Of all the questions thrown up by Election 2010, there’s none bigger than where Australia is heading on climate change and our growing carbon emissions — and the threat posed by peak oil. [24 August 2010 | Peter Boyer]

Sometimes it takes an outsider to see us as we really are. People like visiting American media specialist Jay Rosen.

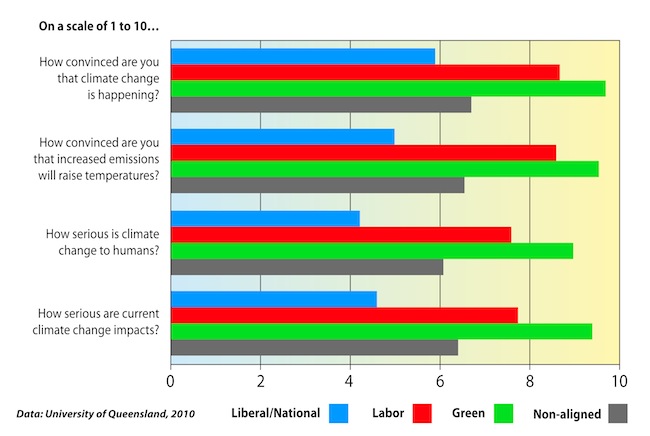

Reaction of politicians to key questions from the University of Queensland survey, “Political Leaders and Climate Change”

In the depths of a shambolic Australian election campaign, Rosen characterised Australian media coverage of the election as “horse-race journalism”, in which stories focus on who’s going to win rather than what the country needs to settle in the election.

This is a cop-out, said Rosen on ABC TV’s Lateline — a sort of journalistic ritual requiring little or no background knowledge and treating the campaign as a sporting event in which trivial aspects take centre stage and things that really matter, such as policy, are cast aside.

Considering Election 2010’s implications for climate and energy policy, Rosen’s analysis strikes a chord, revealing leaders and parties as part of an election machine, also taking in on-line, broadcast and print media, that seems hell-bent on turning this very serious event into a mere entertainment.

So any election analysis needs to take in not just Julia Gillard, Tony Abbott, Bob Brown and all those other aspirants for political office, but also the media that convey their doings and sayings. Ultimately, we also must take a good hard look at everyone else, the consumers of media offerings.

Taking Rosen’s observation about triviality trumping substance and applying it to the way politicians have dealt with (or not dealt with) climate, peak oil and other sustainability matters, we can begin to see why these big issues are making no headway in the public debate.

Take climate knowledge. Over the past few months researchers at the University of Queensland surveyed 310 politicians in federal, state and local jurisdictions around Australia. The result was a minor news story on a single day of the campaign. It should have been a major election issue.

For years now, science has told us that if we don’t manage to contain global warming to less than 2C above pre-industrial levels, we’re in serious trouble, and that going even just one degree above this limit would have catastrophic consequences. It’s also found that absorbed carbon dioxide is threatening ecosystems in our oceans, making it harder for many species to survive.

Despite this, more than two in every five politicians questioned said they thought four degrees of warming would be safe, and 7 per cent of them even believed the same of a six-degree rise. Nearly half didn’t believe scientific evidence that an increasing level of carbon emissions threatens ocean ecosystems.

The party breakdown on the cause of warming turned up a stark divergence. A big majority of Green and Labor politicians (98 and 89 per cent respectively) agreed with the contention from science that human activity is causing warming, but nearly half the independent members and over 60 per cent of Liberal and National politicians thought the warming was natural.

This all helps to explain why climate action, a major issue in the lead-up to the election, got so little airplay during and after the campaign. It would have distracted politicians and their media groupies from attending to what they see as their real business: political tactics, manoeuvrings and gossip.

Gillard and her team have much to answer for in this, as does Kevin Rudd before her. Gillard endorsed Rudd’s capitulation on an emissions trading scheme, refusing to reconsider Rudd’s two-year postponement or to countenance the alternative of an interim carbon tax. In delaying a price on carbon, Labor effectively relegated climate action to a second-tier issue.

But the prize for sheer effrontery must go to Abbott, who in light of Saturday’s vote now presents himself as the rightful prime minister.

Last December Abbott branded emissions trading “a great big new tax”, a meaningless cheap shot that promptly became a mantra among his front-bench colleagues. Then when Rudd and Gillard tacitly acknowledged the impact of this attack by postponing the scheme, he accused them of lacking the courage of their convictions. He’s right, but he’s also breathtakingly hypocritical.

On the ABC’s Four Corners six days out from the election, Marian Wilkinson put to Abbott that he disputed that humans have a role in current global warming. “Sure,” he agreed, adding “but that’s not really relevant at the moment”. He went on to say that “the only major political party with a credible policy in this area is the Coalition”.

So the claimant to the prime ministership says that when we consider what he’s going to do about our carbon emissions, it doesn’t matter that he thinks our emissions aren’t the cause of climate change. Why should we believe that “action man” will act on something he thinks is untrue?

Then there’s peak oil, after which the rate of oil extraction goes into a terminal decline. The US and UK governments both acknowledge that global peak oil has either happened or is soon to happen and that it will bring severe supply constraints and rising costs.

The Rudd-Gillard government all but ignored peak oil and its colossal implications, but it wasn’t so foolish as to deny its existence. Abbott feels no such constraint. A week ago he told a public forum: “The interesting thing about oil reserves is that they’re always being expanded,” adding that technology and price changes make reserves accessible that were once out of reach.

The major parties’ failure on climate action didn’t emerge into the surface fizz of this superficial campaign, but it remains as an underlying factor. The most obvious pointer is the strong outcome in both Houses for the Greens — the only party coming out of the election as a clear winner.

Then there’s the growing non-aligned vote, not least the astonishing Denison performance of Andrew Wilkie, whose policies acknowledge humanity’s role in climate change. The robust vote for independents, whatever their policies, is a clear sign of discontent with major parties.

The uncertainty over this election doesn’t end with the settlement of the numbers. Beyond that is a whole universe of doubt, about where the winners are going to take us over the next three years and beyond. And of all the big question-marks, climate and energy action is the daddy of them all.

This is what Professor Ross Garnaut had to say at the University of Melbourne earlier this month:

“The position on climate change is weak only because of an extraordinary failure of leadership. The failure is a product and represents the nadir of the early twenty first century political culture, in which short-term politics and accession to sectional pressures has held sway over leadership and analysis of the national interest. Those political advisers who turned out to have greatest influence over former Prime Minister Rudd weighed undoubtedly strong resistance from special interest groups, and inchoate reactions from partially informed members of the community, above more fundamental determinants of political success.”

With a will – and pressure from active citizens – there is the hope that Australia’s ‘balanced parliament’ will lead to reform of political practice to the point where the public interest once again is considered relevant, and not only the private and political interests of the powerful in our society; where focus groups and polling is replaced by careful and considered analysis; one-up-manship by consultation.