The government’s budget is threatening an 88-year-old covenant between government and science. [20 May 2014 | Peter Boyer]

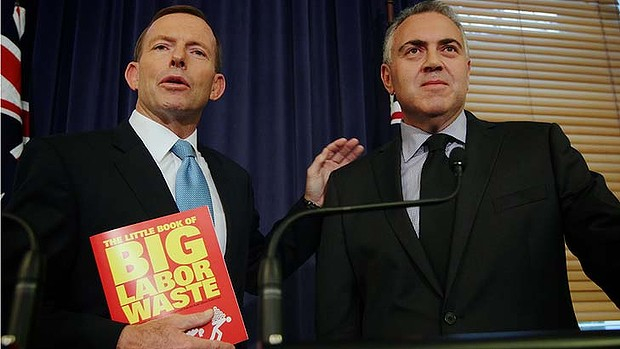

Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey discussing another government’s budget problems, a year before Joe Hockey delivered his own 2014 budget. PHOTO FAIRFAX MEDIA / ALEX ELLINGHAUSEN

Polls, talkback radio, letters to the editor… everywhere the message is the same. The first Abbott-Hockey budget was supposed to start pulling things together. Instead they’re falling further apart.

Politicians of all persuasions devote an inordinate amount of energy to self-image and pretence. Kevin Rudd pretended he could control everything: a fast track to disaster. Wayne Swan and his treasury pretended against mounting evidence that a 2013 surplus was achievable.

Tony Abbott and his shadow ministry pretended we could have our cake and eat it too, as if they were masters of the universe. Now, the masters of the universe are copping the sort of backlash that’s led past governments to change direction. But I wouldn’t bet on that happening.

This is no normal government, and Abbott is no normal leader. When Australians elected him to office in September he was understood to be a focused man with some very strongly-held beliefs, but few would have anticipated the small-government revolution that he’s now set in train.

We’ve heard a lot about the social and personal consequences of a budget driven solely (so we’re told) by a desire to get the nation’s finances back into the black, to fight and conquer the “debt and deficit disaster” which the government says it inherited from Labor.

In the debate about how this radical budget affects the young, the elderly, the poor, the sick and the unemployed, not to mention students and the arts, another target of government cost-cutting hasn’t had the airing it deserves.

It was known Abbott would cut government jobs, though 16,500 terminations are a lot more than indicated before the election. It’s instructive that the biggest loser (4500 jobs) will be our tax regulator, the Australian Tax Office, a move that’s certain to please business.

Less well-known is the impact that his small-government drive is having on science in Australia.

This budget will be remembered for many things, but prominent among them will be its clear signal that the Abbott government is intent on putting paid to an 88-year-old covenant between science and government which has made Australian research a beacon for the world.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) has been the main embodiment of our nation’s commitment to world-leading science since it was founded in 1926 under the arch-conservative Bruce government.

A long record of advanced research in physics, chemistry, global systems, astronomy, agriculture, plant science, information science and computer modelling has given it an enviable profile. It’s now one of the world’s best-known and respected scientific institutions, the pride of the nation.

The CSIRO expects to feel pain when belts are to be tightened, but it’s starting from a low base. After the Howard government’s big cuts in the late 1990s came a recent restructure that has seen 300 more positions cut. By any standards this is a very lean government agency.

The Abbott government has wasted no time in targeting another 500 CSIRO positions, of which 420 are to be gone by mid-2015. The organisation’s CEO, Megan Clark, spoke last week of “painful” times for CSIRO people “who have dedicated themselves to the future of Australia”.

Tasmania will feel the job losses keenly. The scientific programs of CSIRO’s Marine and Atmospheric Division, as well as the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) and the University of Tasmania, contribute significantly not just to global knowledge but also to the state’s economy

Post-budget publicity tells us that the AAD will benefit from extra government funding for its shipping and air transport operations. There’s been no public discussion of job losses, but I’m reliably informed that scientific positions will go there too, as many as one in every five.

Some scientists have already had their marching orders, but the layoffs won’t start in earnest for some months. Tony Abbott’s war on science is in that awkward early phase that you see in all conflicts, the phoney war before the mayhem begins.

We need science. Not just in the broad, undefined way that helped shape our country and civilisation, but also as a specific tool for government. Science has been especially valuable as a guide, for Australia and the rest of the world, in navigating the tricky climate path ahead.

Two months before he won Liberal leadership in 2009, Abbott told a country audience that the scientific argument that humans were causing climate to change was “absolute crap”. That remark showed a disdain for the processes that led to that conclusion, and for the scientific method itself.

In government, on the subject of human-caused climate change Abbott is mute because he doesn’t want to be seen to be out of step with his party’s official policy to cut emissions. But there’s every sign that he continues to believe that the science behind it has no place in political decisions.

In 2011 he watched in angry frustration as MPs Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott, sitting in seats he regarded as the Coalition’s by right, voted to allow passage of the Gillard alliance’s carbon abatement measures, which were guided in turn by government-supported science.

He doesn’t forget such things. Now that he’s in charge, these measures and all who’ve been associated with them, including the wider scientific community, are in the government’s crosshairs.

The coming sackings of scientists aren’t driven by intellectual or budgetary considerations, but by something more personal and more visceral: resentment and revenge. This isn’t a war of ideas but of atonement, a crusade against the infidels with the prime minister leading the charge.

• “The Clean Energy Tipping Point” (6pm Tuesday May 27, UTAS Stanley Burbury Theatre, Sandy Bay), is a public discussion about the shift already underway from fossil fuels to renewable energy, led by Giles Parkinson of RenewEconomy and global sustainability authority Paul Gilding.