Professional journalism has never faced challenges like today’s, and we have never needed it more.

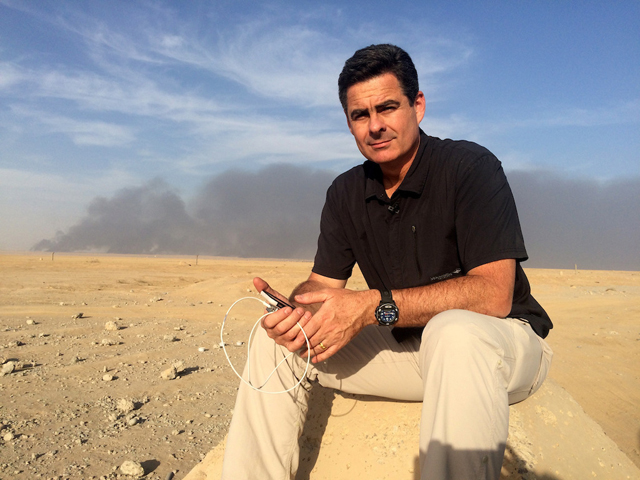

ABC Middle East correspondent Matt Brown reporting from Mosul. PHOTO ABC

If only one Australian was left unmoved by seeing Jacqui Lambie say goodbye to the Senate last week, or Penny Wong hear the news that Australians support her right to marry, I’d lay odds it was a journalist.

There’s something inhuman about the profession. People function by being part of the business of humanity, but journalists are expected to be outside that circle, observing without getting involved. That is fertile ground for cynicism.

I refer to journalism as we once knew or imagined it to be. That is, reporting for a newspaper, broadcaster or digital outlet whose authority rests on ethics-based public-interest journalism, of the kind I grew up with, before I strayed into other things.

I’m definitely not saying that journalism has gone downhill. The best of today’s crop are as good and as dedicated as any I rubbed shoulders with, and far better informed about the wider world. They also carry a greater burden.

Judged by revenue, volume of output and numbers participating, Google, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and the like are today’s big global news organisations – a platform for anyone with a phone. It’s getting hard for professional reporters to get a word in edgewise.

The burden is magnified by rising financial pressure on the news organisations that employ them, forced to compete for advertising revenue with the almost infinite resources of global platforms.

The cost of that economic disruption is still being tallied. As you will be aware if you’re seeing these words on paper, the old order is still with us and may yet survive the electronic invasion, because place and the physical world still matter to us. But there are no guarantees.

More important than the future of newspapers, however, is the future of journalism, the principal enabler of public discourse everywhere. Prospective journalists are now encouraged into tertiary education, but you can still become a fully-fledged professional without a degree or diploma.

That opens the door to mockery, even contempt, from the established university-endorsed professions of medicine, the law, engineering and the like. These elite professions are inclined to see “wordsmithing” as well down the pecking order, down there with politics and prostitution.

I think they’re right. Not in their contempt – journalism is as noble a calling as any – but in lumping reporters with politicians and sex workers.

Like those two venerable professions, journalism welcomes all-comers no matter what their formal education or social standing. The main prerequisites are a determination to do the job well and a willingness to learn from others.

Jacquie Lambie came to politics as a raw novice. Clive Palmer helped get her elected but this was essentially a self-made career. She drew on her own energy and inimitable wit, but also took others’ advice when it made sense. And she became an outstanding political representative.

So it is in the sex business, where there are no formal entry qualifications and success depends on putting your back into the job, so to speak, while winning and holding the support of patrons. And the same applies to journalism.

Journalism is about telling true stories, only some of which are stories people want to hear. You try to rise above the fray so that no-one is treated unfairly, and though objectivity is not quite the holy writ that it was when I started out, it remains something to strive for.

We admire people with heart – witness the love shown at Lambie’s farewell – and we want those who write about the affairs of the world to do so with passion. But we also want to be sure their passion is not obscuring other truths that we need to know.

Good reporters who find and write up our daily news honestly, fairly and independently are pure gold. More than ever, in a world bedevilled by fake news and spin, we need them to help us pick out the wheat from the chaff.

Last month Matt Brown, the ABC’s Middle East correspondent, talked about getting to the truth in the most fraught circumstances imaginable, the Syrian civil war, using the same technical marvels that give rise to fake posts, imprecise sources and Twitter outrage.

“While the tools of journalism are changing,” he said, “the rules have not. Scepticism and cross-referencing remain our only hope… you’ve got to be a bit old-school to make the new school worthwhile.”

The dazzle of new technology can blind us to what’s really happening. Truth doesn’t change with technology, and the best access to genuine news remains the people and organisations who have made it their job to record it – including the Mercury, for which I’m proud to write.

By the way, I confess I did moisten up slightly when I saw Lambie and Wong losing it on television. I must toughen up.