It’s a 500 to 1 bet that Australia’s summer of extremes really is caused by human-induced warming, says climatologist Will Steffen. [12 March 2013 | Peter Boyer]

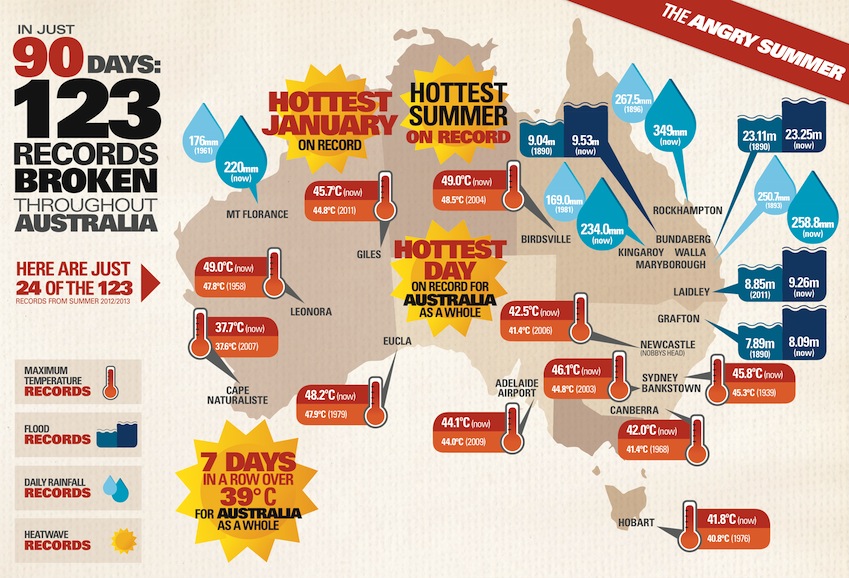

SOURCE: Australian Climate Commission, using data from Bureau of Meteorology

After an anxious week of smoke and ash from a wildfire threatening my bush neighbourhood last month, I finally found time for an overdue haircut.

“What a summer,” said my hair-trimmer. As I murmured agreement, she added, “one perfect day after another.”

Heat doesn’t turn me on as it does others, but I see where she’s coming from. If you like it hot and fires aren’t on your mind, days like we’ve been having in our little corner of the world must seem like paradise.

Scientists tread very delicately around current weather. Individual events, they say, can’t tell us much about climate, which deals with broad-scale trends over decades or centuries. Unusual seasons may be indicators, but are not in themselves strong evidence of a changing climate.

That reticence is shifting. “Australia’s Angry Summer shows that climate change is already adversely affecting Australians,” says a report published last week by the Climate Commission.

The lead author is the highly-credentialed Australian National University climatologist Prof. Will Steffen, who sees a clear pattern behind the record heat, rain and flood. The chance that natural variation caused all of the events, he says, is one in 500 — very risky odds to bet our future on.

“There is now an ongoing fundamental shift in the climate system,” Steffen’s report says, adding that the impact of the summer’s extreme weather on property, people and the environment highlights the serious consequences of an inadequate response to climate change.

Drawing on Bureau of Meteorology reports on heat and rain events from December to February, Steffen’s report points out that Australia’s “angry summer” saw 123 weather records broken across Australia. Among the highlights:

• On only 21 days in 102 years of national records has Australia’s average maximum temperature exceeded 39C. Eight of these days happened this summer, which was the hottest on record.

• The area-averaged Australian daily maximum temperature rose to 40.3C on January 7, breaking a record that had stood since 1972.

• January was Australia’s hottest month ever. Maximum records at 44 weather stations, including Hobart and Sydney, were broken. In Hobart’s case the temperature on January 4 (41.8C) broke the previous maximum by a full degree.

• Late in January Cyclone Oswald, taking an unusual track down the Queensland coast and well into NSW, broke January rainfall records for the Rockhampton-Bundaberg region and dumped 820 mm on Gladstone in four days — more than the city received in a year in either 2011 or 2012.

• Oswald’s rains brought record-breaking floods to the Burnett and Clarence rivers, causing major property damage and some loss of life in Bundaberg and Grafton. If we want to limit the severity of extreme events in the longer term, says the report, we have to take strong preventive actions during the present “critical decade”, including reducing our greenhouse gas emissions.

With the January fires behind us, you’d think that day upon day of windless, cloudless conditions would be a calming influence, but the later part of this summer (even in March we can’t say it’s ended) has left me unsettled, with a vague sense of unease, even threat.

It’s one thing to hear the stories appearing daily of big climate shifts elsewhere: of diminished Arctic ice, Arctic and Atlantic coastal inundation, of droughts and floods, lowered water tables and crop failures. It’s another thing to have such events happening so close to home.

For instance, what does this summer’s experience tell us about future food production in Australia? Australian Farm Institute director Mick Keogh sees huge challenges for farmers entering an era of even greater risk from fire, flood and drought.

Keogh warns farmers against pursuing high-return, high-risk activities, like abandoning mixed farming for pure crop production, without heeding climate trends. The danger is seen in stark relief in drought-stricken Western Australia, where wheat farmers are now walking off their properties.

Keogh argues that government should give its strong backing to a “multi-decadal” food production research effort to help farmers identify the best options for their properties. But there remains a clear disconnect between what nature is telling us and what power-brokers are talking about.

Both federal and Tasmanian elections are due within 12 months. Our summer of extremes is fresh in our memories and its links to climate change are confirmed by science, yet policies to mitigate the threat and plan for consequences barely rate a mention in the political debate.

We are all accountable for this failure, but especially our political leaders. While both Prime Minister Julia Gillard and Premier Lara Giddings have supported climate action in principle, their present inattention in the face of this massive crisis speaks volumes.

It’s no excuse that their opposite numbers rate climate policy even lower in the pecking order —if they think about it at all. Climate leadership demands that those with claims to the top job look further than the next election and deeper than party machinations.

Tasmania is not a bit player in the Australian debate on climate, nor is Australia insignificant in the global context. What our leaders say matters.

Climate policy is a huge challenge, touching on everything in our lives. It is also real and urgent. It is inconceivable that we should allow this election period to pass without giving it the priority attention it so clearly deserves.