The disaster unfolding in Africa is one of many warnings about the need to think anew and plan for structural change. [16 August 2011 | Peter Boyer]

The Horn of Africa once experienced droughts every decade; now it has them every two years, reported the UN’s new Emergency Relief Coordinator, Valerie Amos, from Somalia last month. “We have to take the impact of climate change more seriously.”

The Horn of Africa once experienced droughts every decade; now it has them every two years, reported the UN’s new Emergency Relief Coordinator, Valerie Amos, from Somalia last month. “We have to take the impact of climate change more seriously.”

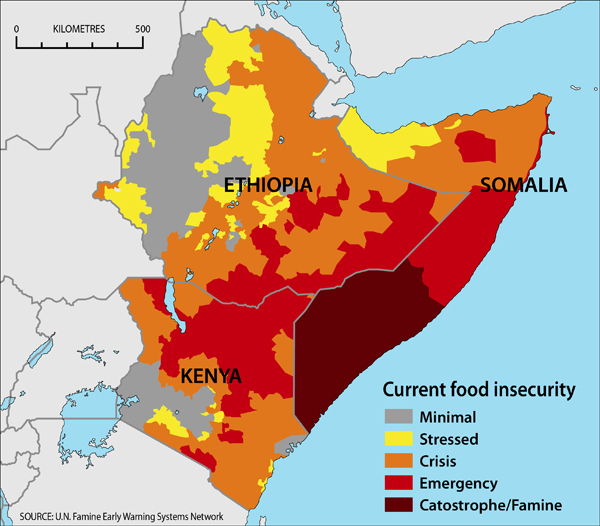

She may be right, though scientists say it probably won’t be clear for a decade or more how human-induced global warming figured in the drought now afflicting some 12 million people across Somalia, Ethiopa and Kenya.

It’s certainly true that this is the worst drought in at least 60 years — worse than conditions in the 1980s that led to a million deaths and prompted the Live-Aid appeal — and that with rains not due till October the resulting famine is shaping as the greatest catastrophe in modern history.

The creeping calamity in north-east Africa puts in perspective the economic distress of the global financial crisis, still alive and kicking after nearly four years. Millions of people are facing death by starvation and disease.

The African nightmare is just the worst of it. A deadly mix of climate disruption, economic dislocation and failing government seems to be forming into a global storm, with the one thing we can’t do without — food — at its epicentre.

People get stroppy when they’re hungry. A spike in bread prices caused by a 50 per cent rise in the world wheat price last year (in which Australian drought played a big part) was one of the triggers that brought angry people into the streets of North Africa and the Middle East last northern spring.

Food was once entirely a local affair, obtained from the village market or corner store. It has now become a global commodity, subject to the same kind of sharp fluctuations that we’re used to in share or currency trading.

That’s fine for the speculators, who thrive on big rises and falls, but it’s not much fun for the rest of the planet. Another food crisis in 2008 was resolved, temporarily as it turns out, by governments stepping in with subsidies, but that’s not an option in these straitened times.

Sudden shifts in the price of food don’t just destablise economies. Added to fluctuating energy and fuel prices (also subject to global commodity dealing), chronic poverty and extreme weather, they can have a profoundly unsettling effect on whole societies.

So here we are in a world where weather, food, poverty and general social unrest are all contributing to a rising sense of unease, a global crisis for which no-one has a solution and where governments struggle to bring a semblance of order to things that are beyond their control.

Whatever resolution is possible for this perfect storm, it won’t happen tomorrow, or even next year; perhaps not for decades. Many years of overheated economies, over-consumption of finite natural resources and over-reliance on technology and someone else (“them”) to fix things have robbed us of our resilience, leaving us exceptionally vulnerable to changing fortunes.

With demand for commodities, including food and oil, now well ahead of supply, prices continue to head skyward. That in turn has fed a growing thirst for fossil fuels — no matter how difficult the extraction process — in part to make fertiliser to grow crops for food.

While the world’s well-fed talk of sovereign debt and bear markets over a glass of wine, a seventh of the world’s population gets hungrier, their food diminishing with escalating prices, or their land becoming parched, degraded, or simply lost to an expanding city.

Oxfam has calculated that within 20 years basic food items could cost as much as 180 per cent more than today. That would be the end of the road for those at the bottom of the urban food chain. But it’s not all bad news — someone will make money out of a rising commodity price.

All the while the carbon keeps accumulating and our beleaguered, finite world keeps warming, while those politicians who aren’t fumbling with climate policy solutions are in a state of denial. Welcome to leadership in the 21st century.

The Horn of Africa figured prominently at the Hobart launch last week of “Grow”, Oxfam Australia’s food justice campaign. Aiming for a future where everyone has enough to eat, “Grow” seeks to transform the way we produce, consume and think about food.

It’s a far cry from drought-stricken Africa to Food Bowl Tasmania. But even putting aside the possibility of drought here, food security is a local as well as a global issue, as the state’s Social Inclusion Commissioner, David Adams, reminded the audience at the Oxfam launch.

High prices, limited variety, poor quality and lack of access to nutritional food result in “food deserts” in Tasmania, often in the midst of productive agricultural areas, said Prof Adams: “In a state designated as a food bowl, the bowl is often empty for many people in many places.”

Tasmania’s Food Security Council was set up in 2009 to support sustainable supply of nutritious, locally-produced food. Despite this, land for community food production continues to be overlooked in local planning decisions, and we still lack a designated minister for food security.

The present situation, both local and global, contains much to be concerned about, but fiddling at the edges of these problems while waiting for the axe to fall would be the height of folly. There’s much to be gained by keeping a clear head and actively preparing, both personally and collectively, for the structural shifts that must happen.

In the meantime, Africa needs our help. Oxfam is able to put your donation to immediate use, as are numerous other aid agencies. To find them just Google “East Africa donations”.