Sea-level rise this century is likely to be much more than the UN climate report predicts, according to Hobart experts. [16 October 2007 | Peter Boyer]

Earlier this year, a report representing the thinking of the world community of climate scientists — the distillation by several hundred scientists of thousands of scientific papers — advised that by 2100 our seas will probably have risen between 18 and 59 centimetres.

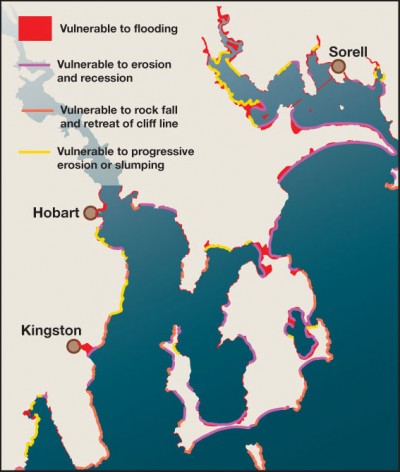

A 2005 study of Tasmania's vulnerability to sea level rise found that even modest projections would have an impact virtually everywhere around Tasmania's coast (SOURCE: Chris Sharples (2006): Indicative Mapping of Tasmanian Coastal Vulnerability to Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise – Report to Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries & Water (2nd edition), May 2006)

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which provides independent advice to help the world’s leaders develop climate change policies, based its finding on the results of 27 separate computer models, crunching an enormously complex array of data.

But there’s a catch. In releasing the full text of its 2007 report, the IPCC advised that its predictions for sea level rises did not take account of “processes related to ice flow”.

If you’re thinking a sea-level rise of, say, 40 centimetres over the next century, or “processes related to ice flow” don’t amount to much, think again.

In the first instance, the rule of thumb widely accepted by coastal scientists is that to get an idea of the likely lateral impact of sea-level rise, you multiply the vertical rise by 100.

So the impact of a 40 centimetre rise would on average extend 40 metres back from today’s coastline.

But it’s not just low-lying land that will be affected by rising seas, as geologist Chris Sharples has found in a detailed report on coastal vulnerability for the Tasmanian Government.

With a likely increase in the frequency of storms this century, the Sharples report identified an array of coastal events, including erosion, recession, slumping and rock-fall, that together make virtually all our coasts vulnerable to even a small sea-level rise.

Which really ought to focus our minds on what’s happening with our great ice sheets in Antarctica (holding 70 percent of the world’s fresh water) and Greenland.

The IPPC report advised that “recent observations” suggested that the ice sheets were increasingly affected by warming, and that this could mean sea-level rises above its 18 to 59 centimetre projections.

It’s sobering to note that actual sea level rises, currently around three millimetres a year, have consistently been at or above the upper end of past IPCC projections.

Around the world, oceanographers, glaciologists and climate modellers are trying to get a handle on how much ice is likely to disappear from Greenland and Antarctica by 2100, and what the likely impact will be on our oceans, including on sea levels.

The senior NASA climatologist James Hansen estimates that this impact could raise our oceans by five metres over the next century. Most sea-level research, however, including that by Tasmanian scientists John Church, Neil White and John Hunter, projects a 100-year rise of around one metre.

Whatever the true figure, the trend is clear: rising seas, stormier seas, and eroding coasts.