The government looks the goods on terrorism, but climate change presents a much bigger challenge. [30 June 2015 | Peter Boyer]

When federal parliament voted last week to cut by 20 per cent the amount of clean energy it aims to have in 2020, Australia became the first country in the world to cut back a climate target.

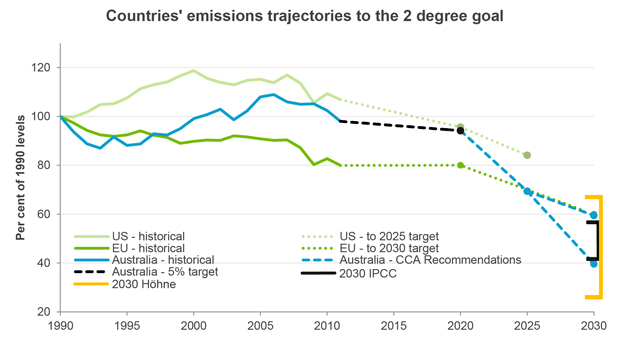

The Climate Change Authority’s plot of Australia’s emissions trajectory to the 2C goal (blue line; black for the period to 2020), compared with the United States (pale green) and Europe (deep green). The black and orange bars at the right indicate different estimates of the global reduction needed to reach 2C of warming above pre-industrial levels. Note that the dotted black line is nearly flat, due to lower emissions resulting from less electricity usage and an economic slowdown. A stronger 2020 target would have made the dotted blue line beyond that less steep. SOURCE: Climate Change Authority (April 2015): Australia’s future emissions reduction targets, Fig. 7

This has never been done before under any jurisdiction – not even in North America, home of climate denial. That’s on top of us becoming the first country to abolish a carbon pricing regime in June last year. Who says Australia can’t be a world leader?

Another world first: the bill to cut the renewable energy target also empowered the government to appoint a wind farm commissioner to check out complaints that wind turbines make people sick.

This is despite two studies by the National Health and Medical Research Council, in 2009 and again last year, that found no evidence linking wind turbines and poor health. At least two state investigations and numerous overseas ones have reached the same conclusion.

The Renewable Energy Target changes may not do much damage. The delayed outcome caused uncertainty about investing in major projects, especially wind farms, but rooftop solar continues to make inroads into the electricity market. Market momentum in Australia and globally is all on the side of renewables.

That sorted, the government now faces the big decision. Australia’s post-2020 emissions target will identify how much effort we’re prepared to put in to keep global warming below 2C above pre-industrial levels, which we and the rest of the world signed up to in 2010.

CSIRO, the Bureau of Meteorology and all other major scientific institutions, and global authorities in energy economics including the World Bank and the International Energy Agency, say that if we don’t cut emissions deeply now we face stupendous costs in coming decades.

Multiple international studies have concluded that developed countries, taken together, must halve emissions by 2030 to give the world an even chance of staying below the 2C limit. On that basis, Australia’s Climate Change Authority recommends a 2030 target of between 40 and 60 per cent. It also recommends a target for 2025, just 10 years away, of at least 30 per cent, a long way above our present 5 per cent.

So how will our leaders respond to this significant challenge?

Leadership is currently in short supply. Last week, opposition leader Bill Shorten had a leadership moment when asked if Labor would continue to fund the Gonski school reforms, arguably the most important educational advance in all our lifetimes. He failed that test, spectacularly.

His party is trying harder with climate change. Its Environment Action Network will push at the July national conference for a target of 50 per cent lower emissions by 2030. The Greens have gone further, backing 40-50 per cent by 2025, 60-80 per cent by 2030 and net-zero by 2040.

These targets are based on Australia’s emissions in 2000, about 560 megatonnes. Five years later, with the minerals boom in full swing, they’d jumped by 50 megatonnes. Five per cent below 2000 emissions is 13 per cent below 2005. The outcome is the same, but the latter looks much better.

The government has already started its window-dressing in preparation for announcing its target in mid-July. Environment minister Greg Hunt has begun expressing our measly 2020 target in terms of the more flattering 2005 baseline.

The government won’t accept advice from the Climate Change Authority, which it has tried and failed to abolish. Instead, the prime minister’s department is doing its own investigation.

Don’t expect the physical imperatives of climate change, including the fast-vanishing prospect of limiting warming to 2C, to figure in this inquiry. When the department called for public submissions in March it signalled that it would be focusing on economic growth and trade.

Progress in reaching the 2020 target seems to be due mainly to what market analyst RepuTex calls “systemically overstated” official emissions figures. It says that lower export growth and electricity demand are likely to shave 200 million tonnes off emissions currently projected up to 2020.

All this may look good domestically but spells trouble for Australia at the Paris meeting in December. As RepuTex sees it, “Australia risks being perceived as pocketing the benefit of its own error, and therefore not fairly contributing to the international emissions reduction effort.”

Being strong on national security is one way to look like a leader. The government’s focus on protecting borders and banishing jihadists resonates when terrorism is in the headlines.

Climate change, demanding substantive, transformative actions that will determine our country’s long-term future, is a much tougher issue than the threat from terrorism. But that’s the kind of challenge real leadership thrives on.