A string of calamitous weather events and our rising carbon emissions leave a sense of foreboding for the year to come.

Celebrating is what we do in the festive season, but it’s hard to feel good about the truly grotesque year we’ve just had, nor about the one that’s to come.

Underlying our unease is a clearly changing global climate. Governments now know there is no legitimate counter to the fact that this is caused by atmospheric pollution, supported as it is by tens of thousands of scientific studies and by all the world’s major scientific institutions.

Science is discovering some disconcerting trends in extreme weather, including more very heavy rainfall events, more intense, longer-lasting heatwaves, more severe fire outbreaks and more dry-lightning storms.

Reflecting this, public concern over exceptional weather events and political responses (or their absence) has grown steadily, to the point of undisguised alarm in some quarters, such as communities on low-lying islands. In 2018, triggers for that concern piled one on top of another.

In the Arctic over a few days last February, when the region is normally at its coldest, temperatures reached 20C above average. Sea ice began to disappear, and in northern Greenland the period of time above freezing on those days was more than three times the year-round average.

Out-of-season fires in Queensland and NSW prompted some local authorities to open the annual bushfire danger season in August – earlier than ever before. In November, a record-breaking hot spell in tropical Queensland fuelled fires of unprecedented severity.

Meanwhile, extreme summer heat across northern countries sparked many large wildfires including a blaze in Greece that killed 100 people and Scandinavian outbreaks north of the Arctic Circle.

California had its worst-ever summer fire season in July and August. Then in November yet more devastating fires obliterated a town called Paradise in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, killing 85 people.

Major flash flooding events, too numerous to list here, occurred about every two days through 2018. Most involved multiple lives lost and all of them drove people from homes, at incalculable emotional cost and billions in property damage.

Science has affirmed climate links in a multitude of droughts, heatwaves, wildfires, storms and floods over recent years, with ominous implications for humanity, including food shortages, disease, income loss, warfare and forced migration.

A global survey of flooding events published in October by Nature Communications found a rising trend in the incidence of extreme flash floods, markedly higher than indicated by models and well beyond the capacity of existing infrastructure to cope.

The premier climate science authority, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, reported two months ago that the world has about 12 years to get carbon emissions declining steeply enough to offer reasonable hope of avoiding dangerous climate change.

The IPCC report, requested under the Paris Agreement of 2015, called for coal power to be phased out and transport, energy and industrial systems to be radically transformed by mid-century, a global effort with “no documented historic precedent”.

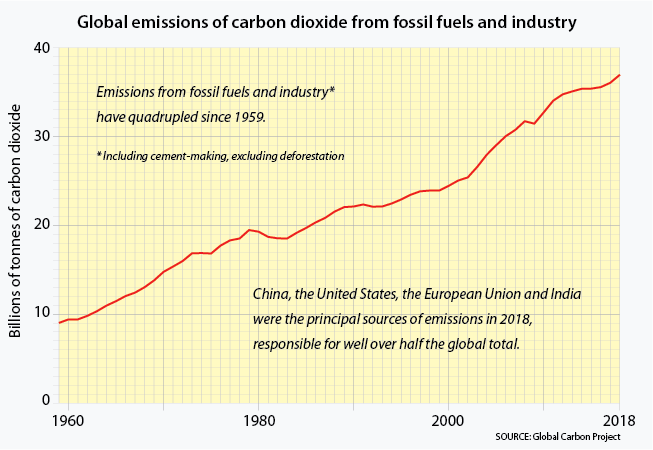

Current emission trends indicate we’re not about to break that mould. After a brief levelling off in 2014-16, global emissions rose by 1.6 per cent in 2017. In 2018 emissions are expected to rise 2.5 per cent, to a record 37 billion tonnes.

Hugh Saddler’s National Energy Emissions Audit revealed just before Christmas that Australian emissions have been rising steadily for four years, including 2018. Lower electricity emissions have been more than offset by rises in transport and stationary energy.

All this is feeding into public disquiet about government’s response to the clear and embarrassing evidence that climate policies are failing. In our own federal election this year we can expect climate change to figure more prominently than ever before.

As things stand, this can only benefit Labor, whose emissions policies – modest at best when set against the IPCC findings – are streets ahead of what is presently on offer from Scott Morrison.

Yet South Australia has shown that it doesn’t have to be this way. Steven Marshall’s Liberals took power from Labor in March, and despite a contrary stance in the election campaign the new government has taken on its predecessor’s role as a champion of clean energy.

The previous government’s renewable target of 75 per cent by 2025, attacked in Canberra as being too ambitious, is being exceeded by a wide margin. The Australian Energy Market Operator now calculates that the state could achieve 100 per cent renewable energy by then.

Informed by this and by voters’ clear preferences, Marshall’s team knows its electoral future rests heavily on strong support for renewables. It understands what its federal counterparts cannot – that conservatism and renewable energy can happily coexist.

The struggle to contain emissions has lost many good years because politicians could not admit they were wrong. But South Australia is showing us that change can happen quickly. Getting this experience onto a national stage can’t come soon enough.