“Climategate”, though found to be without justification, has shown us how easy it is to persuade people that the scientists are kidding them. We need to go back to basics. [6 April 2010 | Peter Boyer]

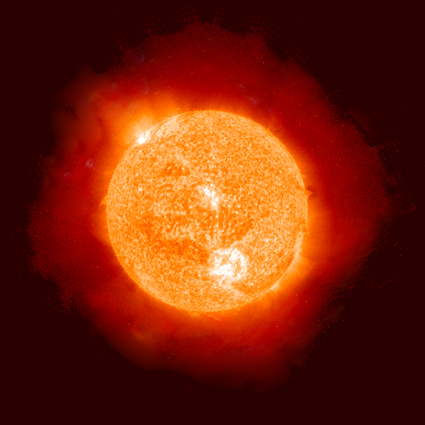

We know we get most of our energy from the sun, but we have much to learn about what happens to it on Earth. PHOTO NASA

It’s official. The furore over emails by UK climate scientists, leaked from the University of East Anglia last year, was baseless. A multi-party House of Commons investigation found there was no scientific fraud, no fiddling with the evidence, no intent to mislead the public. [Click here for the House of Commons media release; here to download the report.]

You’ll probably continue to hear lots more about “Climategate”, which was heaven-sent for some people opposed to prevailing climate science positions. Those people won’t want such findings to spoil a good story.

But while the principal players have been exonerated, the science fraternity as a whole didn’t come out of this affair scot-free. The inquiry took issue with the common scientific practice of not publishing data and computer codes on which conclusions are based.

“Climate science is a matter of global importance and of public interest, and therefore the quality and transparency of the science should be irreproachable,” the parliamentary committee said. It recommended that climate scientists release via the internet enough data and methodology to allow others to verify findings.

In the context of the vast global climate debate, this is an important principle. To get informed decisions on climate we need the science out in the public domain. Releasing data and methodologies for all to see should make it that much harder for baseless accusations to get any traction.

“Climategate” did serve some useful purposes. It showed how scientists ignore public opinion at their peril, and how ignorant the public can be about how science and scientists work. All this plays into the hands of political or commercial interests bent on making mischief with science.

It also demonstrated with startling clarity that the number one challenge facing humanity is not about science or technology, but about us: specifically, how we perceive and respond to what’s going on around us.

In 1862, with a deadly civil war threatening to tear apart the youthful United States, Abraham Lincoln urged his people to “think anew, and act anew” to save their country. In desperate times, he said, people must cast aside old ways of thinking. This great leader understood how an informed imagination can lift a people to achieve things that ordinary mortals thought impossible.

Informed imagination is what we need today to deal with the twin giant challenges of climate change and peak oil. We are talking about education in its broadest, purest sense: the spark that casts familiar things in a new light so that we understand them in a wholly different way.

We’re floundering. These challenges, so big and so new, seem beyond the grasp of many of us in positions of authority: political leaders, bureaucrats, company managers, teachers, doctors, lawyers, and yes, journalists. Along with the rest of us, our leaders seem incapable of making the kinds of mental shifts that Lincoln understood so well.

While the impact of a growing world population on our natural systems makes clear our desperate need to restrain economic growth, our leaders remain fixated on growth. They know that the critical need is to cut carbon emissions now, not in a decade’s time, yet they continue to talk about energy demands as if these are non-negotiable, as if they can’t possibly be curbed.

Why do they do this? Because they believe they’re doing what we want. Like our leaders, we are ignoring the obvious warning signs because they call for new ways of thinking that we’re not prepared to countenance.

I see no short-term answer to this, which is a pity, because acting decisively in the near future will make our longer-term task much less traumatic. But looking further ahead, there is a lot we can do to break our dependence on increasingly vulnerable systems.

This calls for a massive public education effort, touching all ages and all social and economic strata. For this we need to engage communities and workplaces, government and private, as well as all educational institutions — schools, colleges, universities, training institutions, adult education and the rest — with a special focus on young children starting out.

This will not be the education that some of us might recall, constrained to traditional, defined frameworks. It’s rather an exercise in building resilience, enabling us to face the future, if not with complete confidence, then at least with a greater awareness of the pitfalls ahead.

A lot of the information gained will be old knowledge, whereby we get ourselves in touch with things that primitive humans knew instinctively but which, in our 21st century cocoons, we’ve forgotten. We need to re-engage with our good Earth.

Every one of us needs to understand more about how energy works, on both a global and a personal scale. We need to know about the close link between mineral oil and the food we eat, why buying a new hybrid motor car is not always a good idea, how we should determine the viability of a possible new energy source, and so on. This is not an esoteric exercise, but eminently practical.

We all need to be better-informed about how science and scientists work — how observable, measurable evidence is subjected to reasoning, how data is collected and hypotheses tested. We need to improve our critical faculties, to learn how to separate real information from spin, and genuine scientific sceptical inquiry from vested interests posing as sceptics.

Education has been a significant issue in both the Tasmanian election campaign and in the national debate leading up to a federal election later this year. We now have the beginnings of a national kindergarten to year 10 curriculum.

It’s a start, but only a start. We remain firmly locked into traditional learning categories — English, history, science and so on — which will not by themselves meet the larger need of education for life. This debate has a long way to go. Let’s get it under way.