It’s getting some stick from international airlines and governments, but the European court determination that airlines must pay for carbon emissions is a win for the planet. [10 January 2012 | Peter Boyer]

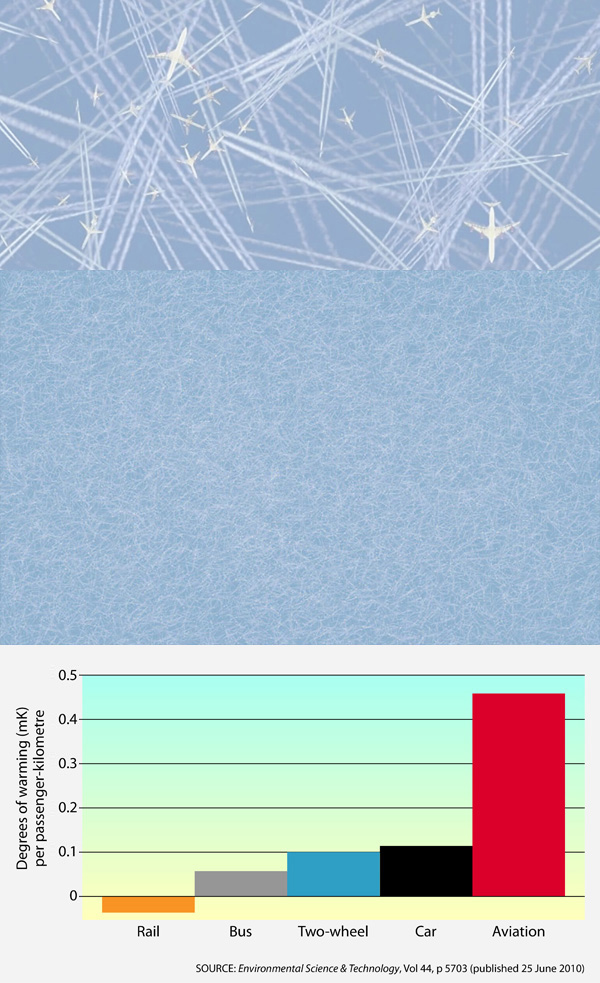

TOP TWO IMAGES: “Jet Trails” (2007), a 1.5m x 2.4m digital image by Chris Jordan (with detail above) depicting 11,000 jet trails, equal to the number of commercial flights in the US every eight hours. Water condensation trails, in addition to carbon dioxide and ozone, are a factor in aviation’s contribution to global warming. BOTTOM: Graph from a research paper published June 2010 showing the comparative short-term (5-year) impact on temperature of different forms of transport (based on year 2000 data).

Politics is the art of the possible, so the politicians tell us. They’re the ones who define what’s possible, so in the absence of adventurous leadership things happen very slowly, or not at all.

Climate policy is a good case in point. Science has found a mountain of reasons why we should act decisively to reduce carbon emissions, but politics has uncovered an equally big mountain of reasons why we shouldn’t.

The biggest obstacle to action is corporate or personal self-interest. If either big business or a sizeable chunk of the population is convinced that its well-being will suffer from emission-cutting measures, the politicians will tend to find reasons not to act.

So when personal and corporate self-interest are combined, you can rely on political leaders to bend over backwards to accommodate it, even to the extent of re-defining it as “national interest”.

That’s why, amid all the brouhaha around climate and energy policy, over the years international aviation has enjoyed a free ride (pun intended). Unlike land transport operators, carriers operating across national borders pay no tax on the fuel they put in their aircraft.

Until a few days ago they weren’t penalised for carbon emissions either. The aviation industry sees itself as a moderate carbon emitter, but it’s easily the most carbon-intensive way to transport people and freight, with a global carbon footprint that’s doubled since 1990 and may triple by 2020.

The short-term impact of aviation is even greater. A 2010 European study found that for five years after any given flight, the impact on global temperature of an airliner per passenger-kilometre is over four times that of the next worst offender, the car.

I think I’m on safe ground in saying most Australians will not feel comfortable knowing about this. Growing numbers of ordinary people are now able to afford the pleasure and reward of intercontinental travel. Who wants to curtail that?

Think, too, what’s at stake for professional people (including climate scientists attending regular international meetings, often many in a year), and the real movers and shakers, corporate high-fliers, politicians and bureaucrats, who like all of us love tripping to distant places. With such people as customers, the aviation industry has very powerful support where it counts.

This is all by way of background to a court’s decision in Europe last month that’s already ruffled some government and corporate feathers. Remember that Europe, despite its problems, remains a globally important economic power and the centre of world tourism.

In 2008, frustrated with global inaction over aviation emissions, Europe’s parliament decided to cap such emissions from 2012. As of now, every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted on a flight to, from and within Europe will require operators to surrender a permit (or “allowance”).

Operators must account for each year’s emissions and surrender the matching number of allowances to designated national authorities. They can determine how and where they reduce emissions by trading allowances within the European carbon market.

This seems perfectly fair and reasonable when you consider that other industries in Europe, under the European Union trading scheme, face similar penalties for carbon emissions. But the reaction from North America since the European laws were passed has been unremitting hostility.

US and Canadian airlines, with tacit support from their governments, took the EU to the European Court of Justice on the basis that the scheme violated international aviation agreements. After lengthy legal wrangling, only days before the law was to take effect the case was resolved in the EU’s favour.

The judges held that because the scheme applied only to aircraft within the EU and because non-EU airlines were free to choose not to land in EU airspace, the new regime did not infringe US or Canadian sovereignty.

As EU climate change commissioner Connie Hedegaard saw it, by engaging in the action the North American airlines accepted the rule of law. “So now we expect them to respect European law.”

The biggest non-European players in international aviation these days, the US and China, were predictably unhappy. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned of “appropriate action”, and China is reported to have blocked a planned purchase of new European-made Airbuses.

Clinton told EU President José Manuel Barosso that Europe could be isolated by its move, but given Europe’s pre-eminence as a destination that seems unlikely, as are the prospects of a US House of Representatives bill banning US airlines from complying with the EU scheme.

Infrastructure minister Anthony Albanese said last June he favoured an international system and thought the Europeans may have “got it wrong”, though the government has not responded to the European court decision. Australia’s new carbon pricing regime allows for adjustments to excise on domestic aviation fuel, but doesn’t apply to international air transport.

But Europe’s law provides for incoming flights to be exempt if the nation of origin has measures in place to offset international emissions. That suggests that it may be open for Australia to tweak its own carbon pricing scheme to allow exemption to Australians travelling to Europe.

Whatever that outcome, the European Commission estimates the per-passenger cost is likely to be less than 20 Euros. That’s not going to break anyone.