Rail is known to be an effective means of mass transportation in a fuel-starved world. Does Tasmania have what it takes to revive its lost passenger rail service? [20 January 2009 | Peter Boyer]

“We welcome you aboard the Tasman Limited. This guide is designed to help you appreciate more fully the most varied and beautiful scenery along the route of the Tasman. The first vista you are seeing is of the Derwent Estuary.”

Words from half a century ago, when a rail trip from Hobart to Burnie was a day-long event. To some experienced travellers it may have been a bit of a bore, but to me in my youth, a ride on the Tasman Limited was an adventure that has stayed with me a lifetime.

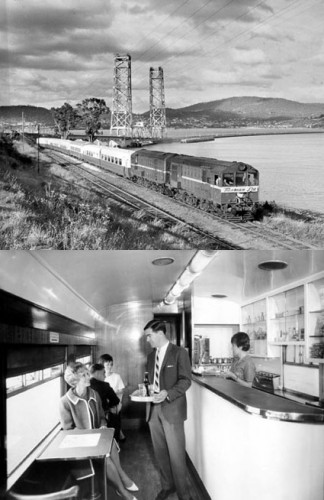

TOP The Tasman Limited approaches the Hobart terminus, about 1959. BELOW Taking refreshments aboard the Tasman Limited in the 1970s (Archives Office of Tasmania)

It was a delight to discover on the Margate online access centre website a description of the Hobart-Wynyard rail trip and its many attractions in a 1950s publication, a 4000-word Tasman Limited tour guide – long and leisurely, just like the journey.

Travelling by road today we make a similar journey, though not by the same winding route, in a few hours, with the added flexibility of using our own cars. Unless you’re into slow travel, this is a clear improvement on the old days. Or is it?

A study of carbon dioxide emissions per passenger travelling between London and Glasgow by Britain’s Institute of Mechanical Engineers last year found that for each air traveller an average of 133.7 kg was emitted for the journey. The figure for road was 80.2 kg, and for rail 46.8 kg.

The disparity is even larger when the different London to Glasgow air, road and rail distances are taken into account. Per kilometre, emissions for each rail traveller are about 70 grams, over 40 per cent less than by road (120 grams). Air travel emissions are off the scale at 400 grams per person.

Road and rail as carriers of freight were compared in a detailed 2002 Australian study which found that, for equivalent tonnages transported, emissions from rail locomotives were at worst 70 per cent of those from road transporters, and at best as low as 31 per cent of the road alternative.

Evidence from everywhere gives rail top billing for energy-efficiency. But in Tasmania it seems not to be an option, and Hobart may soon lose its last rail connection. How has this come about?

First it must be said that our being an island with a relatively small population and commercial base makes it harder for rail than in, say, North America, Europe, Japan or Australian trunk routes.

Tasmanian transport economist Bob Cotgrove has put his finger on what no doubt contributed to the decline of Tasmanian rail – the hugely important role of cars and roads in our lives, and the likelihood that we’ll yield this territory very, very reluctantly.

But climate and related factors, such as the energy-inefficiency and consequent rising cost of manufacturing and using single-person transport vehicles, are forcing us to bring rail back into the transport equation.

Today we’re happy to see governments spending taxpayers’ money to improve roads, which are highly visible in our lives. Since we no longer travel on railway lines they’re out of sight and out of mind, so we pay little heed to their dilapidated state, still on the twisting, turning routes of old.

Early in its life the Howard government committed itself to an expensive new railway from Alice Springs to Darwin. Compared with that 2000-kilometre project, the cost of a new rail link between Hobart, Launceston and the North-West Coast would be tiny.

Strong government and commercial support elsewhere in the world have made rail a highly-efficient and climate-friendly form of land transport. Could it work for us?