The Hodgman government should take some credit, but doing the same for zero net emissions is a step too far.

South Bruny from the Neck. PHOTO Discover Tasmania

Slowly – too slowly – the ruckus over coal-fired electricity is dying as Australians come to see what renewable power coupled with advanced information technology can achieve.

We understood such a possibility here in Tasmania once, when we had a fully-renewable power grid. That ended when the 1967 drought led us to supplement hydro with fossil fuels – oil and gas.

For the past 12 years – minus the months it’s been inoperative, including now – we’ve also had Basslink, touted by government as a means of selling clean hydro energy interstate but used more often to import brown coal power from Victoria.

Even on this island, having lived with hydro for over a century, we’ve been subjected to the false notion that without thermal power stations we’re doomed, and that big blackouts have been caused entirely by not enough coal-fired power to fill the gaps left by intermittent wind and solar.

This is a political line, not shared by professionals in the power business, who know there are many ways of dealing with the fact that wind and sunshine are not a continuous resource. One indicator of how this might play out comes from an island community in south-east Tasmania.

The Bruny Island battery trial, led by the Australian National University’s College of Engineering and Computer Science, involves a network administrator (TasNetworks), teams from the universities of Sydney and Tasmania and a Canberra software business called Reposit Power.

At the end of a single power supply cable from mainland Tasmania, Bruny Islanders suffer more than most from blackouts. This was a logical choice for a trial seeking to know how a community could benefit from local generation and battery storage managed by a smart network.

With $2.9 million in funding from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), the consortium began its work in 2016 by installing household solar and battery storage systems in 40 Bruny Island homes.

But it’s how these systems are managed that sets this scheme apart. ANU scientists have developed a technology they call Network Aware Coordination, or NAC, which allows the Bruny homes’ solar-battery systems to work seamlessly with the electricity grid to help manage electricity supplies at times of peak demand.

The Bruny trial has shown what can be achieved with a higher level of distributed generation – household solar and computer-controlled storage – to make the grid both more efficient and more reliable.

Sociological and psychological data gathered by the other universities in the group helped fine-tune the NAC technology to allow each customer to easily discover what was happening to the energy their homes produced and how they could get maximum financial return from the network.

The NAC is tailor-made for distributed generation. Its algorithm can deal with demands of any scale, from individual homes to all of Australia if needed, while still retaining ease of use and complete privacy for each customer.

Batteries represent a new paradigm for the National Electricity Market, which so far does not have arrangements in place to fully utilise the responsiveness of battery power. The market’s regulatory framework has to be updated before it can accommodate the likes of the NAC.

When that happens, and when the Bruny Island technology or a future iteration of it is rolled out more widely to take advantage of existing and new household storage, the potential of intelligent network management and a truly distributed power network will begin to be realised.

The scheme’s potential to deliver huge long-term benefits Australia-wide, including lower network costs and power prices, were recognised a few weeks ago when it was named the 2018 Australian Energy Project of the Year by the Electrical Energy Society of Australia.

Tasmania should take pride in the Bruny success just as it should be proud of its hydro network, which with the potential of pumped hydro using solar and wind power has given us a huge head-start over the rest of the country in minimising carbon emissions.

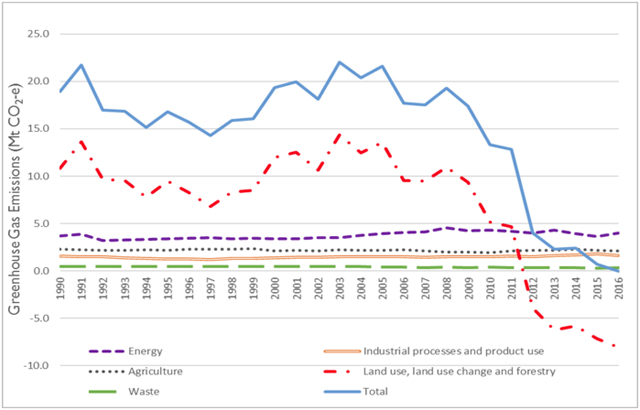

The Hodgman government should share in that pride. But its boast last week to have led Tasmania to achieve zero net greenhouse gas emissions in 2015-16 – 35 years ahead of its 2050 target – demands an explanation.

Figure from Tasmanian Greenhouse Gas Accounts Report 2015-16: Tasmania’s greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1989-90 to 2015-16

I’ve said before that a government intent on effective climate action would seek to cut fossil-fuel emissions and severely limit land clearing, and wouldn’t even contemplate native forest logging.

The world leadership claim rests on a logging industry downturn and the success of the 2012 Forest Agreement – which the government seeks to expunge from history – and to a lesser extent on not having to include emissions from imported brown coal power, which go on to Victoria’s books.

I’ll add my congratulations to the Hodgman government when it finds the courage to ban logging in native forests and gives these priceless carbon stores the protection of permanent reservation.