An Abbott win on Saturday signals danger for Australia’s hard-won carbon price. [3 September 2013 | Peter Boyer]

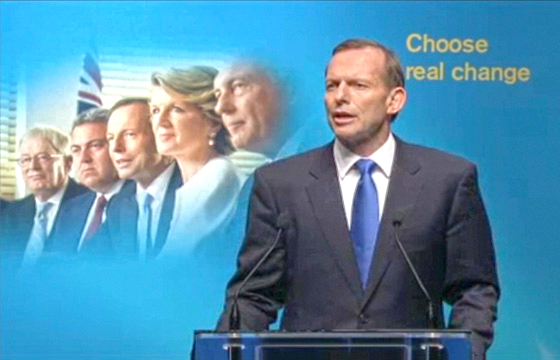

Tony Abbott delivers his policy speech at the Liberal Party campaign launch. PHOTO ABC

Here’s the message about climate change from Tony Abbott’s campaign launch at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre on August 25.

Did you catch it? That’s right — the prime minister-in-waiting didn’t give climate a single mention in his 13-minute policy speech. But he did mention the carbon tax, several times. He promised that legislation to repeal it would be before Parliament within 100 days of the election.

Kevin Rudd, he said, “knows that the carbon tax has been a disaster — that’s why he’s faked abolishing it.” He was referring to Rudd’s plan, announced six weeks ago, to “terminate” the carbon tax by making the transition to emissions trading next July, a year ahead of schedule.

As if to underline Abbott’s take on Julia Gillard’s carbon pricing scheme, on the day of the Liberal campaign launch Rudd told ABC’s Insiders that a carbon tax was one of the things Labor had got wrong, partly because “we didn’t have a mandate for it”.

Terminology carries its own message. Abbott made “carbon tax” a derogatory term, such that Rudd felt he had to “terminate” it. The message from all that is that the scheme so painstakingly wrought by Labor, the Greens and independents Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott was a wrong turn.

But for many Australians this notion is puzzling. A price on carbon, whether fixed (like a tax) or floating (a market price), seems a good way to cut emissions. Were the Clean Energy laws a false step? This is a money matter, so it seems reasonable to seek economic advice.

ANU economics professor Warwick McKibbin is a long-standing critic of both the present tax scheme and its floating-price successor. He’s devised a scheme of his own involving both fixed-price single-year permits and tradable multi-year permits with an overall emissions cap.

I’m not able to judge whether McKibbin’s system is better than what we now have in place, which is based on the thinking of another economics professor, Ross Garnaut. Like scientists, economists love to argue among themselves.

But like the scientific agreement on the impact of man-made carbon in the air, there’s an underlying accord in the economic debate. McKibbin wrote recently that economists are in “nearly universal agreement” that a price on carbon is “highly desirable” to reduce the risk of climatic disruption.

If the Coalition’s anti-carbon pricing policy flies in the face of current economic wisdom, that’s not surprising. Abbott’s view was shaped not by economics but by politics, first by his party’s internal wrangling over Rudd’s scheme in 2009 and then by his anti-Gillard campaign to “axe the tax”.

But with Abbott odds-on to take the helm next weekend, perhaps with a Senate majority, this is where we’re headed. There are implications not just for Australia but for the whole world.

Labor in opposition may feel compelled to concede a Coalition mandate to end the scheme and vote in favour of Abbott’s legislation to ditch it. Alternatively, if Abbott doesn’t control the Senate Labor may decide to defy him and side with the Greens to force a double dissolution election.

Such an election would effectively be a referendum on whether we should put a price on carbon. This would present some risk for an Abbott government. The vote wouldn’t be for at least a year; by then most may want to keep our carbon price and be prepared to change government to do so.

Even so, it’s distinctly possible that by 2015 the Australian carbon price will be history.

I’m not one of those who thinks that the market can solve everything. A failed market can cause great damage, at huge cost to the general public. But in this case I see every reason to side with the majority of economists and support the present fixed-cum-floating price system.

Bookends: ABOVE Julia Gillard shakes hands with Greens leader Bob Brown, watched by her deputy Wayne Swan and Green MPs and senators, 11 days after the 2010 election [Alan Porritt/AAP]; BELOW Rob Oakeshott’s farewell to the House of Representatives after Gillard was deposed in June 2013

The present scheme was also hard work, stemming in part from the firestorm around Julia Gillard’s 2010 campaign statement, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead, but let me be clear: I will be putting a price on carbon and I will move to an emissions trading scheme.”

Actually, the Clean Energy laws turned out to be close to what she said. All those who negotiated the package, including the prime minister, knew they risked their reputations on the outcome, but they were convinced that it was worth the effort. And it was. They’re right to be proud of it.

The scheme’s integrated components include the Climate Change Authority, the Clean Energy Regulator, the Clean Technology Program, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency. They were all good ideas. All are worth keeping.

But the scheme as a whole is bigger than the sum of its parts. The passage of the legislation in 2011 put a global spotlight on Australia, where it remains, highlighting to the world that this country is prepared to make an effort to curtail its carbon emissions.

And just as the significance of our carbon pricing laws crossed national borders, so is it crossing to the next generation of Australians, telling them that we care about their inheritance. That message will be lost if the parliament does as Abbott wants and repeals these laws at the first opportunity.

Australia can hold its head high for having managed to put a price on carbon pollution. The system has flaws because it’s big, it’s new territory and it involves many competing interests. But over time the flaws can be repaired through amending legislation. That’s what we have parliaments for.

Instead, Australia is being asked to discard its hard-won carbon price and replace it with something that the leader-in-waiting didn’t see fit to mention in his policy speech. We deserve better.