There’s a good chance that climate policy will determine the next election, but unfortunately Lisa Singh won’t get the reward she deserves. [28 July 2015 | Peter Boyer]

The complaint at the weekend about Labor’s recharged climate policy, that we can’t afford it and are too small to matter anyway, was as predictable as it was wrong.

Global warming is happening faster than anyone predicted. This month the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration revealed that Earth was even warmer at its surface in the first half of 2015 than in the same period last year, the warmest on record.

Last week a research paper by a large team of world-leading scientists said that the current international warming limit of 2C above the preindustrial level was “highly dangerous”. The study, led by veteran climatologist James Hansen, concluded that continued warming of deep-ocean waters resulting from today’s high-emission trajectory would probably cause “large scale ice sheet disintegration”.

Every day, new scientific findings add new urgency to calls for deep cuts in global emissions within a few years, and for all the world’s major and mid-level nations, including Australia, to get to work to decarbonise their economies. Yet we keep hearing it’s too expensive.

But what would be the cost of hundreds of millions of coastal-dwelling people being displaced and coastal infrastructure destroyed if events turn out as the Hansen paper asserts: that “multi-metre sea level rise [is] practically unavoidable and likely to occur this century”?

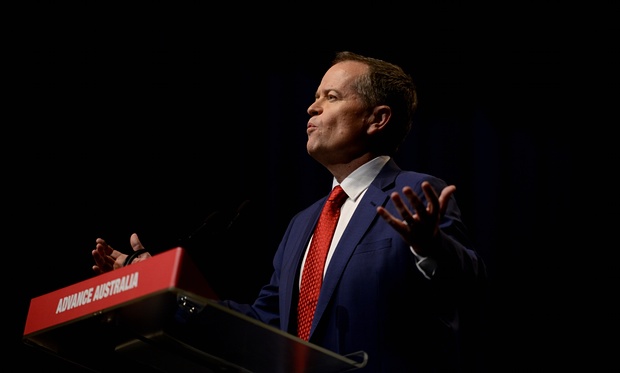

Against this backdrop, at his party’s national conference on Friday Bill Shorten said a Labor government would have renewables generating half Australia’s electricity by 2030.

The ambitious target, said Shorten, would see more solar panels on Australian rooftops, more high-tech batteries storing solar power, more wind turbines on farmland and more support for a sector expected to attract $2.5 trillion in investment in the Asia-Pacific region in the next 15 years.

Having seen Labor’s two previous carbon pricing schemes bite the dust, Shorten has yet again put the “market solution” of emissions trading back on the table, tapping into a global market of “a billion people and more than 40 per cent of the world’s economy”.

A defiant Shorten said his party would not be intimidated by “ignorant, ridiculous scare campaigns”, declaring “we will win this fight.”

There’s a lot still missing here. We don’t know how Shorten plans to get solar, wind, wave, tidal and other renewable energy technologies up to the scale required to meet the target.

And Labor still hasn’t had its say about post-2020 national emissions targets. If it follows the lead of its own Environment Action Nework it will support the Climate Change Authority’s recommended targets of 30 per cent below 2000 levels by 2025 and 40 to 60 per cent by 2030.

A Labor emissions policy couldn’t rely on lower electricity demand, as the present government has done in pursuit of a 5 per cent emissions reduction target. The 2030 targets will demand multiple measures to deliver big cuts to fossil fuel use.

Labor is staking a claim to represent people genuinely concerned about climate action, but all this is still just talk. Apart from the small matter of winning government, the party has a distance to travel before Australians can feel confident that this is a credible position.

The party would have more credibility had it found a way to retain the services of a true climate champion, Tasmanian Senator Lisa Singh. Instead it has relegated the party’s climate spokesperson in the Senate to an unwinnable position on the ballot paper for next year’s election.

Union legend Bill Kelty wanted the national conference to get rid of the undemocratic rule that gives unions extra voting power to get their chosen people into office regardless of the performance of sitting senators, but not even he could sway his colleagues.

So Singh will be forced out after just one term. She will be especially peeved if the big global issues she’s been wrestling with turn out to be front and centre in the next election.

But that’s just what looks like happening. With climate firmly on Australia’s political agenda, policies to cut carbon emissions may actually determine our next government. That would be a welcome development.