The Turnbull government is concealing massive policy failure

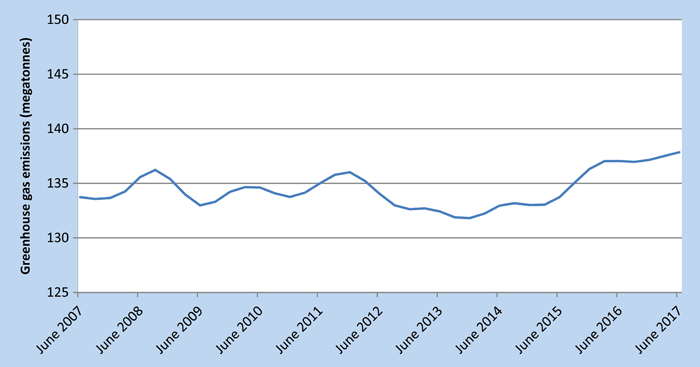

The National Greenhouse Gas Inventory’s trend line: June quarter emissions from 2007 to 2017. Figure 3 from “Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, June 2017”.

I’m seeing red this Christmas. It’s happened in years past, but now at the end of 2017 it’s deeper and darker than ever.

I don’t mean the red in shop windows or bus drivers in Santa hats, of which I thoroughly approve, nor the bright glow lighting up the dark of a northern winter as a huge wildfire eats into the outskirts of Los Angeles. (Whoever heard of such a thing?)

The red I’m seeing is caused by a malignant trend in public life: the wilful, calculated, planned use of the festive season to disguise government failure to meet its obligations.

In this case it’s about accounting for national carbon emissions as required under an international agreement to which we’re party, and the principal culprits are environment and energy minister Josh Frydenberg and prime minister Malcolm Turnbull.

I’d rather not keep coming back to this issue year after year, but it’s getting to me. Climate change is not just some trivial idea to be tossed aside at will. It’s real and it’s dangerous, and in failing to take their reporting obligations seriously the minister and his leader are seriously negligent.

This latest example of government misbehaviour also happened last year. By rights the pair should be made publicly accountable, and applying their own party’s law-and-order mantra about repeat offenders they should at the very least lose their jobs. Fat chance, I know.

The emissions data released before Christmas takes us up to June 2017, fully six months ago. The government has had all that time to put it out there for public and parliamentary scrutiny. But this matter of crucial importance was relegated to a footnote that got buried in the Christmas rush.

To understand why the official figures have been withheld for so long we need to set aside land use data, which since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol has repeatedly been used by successive Australian governments to make the picture look much rosier than it really is.

The government’s climate policy centrepiece, the Emissions Reduction Fund, has been focused mainly on land use, including tree growing and clearing. The problem with that is huge uncertainty around the data, making it impossible to measure the scheme’s effectiveness.

With fossil fuel use, which the ERF does not address, we know where we stand. The good news from the year to June was that our per-capita emissions were at their lowest for 28 years and the emissions intensity of the economy was nearly 60 per cent below its 1990 level.

But the really important figure is the actual amount of emissions, which in 2016-17 totalled 550.2 megatonnes. That is a rise of 0.7 per cent on the previous year, and continues a clear, steady rising trend since early 2014.

One of the messages from the June data is that electricity generation, while it remains the main source of emissions, showed marked improvement in 2016-17, an encouraging sign that new wind and solar power, despite the looming end of the renewable energy target, is having an impact.

But there are big concerns elsewhere. The Rudd and Gillard governments failed to incorporate petrol and diesel emissions in their carbon pricing schemes, and then the Abbott government made things worse by abolishing all carbon pricing.

In 2016-17, emissions from transport rose by 0.9 per cent and from non-electrical stationary energy by 3.3 per cent. These sectors’ combined emissions, mainly from burning petrol and diesel, now exceed those from electricity generation, yet both major parties continue to ignore them.

This troublesome issue will only get bigger while we fail to curb liquid fuel emissions. Bipartisan agreement seems the only way out, but in the absence of agreement on how, or whether, a price should be put on carbon, that looks out of the question.

The Turnbull government’s National Electricity Guarantee, which is being heavily promoted in the government’s climate policy review, does no more than shut the stable door after the horses have bolted. It will do little to cut electricity emissions and will not affect petrol and diesel use.

Expectations were low ahead of the release of the policy document this month, but even so it’s a big disappointment. Having set weak emission targets for 2020 and 2030, the government seeks to avoid heavy lifting by using foreign carbon credits while relaxing the obligations of business.

We have nothing to look forward to in 2018. Malcolm Turnbull may be a better policy salesman than Tony Abbott, but the awkward truth is that, just like his predecessor, while having no climate measures of any substance to offer he hoodwinks electors into thinking all is as it should be.

It isn’t. National climate policy is a shambles. Frydenberg’s attempts to hide emissions data show that he knows the figures are damning, yet he and his leader continue to play games with us.

We need an explanation, and they need to be called to account. They will be hoping the silly season erases all this from people’s memories. I hope and expect they’ll be proved wrong.