Greg Hunt claims a “stunning” success for the ERF, but it’s far too early to tell [28 April 2015 | Peter Boyer]

Remember Tony Abbott’s 2013 line about carbon trading – “a so-called market in the non-delivery of an invisible substance to no-one”? Well, last week he put $660 million into exactly that.

He won’t ever admit it, but his government’s Emissions Reduction Fund is a market for greenhouse gas emissions and now it has its very own carbon price. Whether it will work is yet to be determined.

Environment minister Greg Hunt thinks it will. In fact he believes it’s the way for the future, “a plan for the next half century” as he told ABC Radio National last week.

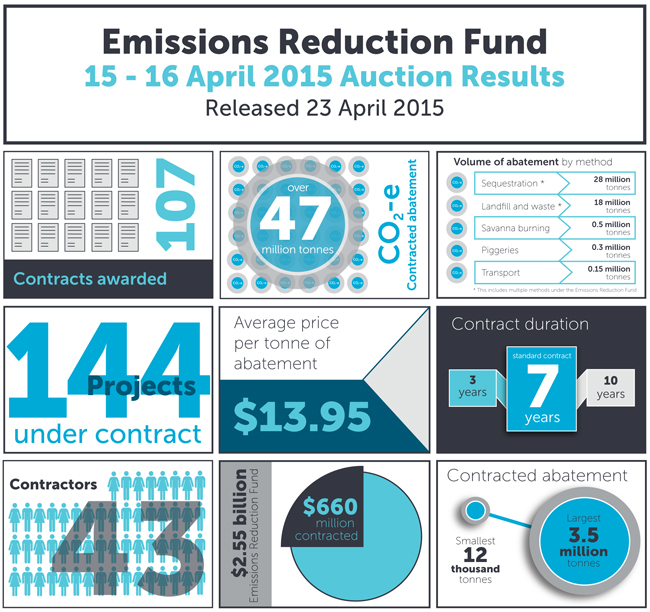

Successful bids for the first ERF auction, announced last week, realised an average price of $13.95 a tonne. Most of the money will go to growing trees and dealing with gas from landfill. The big emitters, in mining, metallurgy and stationary and transport energy, are yet to join in.

The money will be paid as the 144 projects deliver their promised emissions reductions, totalling 47.3 million tonnes. Under most contracts, final payments won’t be made until 2025.

Just ahead of the ERF announcement Hunt said that he thought five million tonnes of purchased abatement would be an “outstanding” result. On cue, when the much higher figure came in a few hours later he described it as a “stunning” success that “will reverberate around the world”.

Australia’s first carbon price scheme, known as the carbon tax, was terminated long ago by the Abbott government, but you wouldn’t have thought so at Hunt’s post-auction media interviews, so prominently did it figure in his responses to questions.

There’s been persistent criticism from economists that the ERF is expensive and will get more so. Asked about funding the ERF beyond the forward estimates, Hunt made the astonishing claim that its cost per tonne of emissions saved was about a hundredth that of the carbon tax.

What Hunt chose not to mention or factor into his calculations is that the cost of Labor’s scheme was balanced by its own permanent revenue source, a specific levy on pollution. The ERF has no such income stream, which makes its long-term cost a big issue.

As major players including the US and Europe ramp up their commitments, pressure is coming on Australia to come up with a strong post-2020 target. If the ERF is to be the principal abatement instrument, the call on revenue is bound to rise, perhaps steeply.

That wouldn’t be good news for treasurer Joe Hockey, nor for Tony Abbott, who has firmly stated that the $2.55 billion allocated to the ERF is all it’s going to get, period. More than a quarter of that money, $660 million, has already gone with the first auction.

Hunt airily dismissed such concerns. He said the auction confirmed that “we’ll breeze past our target for 2020 and be in a position to make real and significant cuts beyond that”.

Hunt’s department released projections just last month putting the abatement required to meet the 2020 target at 236 million tonnes, but the minister thinks the real figure is much lower than that and “dropping all the time”. There’s evidence for this, but it warrants closer scrutiny.

Hunt nominated declining coal, manufacturing and agricultural production and electricity demand as causing the drop. He should also have mentioned a successful large-scale renewable energy target (which the government wants to cut) and rapid domestic take-up of rooftop solar.

Australia’s already-easy 2020 target – five per cent below 2000 emissions – is getting easier because of external forces and can’t be attributed to any Abbott government policy innovation.

Given that and the growing pressure to perform post-2020, the smart thing to do would be to set a strong longer-term target. The Climate Change Authority advises a 2025 target of 30 per cent below a 2000 base, but the government won’t listen to a body it wants to disappear.

Emissions in 2005 were nearly 7 per cent above those in 2000. Hunt exploits public ignorance of this by expressing the 2020 goal against 2005 emissions, thereby boosting our tiny target to a more respectable 13 per cent. I’m betting the government will do the same for its post-2020 target.

Hunt claimed instant success for the ERF last week, but just as it was for the carbon tax, it will be years before we can really know. We do know that the scheme won’t succeed without public confidence, and that can’t happen when truth is obscured by ministerial sleight-of-hand.

Hunt is getting away with it because climate remains unfamiliar territory to many journalists, lacking the detailed knowledge to ask the critical questions. Politicians and journalists alike will have to do better.