No-man’s land is a scary place, but it’s better than the trenches. [21 May 2013 | Peter Boyer]

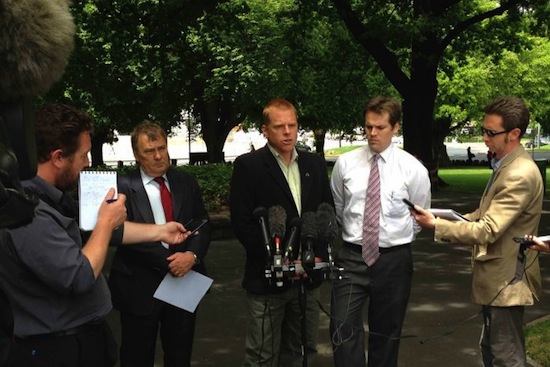

Vica Bayley (centre) and Phill Pullinger (right) front the media with Forest Industries Association representative Terry Edwards. ABC PHOTO

I don’t agree, said the novelist Richard Flanagan. We don’t either, said numerous others in angry blogs and letters to the editor. The Tasmanian Forests Agreement, whatever it does for our forests, has turned environmental comrades-in-arms into bitter enemies.

It was triggered by comments on 1 May from the Prime Minister, Julia Gillard. “Now the fringes of the debate need to fall away,” she said, adding that to calm the waters signatories on both sides needed to “silence” those opposing the mainstream consensus.

If Gillard had been closer to this conflict she may have chosen another word. “Silence” harks back to the 2004 Gunns legal action against forest protesters. But once the word was out, the fuse was lit.

Flanagan was quick to react. In a bristling assault on the agreement published on the Tasmanian Times website a few days later, he railed at environmental leaders for signing a deal seeking to silence Tasmanians’ rage against “the destruction of their land and the corruption of public life”.

The deal, he said, empowered a rogue government agency (Forestry Tasmania) and propped up “a dead forest industry” while locking in social conflict and political stagnation for another decade.

“I don’t give a damn for durability clauses and special councils of loggers and conservation police,” he fumed. “And I didn’t agree to be silenced, not by Paul Lennon, not by Gunns, and I won’t be now by The Wilderness Society and the ACF.”

The Australia Institute’s Richard Denniss went further, implying that Gillard was acting on advice from the conservationists backing the deal. “It is quite clear why the environment groups involved want to silence protest,” he said. “They know their deal doesn’t bear scrutiny.”

Parliament’s passing of the agreement bill set off a raging argument within environmentalist ranks, focused mainly on key negotiators Phill Pullinger (Environment Tasmania) and Vica Bayley (The Wilderness Society), along with the Green MPs who voted for the agreement legislation.

Former Tasmanian Greens leader Peg Putt, now heading the forest lobby group Markets for Change, castigated the negotiators for trusting the word of Forestry Tasmania — “not something any clear thinking environmentalist would put faith in at the best of times”.

Jenny Weber of the Huon Environment Centre saw the negotiators as “the green-mouthpiece for a forest industry.” They and the Green MPs who supported them, according to tree-sitter Miranda Gibson, had “aligned themselves with the collapsing forestry industry at the expense of our forests”.

Others went further. “Greens suck and are no friends of conservationists,” said one. The negotiators and the four assenting Greens MPs were revisionists and appeasers, “rusted-on Greens”, “willing pawns” and “witless fools”. This on a moderated blogsite!

A few things need to be said about all this. The three negotiating environmental groups did not agree to “silence” anyone. They were involved in the agreement as representatives of their own organisations and never asserted any rights over non-participating groups.

In entering the negotiations all those years ago, the three groups were opening themselves to compromise while investing trust in the process and in the goodwill of opposing negotiators. This is as it must be. It’s what negotiated outcomes require, every time, without exception.

I know three of the four main environmentalist signatories, Bayley, Pullinger and Don Henry of the Australian Conservation Foundation. (The other was Lyndon Schneiders, national director of the Wilderness Society.) I believe they are astute and exacting negotiators whose credentials and commitment are incontestable, and that the invective heaped on them is unfair and unfounded.

Deliberately or not, conservationist opponents of the deal have ignored what Bayley, Pullinger and Henry knew all too well, that negotiation involves venturing out of the trenches into no man’s land.

This is a tough lesson for anyone who has grown close to an issue and feels threatened by perceived opposition or indifference in the wider world. That includes me. I’ve done my share of ranting about our collective failure to wake up to what’s happening to the climate.

Seeing Bill McKibben’s new movie, Do the Math, has done little to calm the nerves. Having committed to contain global warming to 2C, says McKibben, the world’s governments collude with rogue fossil-fuel interests committed to burning enough coal and oil to heat the world to above 5C.

This is bad enough, but as McKibben points out we’re now locking ourselves into acquiring fuels from non-conventional sources, such as oil from tar sands and gas from coal seams, that extend the problem out into uncharted territory.

McKibben has made the not-so-funny suggestion that perhaps, instead of naming cyclones after innocent people like Sandy, Katrina and Larry, we name them after fossil fuel companies. Hurricane Exxon or Cyclone Peabody have a certain ring to them, don’t you think?

But governments aren’t going to treat fossil fuel companies as rogue industries or invoke corporate wrath by allowing storms to be named after them. They just don’t do those things and it’s disingenuous to pretend otherwise. I wish they would, which is why, like Flanagan, I’m often irritated by politics.

There’s plenty of reason to rage about the failure of this or that government or minister to “get it”. In the sorry saga of humanity’s response to global warming, governments’ missteps, missed opportunities and mistakes are legion.

But in the end we have to stop raging and start doing. That must include publicly demonstrating our dissatisfaction with authority, but it must also include contact with that authority and acknowledgment that a small step forward is better than none at all.

We’re all in this together. Self-righteous sermons can be a buzz, but real advances will only be won through engagement.