As the contrarian movement seeks to lull us to sleep with false reassurances, the IEA adds its voice to a rising tide of concern. [22 November 2011 | Peter Boyer]

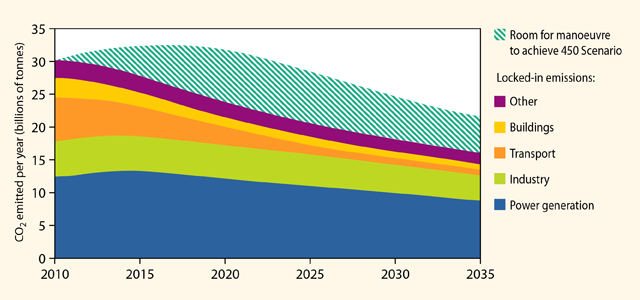

“THE DOOR IS CLOSING”: The IEA assessment of world energy-related CO2 emissions from locked-in infrastructure in 2010 and room for manoeuvre to achieve the 450 Scenario. Without further action, by 2017 all CO2 emissions permitted in the 450 Scenario will be “locked-in” by existing power plants, factories and buildings.

There’s an old-fashioned view that blokes and bedside stories don’t go together. Banish that thought. Telling bedside stories is something blokes do well when they put their minds to it.

The image that comes to mind is dad or granddad talking a fractious child to sleep at the end of a long day — a great thing to do that should be encouraged among our menfolk. But blokes also excel at another kind of bedside story.

This kind of tale is addressed to any adult who’ll listen, including the storyteller himself. It’s told at any hour of the day or night, but just like our stories to children its principal goal is to lull the listener into a mindless state where active thinking and questioning are suppressed.

In the “climate sceptic” fraternity — a testosterone-fuelled world where most gals know their place — there’s a comforting little bedside story doing the rounds that’s calculated to send us all into blissful slumber. There are numerous variants to the story, but here’s the gist of it:

The world is far too big for puny humans to have any impact on it. It changes as it always has, but we aren’t causing this and can do nothing to stop it. Sure we give off carbon dioxide but it’s just a trace gas in the atmosphere and it’s laughable to think it can make the world warmer.

The story gets murkier: there’s an unholy “green agenda” in which scientists, politicians, bureaucrats and green business interests spread untruths about climate (including through a corrupt peer-review process) to amass wealth and through the agency of the United Nations set up a world government.

But don’t worry, the story concludes. All we have to do to stop these schemers dead is to keep things are they are, to block any move to curb emissions and keep both the scientists and the UN in their place by starving them of funds. Simple.

The tale offers a soothing, soporific contrast to what it sees as “alarmism”, the sharply-worded warnings from the likes of the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s national science academies, and most recently — and quite surprisingly — the International Energy Agency.

Set up on the urging of the US government in the wake of the oil price shocks of the 1970s, the IEA’s key role at the outset was maintaining global energy security. In a world vulnerable to such energy shocks, it came to see this role in terms of smoothing troubled waters and soothing nerves.

Take for instance the issue of peak oil. It was only this year that the IEA explicitly acknowledged that global oil supply had indeed peaked, as long ago as 2006, and that we now had to adjust to steadily decreasing supplies.

Dr Fatih Birol, the International Energy Agency’s veteran chief economist, took it further, declaring that “the age of cheap oil is over” and advising everyone to get ready for higher prices and different “mobility habits”.

A changing world has brought a big shift in the way the IEA sees things. Moving well beyond a traditional focus on oil, it now looks increasingly at other energy sources and delivery mechanisms, such as its October report on renewable energy policy for a G-20 working group.

This month saw the release of the IEA’s flagship annual report, the “world energy outlook”. Focusing on the rising tide of carbon emissions, this year’s report is looking more than ever like the “alarmist” warnings that have so bothered the climate contrarians.

After trending down during the global financial crisis, the trajectory of global emissions suddenly jumped in 2010, the biggest rise on record, setting up a scenario that according to the IEA will see global warming and accompanying climate shifts become irreversible within a few short years.

Looking at current policies and planned infrastructure development over the next few decades, the IEA said there were enough new fossil-fuelled power stations and energy-inefficient buildings in the pipeline to make it impossible to keep emissions below the level needed to stop runaway warming, well above the 2C considered a safe limit.

Each year that passes without clear signals to drive clean energy investment, said Birol, was locking in high-carbon infrastructure and making it harder and more expensive to meet energy security and climate goals.

If the world did not curb this rate of development, by 2017 there would be no further room for manoeuvre. Enough energy-related infrastructure would then in place to generate the carbon dioxide emissions that would inevitably take temperatures beyond the safe limit.

“Delaying action is a false economy,” Birol said. “For every $1 of investment in cleaner technology that is avoided in the power sector before 2020, an additional $4.30 would need to be spent after 2020 to compensate for the increased emissions.”

Birol and the IEA might be accused of being alarmist, but the IEA’s cautious record would strongly suggest otherwise. They’ve chosen genuine science as their guide in preference to the bedtime story.

With the annual world climate meeting in Durban, South Africa, getting under way, we have to hope and pray that governments are alert enough to hear and heed these warnings.