At last, a climate policy from a major party worth a second look.

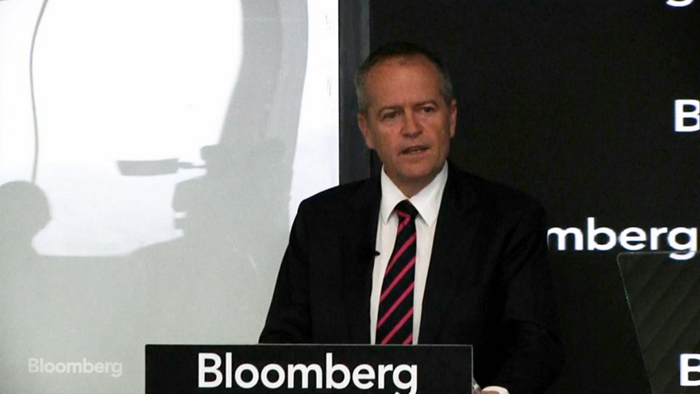

Bill Shorten delivers his energy plan. PHOTO Bloomberg

It’s hard to share Bill Shorten’s excitement about his grand vision for Australia’s energy future when every other such vision has turned to mush in the meat-grinder of party politics.

But coming from the leader of the party hotly favoured to take power after the next election, Shorten’s plan has struck a chord with many in business and academia. Could it be that after all the wilderness years we have something to look forward to?

A Labor victory looks even more certain after Saturday’s rout of the Coalition in Victoria. Plenty of factors were in play there, but climate change was undeniably one of them, especially in Melbourne’s affluent east and southeast. Just as it was in affluent Wentworth.

Business – notably the Business Council of Australia – has reacted positively to Shorten’s promise to work with the Coalition to implement the National Energy Guarantee, crafted by Josh Frydenberg when he was energy minister and supported by Scott Morrison as treasurer.

The NEG in various forms was approved in three Coalition party room votes this year. Each time a disgruntled minority threatened to vote against it, causing then-PM Malcolm Turnbull to set it aside.

Seizing the middle ground is the aim of Labor’s endorsement of the NEG, on which it is likely to base a yet-to-be-defined emissions trading scheme, probably to include transport.

That wasn’t the only shared policy space. There is more than a hint of Tony Abbott’s “direct action” in Shorten’s 10-year energy investment plan to directly underwrite renewable investment through a “contract for difference” auction scheme.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation loans for renewables will be boosted by $10 billion, and Labor will empower the Australian Renewable Energy Agency to help us use energy more efficiently, for which Australia is rated last among developed countries by the International Energy Agency.

A $5 billion transmission and distribution fund will go to upgrading interstate interconnectors and building new ones, including a second connection across Bass Strait, and support for strategic storage initiatives including Tasmania’s ‘‘Battery of the Nation” pumped hydro proposal.

Aiming to make solar power available at any time of day or night, Labor will set a national target of a million new household battery storage systems by 2025, offering low-cost financing through the CEFC and a $2000 rebate for 100,000 battery installations in lower-income households.

Shorten promised $100 million to create a community power network, setting up 10 community power hubs to provide legal and technical advice and start-up funding for local renewables projects.

Australia, already the world’s biggest supplier of lithium, will see a radically expanded battery industry under Labor, which claims a skilled workforce, advanced mining technology and high-quality scientific research all point to Australia becoming a leading battery maker.

Shorten pointed to modelling showing that as many as 60,000 new jobs could be created if it pursues its 2030 target of 50 per cent renewable electricity. He also promised to set up a “just transition authority” to help the coal-power industry and its workers make the shift to renewables.

This all sounds absolutely fabulous. I should be the last to be critical of a plan to set Australia back on the path to a clean energy future, and I applaud Shorten and his party for taking this significant step forward. But there are also significant caveats.

Labor’s 2030 target is 50 per cent renewable energy and 45 per cent lower emissions. The Morrison government has walked away from its Paris 2030 commitment of a 26 to 28 per cent cut in emissions but continues to claim that this will be achieved easily.

The October report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, prepared at the request of the 2015 Paris climate summit, has significantly recast the debate about such commitments. That report makes clear that a huge, urgent global effort is required to avoid dangerous climate change.

It is glaringly obvious that the world’s developed nations must lead by example. In Europe, including the UK, there is growing support for national targets of zero net emissions by 2030, even 2025, just seven years away. In Australia, not even Labor can now say its targets are adequate.

One lesson from the history of climate policy in Australia is that few politicians have got their heads around the pressing scientific imperatives that lie behind it. In Shorten’s speech there’s a glimmer of hope that this is starting to change.

“The latest report from the IPCC is unambiguous: climate change is no longer an emergency, it is a disaster,” he said. He went on to argue that the single most important thing about energy and climate policy right now is to have one.

But having a policy is a far cry from having a good policy, and even further from implementing it. For Labor’s policy to have a lasting impact it must have strong national backing, and that has to include bipartisan support. Winning the election would be just the start.