Amid all the world’s trouble and strife, Christmas is still something to celebrate. [23 December 2014 | Peter Boyer]

A century ago tomorrow evening, the noise of gunfire along a small part of Europe’s Western Front suddenly stopped. The “war to end wars” was just four months old.

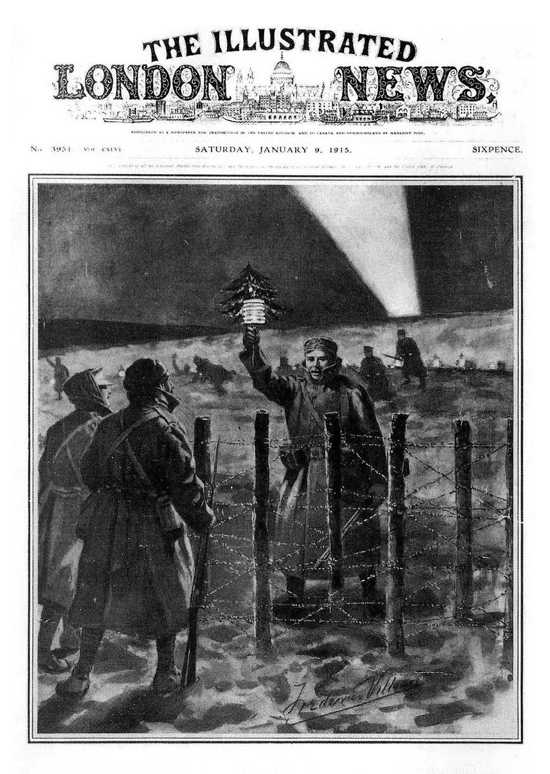

News of the Christmas truce took two weeks to reach the popular media such as The Illustrated London News. The original caption of this picture read: “The Light of Peace in the trenches on Christmas Eve: A German soldier opens the spontaneous truce by approaching the British lines with a small Christmas tree.”

On a freezing, windless Christmas Eve, defying standing orders to maintain hostilities, German, British and French troops climbed out of their trenches to exchange friendly greetings, sing carols and bury their dead.

The spontaneous action that brought a moment of peace to the trenches happened despite governments’ rejection of Pope Benedict XV’s plea a fortnight earlier “that the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang”.

Other brief ceasefires happened during the war, including at Gallipoli where the enemy was Muslim, mainly to retrieve and bury the dead. But the Christmas truce was something special.

In a few pockets along the 700 km front the ceasefire lasted for a week, ending only when soldiers on both sides were told that if they didn’t resume hostilities they could be charged with mutiny.

Had that respite extended into a longer truce and attracted more soldiers, who knows, we might have been spared the appalling carnage of the years that followed. But the men were coerced back to their deadly work, and Christmas was over.

The sense of desolation at the war’s end was widespread and intense. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”, lamented the Irish poet WB Yeats in 1919. In Yeats’s post-apocalyptic world, “the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity”.

In Christian tradition Jesus is to return to Earth in glory to judge mankind. Yeats imagined this second coming as a “rough beast” awakened from “twenty centuries of stony sleep”. In our own troubled times 100 years on, his dark vision carries a ring of authenticity.

But the spirit of that Christmas truce lingers. Benedict and the errant soldiers bring to mind music from my time as a child chorister in our local Anglican church. “It came upon the midnight clear” was a favourite hymn of mine. The lines were written in 1849 by an American, Edmund Sears.

There is a verse lamenting war, “O hush the noise, ye men of strife, and hear the angels sing”, invoking the same image of heavenly choirs that Benedict employed. In those times of conflict it resonated powerfully.

It still does, with me at least. I’m no longer a believer, but there’s a part of me that continues to find value and solace in Christmas messages of peace and goodwill. The angels are unreal, just a metaphor really, but I still feel the power of that image and the words and music around it.

Christmas is a deeply human event. Its thoroughly earthly qualities predate Jesus by millennia. The returning of the light after the December solstice, the time of greatest darkness in the north, has been celebrated since humans first gazed skyward.

The Christians added their own celebration and claimed the time as their own, the inevitable result of believing that your god is the one true God. The Muslims believe the same of theirs, as do the Jews. They can’t all be right. Or perhaps they are, and just haven’t learned to share.

Jesus has a foot in all camps. He was born a Jew, anointed Son of God by the Christians and is integral to the teachings of the Quran. Historians agree he actually existed, but eyewitness accounts of his life are fragmentary, only serving to make him more fascinating.

We can be reasonably sure that Jesus was baptised, that he argued about God with other Jews, that in Galilee he had a following of both men and women, and that his life ended when Roman soldiers crucified him near Jerusalem some time before AD36.

In itself this short life made the smallest of marks in history, but the subsequent impact of teachings ascribed to Jesus looms over world history like a colossus, a determining influence on Western thinking. Whatever our religious disposition, there’s a Jesus factor embedded in it.

The New Testament spawned Christian institutions that have failed us and Christian enmities and schisms marked by ignorance, injustice and atrocity. It also softened the hard edges of the Old Testament and gave form to our concepts of justice, equity, mercy and forgiveness.

As for Christmas, the silent, holy night in no-man’s land has given way today to commercial excess and household budgetary problems we can do without. The best part of Christmas, the company of those nearest to us, doesn’t carry a price tag.

On Thursday, the pagan in me will celebrate the glories of summer and the returning darkness (I’m a man for all seasons). But I’ll also celebrate the Nazarene’s 2000-year legacy, and the spirit of Christmas that in a remarkable moment 100 years ago brought the angels’ songs to a battlefield.

May your day be happy and peaceful.