In 1831 a prominent English landscape artist took the extraordinary step, aged 63, of leaving his native land to live in Tasmania. He celebrated his new home in some memorable canvases, and today that home is being lovingly restored.

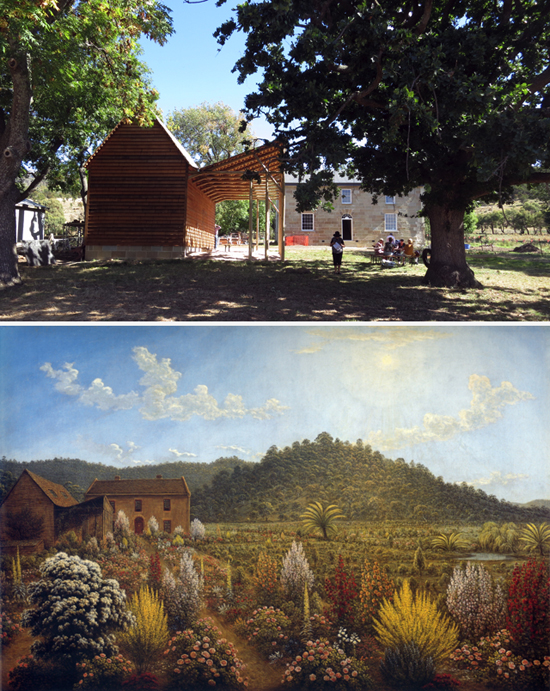

Patterdale today (top) and as Glover depicted it in 1834 (Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia).

From the colonial charm of Evandale, take the road south across the alluvial plains of the South Esk to Nile, then after another kilometre turn left at the Deddington Road.

Following the Nile River upstream, past Deddington and its handsome white chapel, you reach a fork in the road. Take the right-hand option, Uplands Road, and after a couple of kilometres you’ll come to clumps of European trees and glimpses of buildings among them.

Pull over, get out, breathe deeply and take in the views over Mills Plains and the Nile Valley to the north, and to the east across rolling hills to the ramparts of Ben Lomond. This is Patterdale, and you’re in Glover country.

John Glover is unique in our history. In 1830 he had decades behind him as a prominent English landscape painter, with French royal patronage, no less. But at the age of 63 he took a long, taxing sea voyage to the convict colony of Van Diemens Land to join his sons in a whole new life.

A few months in Hobart was all he needed to produce some memorable and now famous paintings of that young settlement and its spectacular setting, but John Glover grew up in country England and yearned for the life of a squire. He found it in a remote valley 40 km southeast of Launceston.

In his first years at Patterdale aboriginal people still moved through the landscape. He incorporated them into his painting, and was repelled by the actions of his neighbour, John Batman, who took government money to hunt them. Batman left the island in 1835 to help settle Port Philip.

I first learned about John Glover in the 1970s from John McPhee, then art curator for Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, and a Glover specialist. Others have since joined McPhee in rating Glover the greatest of early colonial Australian artists.

Glover’s Tasmanian paintings and notebook drawings are the work of a master in his field. They show a remarkable ability at his advanced age to set aside old European habits and embrace the very different visual qualities of his new land.

Today, Glover paintings are national treasures and sell for millions. In 2003-04 the artist was celebrated in an Australian touring show, and the Glover Prize, a significant annual cash award for paintings depicting the island landscape, kicked off in 2004.

Last year, at the urging of my good spouse, I had my first experience of the annual exhibition in Evandale of shortlisted Glover Prize entrants, and was blown away by the variety, technical skills and sheer creative vision on display.

That occasion was memorable for another reason. My Harvest Home, Glover’s canvas of a hay cart backlit by a late-afternoon sun, had long been a favourite of mine from when I worked at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Now there was the prospect of visiting the place of its birth.

A pamphlet offered the rare chance to see inside Glover’s home as a special “Ten Days on the Island” event. Patterdale was well-known as the subject of another iconic Glover canvas, A View of the Artist’s House and Garden, but how many had actually visited the place and entered its rooms?

Unlike nearby Clarendon House, Patterdale, named after a village in England’s Lakes District where Glover loved to work, is not what you’d call a grand colonial home. It’s well off the beaten track, a side road off a side road, and not well signposted. But the visit surpassed all expectations.

Glover’s home is being restored by current owners Carol and Rodney Westmore, who live on the adjacent Nile Farm, a couple of kilometres downstream. As far as records and the passage of time allow, they aim to have the property as close as possible to its appearance when Glover lived there.

This is a seriously ambitious undertaking. Though still a functioning farmhouse when the Westmores bought it in 2004, Patterdale was cold and crumbling – a shadow of the building depicted by Glover. Last year the task looked daunting, but what a difference a year has made.

Patterdale’s handsome front façade today may be smarter than it was originally, given the limited availability of quality sandstone and stoneworking skills in early-colonial rural Tasmania. But the exterior is now far closer to the original than the much-altered building the Westmores inherited.

Modifications are being made in back rooms to make Patterdale a viable bed-and-breakfast venue, but key elements of the original fabric are still visible. The restoration has been recorded in photographs, now displayed in a reconstructed studio close to the main farmhouse.

We can’t say whether the new studio is an exact replica of Glover’s “Exhibition Room” because little trace of the original remains. But we know the size is right because Glover’s son made a note of the building’s dimensions, and the close resemblance to the 1834 painted image is striking.

Most of John Glover’s best colonial works were painted on Patterdale farm, a point well understood by its owners who have identified the vantage points where the artist sat to paint or sketch. Visitors will be able to walk in Glover’s footsteps and see the same landforms that informed his painting.

A publicly-accessible Patterdale will add a new dimension to our understanding of Glover and his unrivalled contribution to Australian art. Carol and Rodney Westmore are doing us proud.