Approval of the Carmichael project ignores the biggest impact of all [12 August 2014 | Peter Boyer]

Most people want to be seen by others as the genuine article, someone honest, reliable, what-you-see-is-what-you-get. But being human is complicated.

As long as we continue to have a social life, there’s always packaging involved. It might just be a change of clothes and a brush of the hair before going out, or something more elaborate and expensive, right up to plastic surgery, steroids, a complete body makeover.

Appearances drive how humans organise themselves. Schools and hospitals need to seem successful in meeting their obligations just as much as they need actual success. Business needs not just profitability but the appearance of it, which is why we hear so much about business confidence.

Substance is often peripheral in politics, but appearance is always front and centre. All democratic leaders must be accepted by the people they claim to lead if they’re to survive. Every political action and statement is motivated by the need to appear strong, capable and in charge.

In the biggest public or private organisations, maintaining the appearance of being in control is an industry in itself with a life of its own, where leaders employ people, sometimes whole armies of them, to develop and maintain a massive and complex mythology.

I know a bit about this. In a past life I was an information manager, the sort of title given to people paid to ensure the body corporate always looks competent and in control of its destiny.

In those inevitable times when my organisation made a mistake and definitely wasn’t controlling its destiny, I sought to avoid having to lie, but I knew this was in itself a kind of lie. I felt uncomfortable but I did it, because my job was to keep up appearances.

So it goes across much of government, business and society in general. Deception and delusion are so much part of life in our market-dominated world that we often struggle to tell fake from real.

Swimming against this tide is science, whose sole purpose is to penetrate outer appearances to find real inner nature. Today, when everyone is used to fudging things, science is confronting us with the reality that things we’ve taken for granted have to change, rapidly and decisively.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the International Energy Agency have separately concluded that the planet will heat to a dangerous level unless we leave at least two-thirds of all presently-known coal, oil and gas reserves in the ground.

The Abbott government and its business supporters treat this expert advice from the world’s peak climate and energy bodies not as a challenge from science to be addressed but an empty leftist threat to be ignored. If that isn’t culpable negligence, I don’t know what is.

Environment minister Greg Hunt never neglects to tell us that he takes climate change seriously. Last month he approved a Queensland coal mining project, Australia’s largest-ever, subject to “the absolute strictest of conditions”, as he put it.

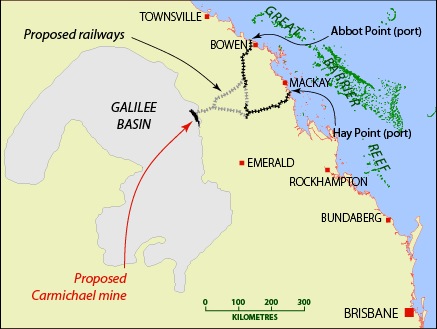

Those conditions, Hunt said, would ensure that the Carmichael mine, inland from Mackay, will have a net zero impact, with all negative effects avoided, mitigated or offset. But he left out completely the mine’s most devastating impact, on atmospheric carbon levels.

Hunt can claim a precedent. When Labor minister Tony Burke approved the Whitehaven mine at Maules Creek, NSW, last year he ignored the fact that burning the coal from there will emit about 30 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, the same as New Zealand’s total emissions.

Whitehaven faces continuing local anger over what coal-mining is doing to biodiversity, water and landscape in the Upper Hunter Valley, just as Carmichael coal has attracted ire for the threat to the Great Barrier Reef posed by shipping it out. But the climate impact has slipped under the radar.

Location of Galilee Basin, Carmichael mining lease, and proposed railway and port facilities. MAP BY SOUTHWIND

When Carmichael coal is exported to India and burned, it will release 100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year for the mine’s lifetime of more than half a century. This is about a fifth of Australia’s annual total from all sources, way beyond any single enterprise in our history.

In an illuminating moment during discussion of the Carmichael decision on The Bolt Report last week Andrew Bolt, not known for his support of the science of human-induced warming, asked Hunt point-blank, “Won’t this, by your own calculations, mean hot days get hotter?”

Hunt responded that climate was a global responsibility – “no one country can do it alone” – adding “we have to bring people out of poverty.” The Carmichael mine, he said, “is about providing electricity to up to 100 million people in India”.

He wants us to believe that an altruistic Abbott government supports the Carmichael mine because coal power will always be cheap (not a safe assumption) and because it wants poor Indians to have a chance in life. Whoever believes that will believe anything.

Pressed by Bolt, he argued that the Carmichael decision represented a “balance”, “not extreme left or right”. His choice of words might have come from another anti-abatement line, that with every scientific statement supporting global warming there must always be a contrary one, for balance.

It’s all about appearances. Greg Hunt’s job isn’t to look after the environment, but to lend a veneer of environmental credibility, however thin, to a government that wants our coal resources exploited to the maximum extent possible while there’s still someone prepared to pay for them.

One day, probably decades too late, everyone in the world will be able to see the damage we did for those pathetic thirty pieces of silver.