It’s hard to know whether Tony Abbott’s accession to opposition leadership is a plus or a minus for climate policy, though early signs aren’t promising. One thing’s for certain: we would be foolish to expect our politicians to solve this for us. [8 December 2009 | Peter Boyer]

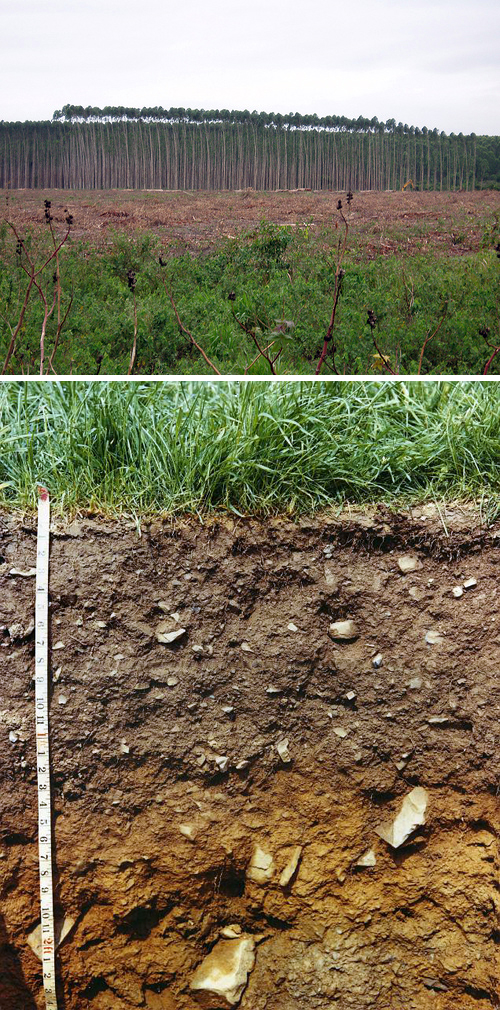

“Green carbon” sequestration in trees and soil may be a key part of Tony Abbott’s new climate policy. PHOTOS: FSC-Watch (top), Soil-net (bottom)

There were quite a few winning camps in the wake of last week’s defeat of the emissions trading legislation, but only one of them was celebrating.

The Greens and independent Senator Nick Xenophon kept a low profile, as did Senator Steve Fielding after getting a pasting on his climate royal commission proposal. But the business-as-usual team that now holds the reins in the conservative coalition partied long and hard.

At the centre of the action were Tony Abbott and the excitable Senator Barnaby Joyce, showing a confidence in their joint future which suggested that maybe they know something about climate change that for all these years has eluded the rest of us, including a bemused Rudd government.

These leaders and their acolytes are set on putting conservative politics back on its true path. Their unexpected victory has left them a bit hazy on the detail, but they’re convinced that with the gods on their side, by golly they’ll put this climate bogy to bed and get on with real men’s politics.

We have reason to be happy at some outcomes last week. We also have reason to be very worried.

It’s good that Labor’s seriously flawed emissions trading scheme, drowning in compromise, has been cast aside. With the free permits it endowed on big business, its unlimited, unenforceable overseas offsetting and its failure to reward individual effort, it could never have done what was claimed of it. But it’s a worry that the coalition rejected emissions trading for all the wrong reasons.

The summer break will provide clean air, so to speak, in which parties, guided by whatever comes out of Copenhagen, might develop a scheme that will ensure every Australian, big business and everyone else, knows the true cost of carbon pollution. But our cracked, fractious political scene (national and international) and the long, painful history of Labor’s emissions legislation give no cause for optimism on this.

Tony Abbott’s prospects are a case in point. Being sceptical about currently-accepted climate science, he hasn’t ever given much thought to climate policy. His rejection of emissions trading was pure opportunism, focusing entirely on the alleged threat to the hip pocket and showing no interest in the basics of Labor’s scheme — in whether or not it was capable of setting a true carbon price.

Setting aside the possibility that he’ll reject climate action altogether, Mr Abbott now has a few short months to devise a whole new plan from scratch, fully costed and modelled, with every detail able to stand up to scrutiny. His plan must be acceptable not just to his immediate followers but also to the broader coalition parties, and ultimately the voting public.

Having so frenetically opposed emissions trading, he’s had to reject that option. Late last month he floated the idea of a carbon tax, but then couldn’t resist attacking emissions trading as “a giant new tax on everything”. So a tax is out. He must now travel a different, untried policy path.

Mr Abbott will certainly focus heavily on big technology “fixes” — nuclear energy is the obvious one — and may re-cast some Rudd government programs supporting renewable energy and electric or hybrid motor vehicles. As a climate sceptic he’s unlikely to be big on behaviour change, though he’s likely to support incentives for walking, cycling and improving energy efficiency in buildings, as well as “green carbon” schemes for carbon sequestration in soil and trees.

But neither technology nor energy efficiency nor carbon sequestration programs will suffice. Every Australian must become aware that there’s a personal cost to carbon pollution. Mr Abbott’s policy must encompass this in a way that no-one’s yet thought of. He’s capable of some original ideas, but this is a tall order indeed.

As for Kevin Rudd, he must travel empty-handed to Copenhagen, his negotiating position seriously weakened by the absence of legislated measures. This is not something any Australian should rejoice about. It should matter to us that our government has a strong hand in this crucial meeting.

In developing its emissions trading scheme the government chose to go down the route favoured by Malcolm Turnbull’s Liberals: making sure big carbon-intensive industries, such as coal power generators and metals processors, are well insulated against potential shocks. It proposes to continue this tack by reintroducing the bill (with the Turnbull-Macfarlane amendments) next February.

But having just gone through the trauma of changing its leader, the opposition under Mr Abbott is unlikely to fracture sufficiently to enable the scheme’s passage through the Senate. And Mr Rudd already has a trigger for a double-dissolution election, so why did he bother?

What this does show is the government’s strong attachment to emissions trading as the centrepiece of its anti-global warming armory, and its rejection of negotiations with anyone but the coalition. Given the opportunity to go away and think about a fresh approach, like a carbon tax, it didn’t even blink before turning back to its old stand-by.

Where does this leave the rest of us? We know Tony Abbott will reject economic or fiscal measures and turn to technology. We know that some good ideas of the Greens and Nick Xenophon to make emissions trading work better will get no airplay while the government remains focused on keeping big business on side, and we know that messy, inadequate compromise will untimately prevail.

What we can do is stand up to be counted. We can start by being better neighbours, building the strength of our communities by initiating small but influential local actions, helping make our workplaces more climate-friendly and generally raising awareness that addressing our climate problems is a matter for us all, much too big to be left to mere politicians.

We can also tell our leaders, at every opportunity, that they ignore climate change at their political peril: that it’s not an option to wish it away or invoke narrow self-interest or attack its science without foundation, and that any legislated solution must make clear the cost of carbon pollution.

Then, when we’ve exhausted all these options and need a rest, we can lie down, close our eyes, cross our fingers and hope.