Why is it so difficult for people and governments to understand why we must protect our natural environment? [25 April 2009 | Richard Butler]

It was mid-1985 when I got on a plane and flew to Los Angeles and then by bus to Alberqueque and finally to a small and dingy hotel on the outskirts of Santa Fe, New Mexico. I remember the food – yoghurt with a label on it declaring ‘contains real fruit’ and there was a dollop of some kind of jelly jam settled on the bottom, and blue corn chips and guacamole. The next day I got on a bus and then a cab and then walked up some gravel roads to the studio and home of the pioneering colour photographer Dr Eliot Porter – one of America’s most loved and enduring nature photographers.

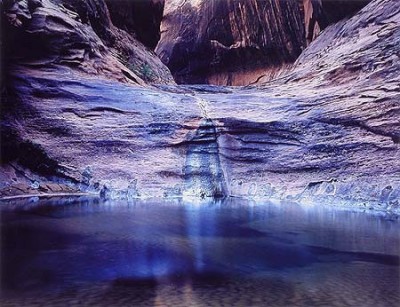

Pool in Mystery Canyon, Lake Powell, Utah, 1964. Photograph by Eliot Porter

Dr Porter was very old, in a wheel chair, but made a huge effort to see me and allow his three live-in curators to pull down any box, from any year of about 60 years of work. I could go through his many books and see the original prints. I went for a morning and stayed four days. My memory of this quiet, sensitive and gentle man remains clear. Snow-white hair, gentle hands and a courtesy and dignity all too often rare in these times. He treated me as a guest and a friend, and I sat and learned a great deal.

There is a point to this nostalgia.

In America there was a place called Glen Canyon, and Eliot had photographed it. David Brower, of the Sierra Club, had written down the facts for all history to know and remember – of a beautiful canyon which was flooded against the will and desire of the public. Like our lost Lake Pedder, like the Franklin River, like Mount Arthur, like Tasmania once was before the harvest, the poison and the human ignorance and ugliness – Glen Canyon was a most beautiful place. The story and photographs were published into a superb book which won many plaudits and in 1964 was voted as one of the ten most beautiful books in the world. The book is still available.

No-one in Tasmania should need reminding of rare places being systematically and summarily defiled and destroyed, but I think this extract from the book’s foreword about ‘The Place No One Knew’, as Brower called it, still resonates here, as it does everywhere:

The Place No One Knew has a moral – which is why the Sierra Club publishes it – and the moral is simple: Progress need not deny to the people their inalienable right to be informed and to chose. In Glen Canyon the people never knew what the choices were. Next time, in other stretches of the Colorado, on other rivers that are still free, and wherever there is wildness that can be a part of our civilization instead of victim to it, the people need to know before a bureau’s elite decide to wipe out what no man can replace. The Sierra Club has no better purpose than to try to let people know in time. In Glen Canyon we failed. There could hardly be a costlier peacetime mistake.

With support from people who care, we hope in the years to come to help deter similar ravages of blind progress.

—DAVID BROWER, Berkeley, California, March 13, 1963

Somewhere around this time (perhaps a year or two later), Pete Seeger was singing ‘where have all the flowers gone’, with the chorus, ‘When will they ever learn? When will they ever learn?’

I am often frustrated at the repeated use of cliche and metaphor when describing the god-awful mess Tasmania is in now, and has been for many decades, but there are those days when one just doesn’t have the vocabulary to describe the mess. David Brower and Eliot Porter, each in their own way, provided an eloquent and timeless expression of our collective anguish at this and all other acts of administrative and corporate vandalism.

* Richard Butler is a Tasmanian living in Melbourne. He is a photographer and lecturer in digital editing. His last major project has been to photograph over 300 people from the Tamar Valley as a record of their concern about the proposed Gunns pulp mill.