talents of our time. Rami Malek’s portrayal of Mercury is worthy of a best-actor Oscar.

Mercury’s Parsi upbringing in Zanzibar and India and his family’s migration to the UK are touched on as background in Bohemian Rhapsody, but the movie’s focus is the central part of his life, when his and Queen’s stars were in the ascendency.

The movie is about Mercury as an artist, and no Queen fan would want it any other way. While making it clear he was gay, it merely alludes to his unusually active sex life. But it’s impossible to ignore this in light of all that has happened since.

Mercury had strong family ties and respected the institution of marriage as it existed then. For several years his partner was a young woman, Mary Austin. She remained a lifelong friend.

In the mid-1980s he learned he had HIV. He kept his sexuality and his illness private, never discussing them in public, but events overtook him. Back then the disease was considered untreatable, and in 1991 it killed him. It was bad timing; a decade later he would have survived.

Homosexual acts between consenting men had been decriminalised in England in 1967, but that didn’t end persecution of homosexual people there. Everywhere in the world, embracing sexual and gender diversity has been a long, hard journey which continues to this day.

Here, Australian jurisdictions one by one abolished anti-gay laws, starting in South Australia in 1975 and ending in Tasmania in 1997. They were great victories for civil society, but they didn’t end discrimination. There was and still is much left to be done.

Steadily shifting public attitudes have driven change. Twenty years after the Tasmanian breakthrough, opinion polls showed a big majority of Australians favouring equal treatment of all people regardless of their sexuality or gender.

That should have been enough to see legislation for marriage equality pass easily through the federal parliament. But that happened only after a difficult and for some traumatic campaign last year forced by a small minority of MPs who objected to a free parliamentary vote.

It’s now enshrined in law. Same-sex couples now enjoy the same rights to marriage as the rest of us. This is something we should all celebrate. Yet there remain some who choose not to celebrate. At the heart of this opposition are religious organisations which teach that homosexuality is sinful.

“Scripture teaches that sex is God’s gift to humanity, only to be expressed within the marriage of a man and a women,” says the website of Sydney-based Liberty Christian Ministries. It seeks to “liberate” people of faith from “the problem” of same-sex attraction.

There are various approaches. Some organisations say they oppose “aversion therapy”, which seeks to turn a person’s homosexual desire into something unpleasant. But all of them cast homosexuality as unnatural, outside God’s laws.

That flies in the face of the finding by the American Psychiatric Association that homosexuality and bisexuality are “normal and positive variations of human sexual orientation”, and that aversion or conversion therapies cannot actually change sexual orientation.

Whatever the scriptures may say, science tells us that a person’s sexuality stems from an interplay of genetic, hormonal and environmental influences, and that homosexuality has nothing to do with bad parenting or early childhood experiences.

Numerous scientific studies in many countries, including Australia, have found that homosexuality is not a choice, but should be seen as a natural expression of human sexuality. That position was endorsed by most Australians in last year’s marriage equality survey.

Even so, a minority among us continues to assert that there is a right kind of sex and a wrong kind. Once that belief held sway across many religions; now we know it is simply untrue.

Had Freddie Mercury survived, he would have seen the stigma of being gay all but disappear. He would have experienced the relief of acceptance by society at large. He could have dropped all the subterfuge and deception, the little lies he felt forced to use to disguise what he really was.

He paid the ultimate price for living life on the edge. We may have benefited from that edginess in his songs and stagecraft, but we should never wish it on anyone. Everyone benefits when society at large accepts all shades of sexuality and gender as part of humanity’s rich tapestry.