Our inability to come to terms with some dark events in the history of European settlement diminishes us as a nation, and we need to deal with it.

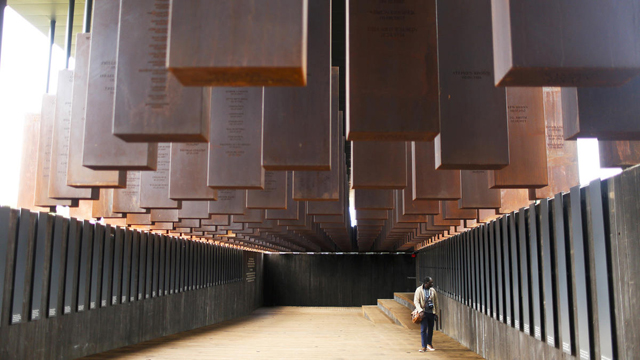

Inside the memorial to US lynching victims. PHOTO National Memorial for Peace and Justice

Two months ago a memorial dedicated to victims of white supremacy opened in Montgomery, Alabama, in the heart of America’s Deep South.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Memorial) and its accompanying Legacy Museum explore the confronting history of violence against black people since the Civil War officially ended slavery in that country.

The memorial is dedicated to the victims of lynch mobs, mainly in southern US states from 1877 to 1950, whereby local groups of white people took it on themselves to condemn and execute, and sometimes to torture and dismember, black people whom they believed had stepped out of line.

The monument’s principal feature is 805 steel boxes which hang above the heads of viewers. Each box represents a US county in which one or more of the over-4300 documented lynchings in the US occurred. The name of each victim is inscribed on the relevant county box.

The memorial, brainchild of a slave descendant, Bryan Stevenson, is a simple, moving statement about the experience of black people, former slaves and those coming after, who continued to endure crippling discrimination long after slavery was supposed to have ended.

Black people remain a disadvantaged minority in the US. They have a lower standard of health and a higher rate of alcohol and drug use than white counterparts, tend to be targeted by police, and suffer imprisonment at a rate vastly out of proportion to their total numbers.

A similar fate overtook indigenous North Americans: slaughtered, dispossessed of their land, deprived of its resources and shunted into reservations.

Does all that seem familiar? According to the Bureau of Statistics, indigenous Australians are far more likely to suffer unemployment, poor health, and drug and alcohol addiction than other Australians, and about 15 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-indigenous people.

Specifically excluded from the Federal Constitution, Aboriginals won voting rights in 1967, but that has made little difference to the way they are seen and treated. Governments still place them in a distinct category, separate from everyone else, and the rest of us prefer to think of other things.

So it was when European humans settled Australia 230 years ago. They took over this continent on the basis of a legal fiction called “terra nullius” – land belonging to nobody – which deemed the 800,000-odd dark-skinned beings who lived here to be nobody, another species, not human at all.

That absurdity survived because it made eliminating these unwanted people so much simpler. The leading scholar in this field, Henry Reynolds, has calculated that up to the 1920s the number of indigenous people killed approached 30,000.

Most of these deaths were not documented, but events around them were well enough recorded for us to know they happened everywhere that Europeans settled. The victims died without ceremony. To the killers these people were anonymous in life, irrelevant in death.

That, of course, was false. Each victim had a name and an identity, and each was important to someone, as sister, brother, father, mother, daughter, son, community member, leader. The victims were elders, breadwinners, carers and children: a people’s past, present and future.

The fact is, those who took over this country in 1788 had no knowledge of the society they set out to destroy. The bigger shame is that – at least until science revealed the richness, resilience and astonishing longevity of indigenous Australian culture – they never sought to know.

Mona has proposed a memorial on Hobart’s Macquarie Point to enable Tasmanians, in the words of Greg Lehman, to “respectfully mourn the outrages of our colonial past, and [celebrate] 400 centuries of Tasmanian history”. That surely deserves highly visible public recognition. But this is a national issue that merits a national response.

The War Memorial says Aboriginal deaths in defence of their land is not its responsibility. To its credit the National Gallery commemorates Aboriginal deaths in the frontier wars with an exhibit of 200 hollow log coffins from Arnhem Land. But this is not enough.

An inspired aspect of the US National Memorial is the way it approaches the question of local responsibility. An exact duplicate of each of the 805 county boxes has been made. Any US county can have the Memorial send it the relevant duplicate as a basis for a local lynching memorial.

The hidden war against Aboriginal people destroyed communities and desecrated sacred places. We need to acknowledge and identify those connections with place, as we do for our war dead, whose loyalty and loss in their nation’s name is honoured at local cenotaphs across Australia.

The seeds of racism lie deep within every individual and every society. It stems from everyone’s need for community and belonging, and fear of the other, the stranger from somewhere else. But this country of many races must find a way to rise above such base instincts.

Our nationhood is undermined and diminished by our failure to acknowledge the full story of our indigenous people. Confronting that past, bringing it into the light of day in the places where dark crimes were committed, would be a significant step toward reconciliation.