Our own economic future is being compromised by our failure to join the heavy lifting on climate policy. [18 August 2015 | Peter Boyer]

All things are relative, and carbon emissions targets are no exception. What we think of Australia’s 2030 target depends on which countries we choose to compare it with.

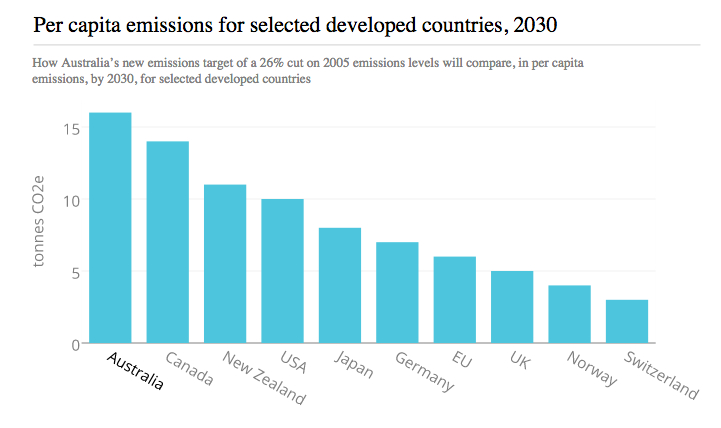

The government has claimed the biggest cut in per-capita emissions by 2030 of any country, but that still leaves us well above any other developed country, as this Guardian Australia graphic shows.

Last week Tony Abbott singled out Japan, Korea and China for special mention when pointing out that his government’s 2030 target – 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels – was above theirs.

He’s right about that. Korea’s elusive target, based on rubbery “business-as-usual” forecasts, is inadequate whichever way you look at it. Japan has opted for a cut of just 25 per cent by 2030 while China’s goal is actually a 150 per cent increase.

But both the latter two can claim special dispensation. Japan has had the double challenge of chronic recession and the ongoing Fukushima disaster, and China seeks to develop its economy in a quarter the time it took us. In both cases, ambitious emissions targets could threaten social stability.

Australia’s target looks good in that company, but it’s notable that the government has been more evasive about the countries we see as most like us: New Zealand, Canada and the US, and especially western Europe. Those comparisons aren’t so flattering.

The US has the same figure as Australia but with a deadline five-years earlier, plus a longer-term target that will require a cut of about 40 per cent by 2030. Across the ditch, New Zealand has set itself a target of 30 per cent below its 2005 level, 2 to 4 per cent better than Australia’s.

Canada has set the same 2030 target as New Zealand, which is a surprise. Stephen Harper’s fossil-fuelled government has for many years stridently opposed reining in carbon emissions. The new target is likely to require some tough decisions about Alberta tar sands.

Then there’s the gold standard, Europe.

In the 1990s western European countries were more alert than most, including Australia, to the need to transform their energy economies. The heavy lifting they did then might have enticed them to go easy today, but they’ve opted instead for even more ambitious targets.

Germany’s target requires emissions in 2030 to be 46 per cent below their level in 2005, while the United Kingdom has gone further, 48 per cent down by 2030. Most ambitious is Switzerland, pursuing a cut of 50 per cent over the same time span.

There’s nothing especially honourable in this. These governments have strong targets largely because a healthy majority of their electors want it that way.

And it works. Previous strong European targets fostered extraordinary effort to improve energy efficiency and roll out solar, wind, wave, tidal and biomass power. Many targets were reached with room to spare. The result is a continent far better prepared than Australia for a low-carbon future.

We took a different route. At the Kyoto climate talks in 1997, while European countries were knuckling down to cutting emissions, Australia campaigned successfully for an escape clause in the agreement that allowed it to raise fossil-fuel emissions by 8 per cent.

That “Australia clause”, as it’s known around the world, is the basis of the common claim that while others have failed, Australia met and surpassed its Kyoto targets. Like shifting base years and so much else around climate policy, this is pure political spin.

Government modelling appears to confirm that a 45 per cent 2030 target would lower Australia’s GDP by, at most, 0.7 per cent. We can afford to do much more. In fact we can’t afford not to.

Europe and increasingly the rest of the world recognise that developing clean energy while phasing out fossil fuels is more than a scientific imperative; it’s also an economic necessity. Countries choosing to defy that reality are seriously compromising their own economic future.

Public events

HEALTH, wildfire and coastal experts will discuss the ups and downs of Tasmania’s climate future at Climate Tasmania’s free public forum on Monday at Aurora Theatre, IMAS Building, Salamanca Place, Hobart, from 5.30pm.

WINGS of the Sun, a film about the world’s first overnight solar-powered flight, will be a special Science Week event starting at 6pm on Sunday (University of Tasmania’s Stanley Burbury Theatre, Sandy Bay). Entry by gold coin donation.