Experts, opinion leaders, politicians and the rest of us are in denial about Australia’s grossly inadequate climate response.

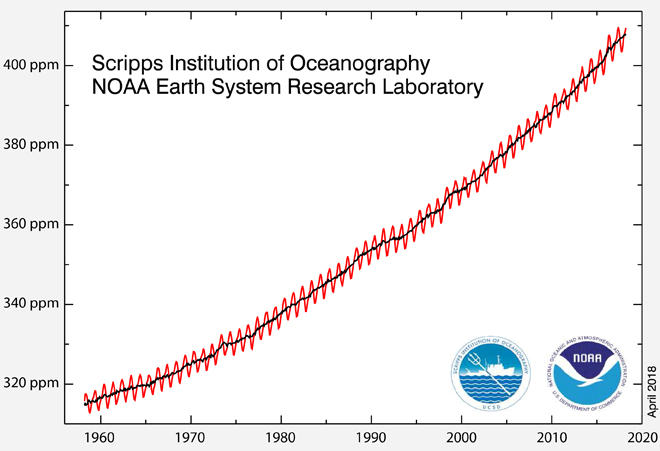

Atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, from 1958 to April 2018, in parts per million by volume (ppm). IMAGE: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Next time you hear a political leader talk about progress in curbing greenhouse emissions, bear this in mind: right now, the level of carbon dioxide in the global atmosphere is rising at a record rate.

Observations on Hawaii’s Mauna Loa show CO2 levels since 2010 rising at an average rate of 2.38 parts per million per year, well above the average annual rise of the previous decade, 2.04 ppm.

Carbon dioxide concentrations in the air are now at their highest level since the Pliocene, about three million years ago. Back then the world was about 2.5C warmer than today and sea levels were about 20 metres higher. That tells us a lot about where we’re heading now.

Australia and every other country that signed on to the 2015 Paris Agreement claim to be on track to meet their Paris targets. The atmospheric readings tell us another story altogether.

When a person rejects scientific evidence that humans are changing Earth’s climate, we call them a climate denier. Most political and business leaders are keen to let it be known they’re not in that category – they say they believe what science says and support measures to fix the problem.

We keep hearing from governments all over the world that measures are effective and targets are being met when CO2 readings show that this isn’t true, that measures are not working. Saying that all is well when it is not is a form of denial.

Australia can lower its emissions a little through better agricultural and forestry practices, but 80 per cent of our emissions are from burning fossil fuels: oil mainly for transport, gas for generating electricity, heating and industry, and coal for electricity and steel-making.

The only way to make an impact on emissions is to target fossil fuels, and our only scheme to do that was the carbon tax – inadequate because it didn’t tackle transport emissions, but much better than nothing. In 2014 the Coalition replaced it with the Emissions Reduction Fund.

The ERF pays for lowest-cost abatement projects out of existing revenue, without a supporting tax. Far from the economy-wide scheme it replaced, it focuses on land management and farming: avoided deforestation, soil carbon, savannah burning and methane from piggeries.

Working within very narrow limits, the ERF funds low-hanging fruit, involving feel-good actions that could offend no-one, like tree-planting and waste management. It has had no impact on the big emissions sources: coal-fired power, transport and industrial processes.

Environment minister Joel Frydenberg continues to tout the scheme as an outstanding success. After the most recent ERF auction in December he asserted that “the ERF is in stark contrast to Labor’s $15.4 billion carbon tax” which he said produced “little emissions reduction”.

But comparing the ERF with the carbon tax is comparing apples with oranges. The effectiveness of the carbon tax, which dealt directly with fossil-fuel emissions, was clear from generating and market data. Not so the ERF, whose emissions claims are all but unverifiable.

One of the principal objections to the ERF among those who have seriously studied it has been a lack of scrutiny of proposals to ensure they aren’t simply seeking government funding to do things, like leaving trees in the ground, that would have been done anyway.

Back in 2016, in the ERF’s early years, an environmental economist at the Australian National University, Paul Burke, expressed concern at the amount of money awarded to low-effort land projects – sometimes many times the value of the land concerned.

In February, University of Queensland senior economist Ian MacKenzie wrote in The Conversation that the “safeguard mechanism” intended to stop big business increasing its carbon emissions was not working because the government kept increasing emission baselines.

“This underlines the importance of having a climate policy that operates throughout the economy, rather than only in certain parts of it,” wrote MacKenzie. “If heavily polluting businesses can so readily be allowed to undo the work of others, this is a recipe for disaster.”

The Turnbull government’s state of denial about climate change was thrown into stark relief a fortnight ago when it announced a $500 million Great Barrier Reef restoration package which ignored the elephant in the room: a warming Coral Sea that has killed vast areas of coral.

Less obvious but just as dangerous is the shared fantasy in political, bureaucratic and business circles across the developed world, including Australia, that nations’ Paris pledges are somehow going to do the trick, when they are orders of magnitude less than what is needed to contain climate change.

Most leading economic advisers and commentators, while protesting their full support of national and international action to reduce emissions, continue to overlook climate factors when ruminating about future prospects. That crucial omission leaves a gaping hole in all their analyses.

As long as our governments continue pretending that they’ve done what’s necessary to address carbon emissions, and as long as leaders and pundits refuse to acknowledge the climate demon, looking every which way but squarely into its face, ours is a nation in denial.