It’s time we stopped patriotic posturing by globe-trotting politicians and returned Anzac Day to its community roots.

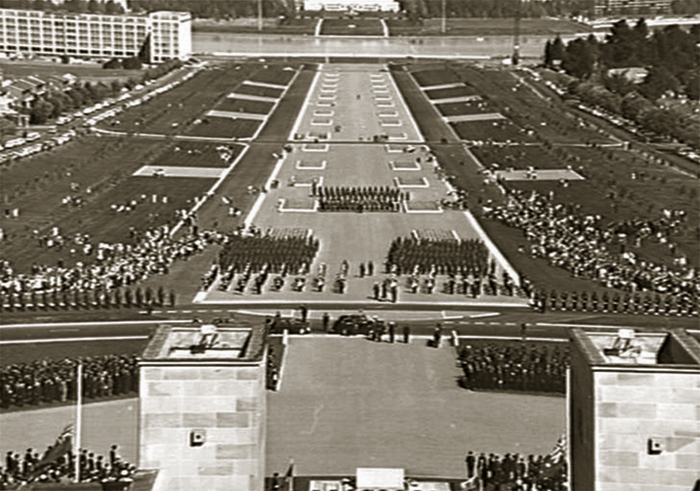

Fifty years on: How we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings in 1965. PHOTO Australian War Memorial

Another Anzac Day is almost upon us, with its reminders of ultimate sacrifices on Gallipoli beaches and Flanders fields, and choruses of “we will remember them” and “lest we forget”.

Setting aside the mild irony about our use of these words, taken from patriotic poems written not for Australia but for Mother England, Anzac Day is a serious business. For many Australians, remembering our war dead each April 25 is a solemn and deeply personal matter.

About 60,000 young Australians were killed in four horrific years from 1914 to 1918, equivalent to over 300,000 today as a proportion of the national population. A far greater number were wounded, and an incalculable but undoubtedly huge number of young men came back traumatised.

That enormous casualty count had a devastating impact on lives back home. Farms, towns, regions – the whole country – were deprived of fathers, brothers and sons, stretching human resources to their limit and placing a near-intolerable burden on our women.

We need to acknowledge this, as we need to recognise war anywhere and at any time as a scourge. The best Anzac Day speeches, such as that of the late Tasmanian governor Peter Underwood in 2014, remind us of this undeniable truth.

The solemnity of Anzac Day was what Alan Seymour set out to get across in The One Day of the Year, a play first performed in 1960 looking at how Australians view our big day.

The play’s depiction of drunk veterans was said to show disrespect for the Anzac tradition. Seymour and the theatre companies brave enough to put it on had to endure a bomb threat in Sydney, and in Adelaide to have a police guard at the theatre door.

Opponents missed the point of the play. Far from attacking veterans, it recognises their sacrifices and evokes compassion for them and their families. But it does shine a spotlight on the futility of war and the complexity of our national response to it.

As a boy scout around that time, I marched on one or two occasions with the veterans in our town’s Anzac Day street parade. I had heard stories from an elderly uncle about trench life in France, but they were for a child’s ears. I learned nothing of its horrors.

For me at that time, Anzac Day was a simple affair – a very local event around our town’s cenotaph, in which politicians kept a low profile.

You get the same sense of simplicity from the typewritten list issued by then-prime minister Robert Menzies to mark the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings in 1965 – a landmark Anzac Day by any measure.

Menzies’ program simply listed the main capital city events along with an MP or senator to represent the federal government at each, including a service at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra attended by Menzies himself.

There’s nothing to show whether Menzies made a speech; the website for official prime ministerial statements and speeches has no such record. It’s perfectly possible that he simply laid a wreath, which would fit with my own recollection of Anzac Day in those times.

Except for the odd address to troops on service, prime ministerial speeches at Anzac Day events were almost unheard of until 1990, when Bob Hawke travelled to Gallipoli to mark the 75th anniversary of the Anzac landings there.

That was also the first time a prime minister marked Anzac Day in a foreign land. Two years later, a recently-installed Paul Keating repeated the exercise in Port Moresby, in keeping with Keating’s preferred emphasis on the 1941-45 defence of Australia. He gave no other Anzac Day speeches.

Such restraint went out the window under John Howard. He delivered an Anzac Day speech for all but two of his 12 years as prime minister, mostly in Australia. He also gave Anzac Day speeches in Thailand in 1998, Iraq in 2004 and Gallipoli in 2000 and 2005.

Kevin Rudd gave two long Anzac Day speeches, in 2008 and 2010, both domestic. Julia Gillard spoke in Seoul in 2011 and Tony Abbott at Gallipoli for the 100th anniversary event in 2015.

Whatever else it represents, Anzac Day is now a televised platform for politicians who want to look like a leader. Tonight this will reach a zenith when prime minister Malcolm Turnbull opens the $100 million Sir John Monash Centre near Villers-Bretonneux in France.

As the multi-year centennial extravaganza winds down, we need to ask ourselves, where is all this heading? Other countries lost millions of soldiers on the Western Front, many times more than we did, but Australia alone invests this sort of money in national memorials there.

I feel uneasy about the way our Anzac traditions have been politicised and exported. I vote we refocus our attention back home, back where all this began in our local high streets and cenotaphs. And at our watering holes, with pokies ditched in favour of two-up games. Regulated, of course.